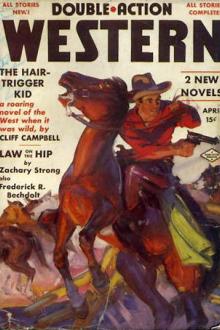

The Hair-Trigger Kid by Max Brand (best sci fi novels of all time TXT) 📕

"The curtain ain't up," said the sheriff, "but I reckon that the stage is set and that they's gunna be an entrance pretty pronto."

"Here's somebody coming," said Georgia, gesturing toward the farther end of the street.

"Yeah," said the sheriff, "but he's comin' too slow to mean anything."

"Slow and earnest wins the race," said another.

They were growing impatient; like a crowd at a bullfight, when the entrance of the matador is delayed too long.

"We're wasting the day," said Milman to his family. "That's a long ride ahead of us."

"Don't go now," said Georgia. "I've got a tingle in my finger tips that says something is going to happen."

Other voices were rising, jesting, laughing, when some one called out something at the farther end of the veranda, and instantly there was a wave of silence that spread upon them all.

"What is it?" whispered Milman to the sheriff.

"Shut up!" said the sheriff. "They say th

Read free book «The Hair-Trigger Kid by Max Brand (best sci fi novels of all time TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Max Brand

- Performer: -

Read book online «The Hair-Trigger Kid by Max Brand (best sci fi novels of all time TXT) 📕». Author - Max Brand

fear. For the man, whatever his other faults of greed, low cunning, and

knavery, was brave, and had demonstrated his courage over and over again.

Yet here he had fled into his house, barricaded the door, locked the

lower windows, and now was signaling—no doubt frantically—in an appeal

for help!

The possible mob was the only solution that appeared to the mind of the

sheriff. He loosened his Colt in its holster and set his mind sternly on

the work that might be preparing for him. No matter what he thought of

Shay, mob violence was something which he had put down in Dry Creek, and

he was prepared to put it down again at whatever risk.

In order to get closer to the scene of action, as soon as the mirror at

the dormer window stopped signaling and the window itself was closed with

a violent bang, he went downstairs, and in the lobby found his friend,

the rancher, with his wife and daughter beside him, looking as happy as

any child.

Even with the trouble that was now in his mind, the sheriff could not

help letting his eye linger pleasantly on the trio for a moment.

“Clean-bred ones,” said the sheriff to himself, and being a man his

glance lingered longest on the face of Georgia Milman. She was as brown

as an Indian; she had the rounded, supple body of an Indian maiden, also,

and Indian black was her hair, but her eyes were the blue which one sees

in Ireland. She swung her quirt and greeted the sheriff noisily and

heartily. They had shot elk together the season before.

“Father says that there’s some sort of trouble brewing in the Shay

house,” said she.

“I dunno,” answered Lew Walters, “but they’s trouble bud-din’ and

bloomin’ over there. Come out on the veranda and have a look at the

fireworks. Hello, Mrs. Milman. This here man of yours, he sure needed

tyin’ before he seen you down the street. Are you-all comin’ out on the

observation platform?”

They were. And the rest of the town seemed to be heading in the same

direction, so swiftly had the rumor of excitement spread.

It was not malicious curiosity that brought the crowd. It was the same

impulse which draws men together to see a prize fight. There were perhaps

fifty people already on the long covered veranda that ran in front of the

hotel, supported by narrow wooden pillars, with a row of watering troughs

on each side of the steps where a twelve-horse team could be watered at

one time without unharnessing them.

“You’re gettin’ a new brand of trouble here in Dry Creek, sheriff,” said

an acquaintance.

“I’ve seen a lot of brands,” said the sheriff. “What’s the new one gunna

be like?”

“The Kid is comin’ to town, I’ve heard. Charlie Payson, he passed the

word along.”

“Which is this Kid?” asked Milman. “Denver, Mississippi, Chicago, Boston

or—”

“This ain’t any of them. It’s the Kid,” replied the sheriff. “You mean to

tell me that Charlie Payson is handin’ out that story? What would the Kid

be comin’ to Dry Creek for?”

“Yeah,” said the other, “you’d say that Dry Creek wouldn’t give him no

elbow room, hardly. But that’s what Payson is sayin’. I dunno how he

knows. Unless’n maybe he got a letter. Some say that he was with the Kid

down in Yucatan once.”

“I’ve heard that story,” said the sheriff. “How they went up the river

and found the old temple and got the emerald eye, and all that. Is they

anything in that yarn?”

“They’s likely to be something in any yarn about the Kid.”

“Who is the Kid?” said Elinore Milman.

“You never heard of him?” asked the sheriff.

“No. Never. Not of a man who went by just that nickname. What’s his real

name?”

“Why, that I dunno. But betwixt Yucatan and about twenty-five hundred

miles north they is only one Kid, so far as I know.”

“What sort of a creature is he? Young?”

“The sort of creature he is,” said the sheriff, “is a hard creature to

describe. Yes, mostly he’s young.”

“What do you mean by mostly?”

“Well, some ways they ain’t nobody no older in the world. Maybe I can

give you an idea of the Kid by what a feller told me he seen in a Mexican

town in Chihuahua. When the word came in that the Kid had been sighted

around those parts, they fetched in a section of the toughest rurales

they could find, and they swore in a flock of extra deputies, and them

gents that had extra-fine hosses. They led ‘em out of town and sneaked

for the tall timber, and the women that had pretty daughters, they got

‘em indoors and turned the lock over ‘em, and sat down in front of the

doors with the biggest butcher knives that they could sharpen upon the

grindstone. And the gamblin’ house, it closed up and cached all of its

workin’ money by buryin’ it real secret in the ground, and the big store,

it closed and locked up all of its windows. It looked like that there

town had gone to sleep. But it was lyin’ wide awake behind its shutters,

like a cat. Well, down there in Mexico, they know the Kid a lot better

than we do, and that’s the way they treat him there.”

“But here in Dry Creek,” Elinore Milman questioned, “you don’t take all

those precautions when this philandering horse thief, gunman and yegg

comes to town?”

“Ma’am,” said the sheriff, “you’ve heard that he’s comin’. And ain’t you

standing out here with Georgia right beside you?”

She flushed a little, but the girl merely laughed.

“I imagine that I can venture Georgia,” said the rancher’s wife.

“Yeah,” said the sheriff, “I see that you do. But if she was mine, I’d

blindfold her and put her in a cyclone cellar when they was a chance of

that Kid comin’ by. Up here, on this side of the Rio Grande, we’re all

too dog-gone proud to be careful and that’s the cause of a terrible lot

of broken safes and necks and hearts!”

There was a distinct strain of seriousness in this speech, but Mrs.

Milman, turning toward her daughter, smiled a little, and Georgia smiled

in turn. They were old and understanding companions.

Murmurs, in the meantime, passed up and down the veranda. “What’s it all

about, sheriff?” asked several men from time to time.

He merely shrugged his shoulders and continued to stare at the house

opposite him, as though he were striving to read a human mind.

“The curtain ain’t up,” said the sheriff, “but I reckon that the stage is

set and that they’s gunna be an entrance pretty pronto.”

“Here’s somebody coming,” said Georgia, gesturing toward the farther end

of the street.

“Yeah,” said the sheriff, “but he’s comin’ too slow to mean anything.”

“Slow and earnest wins the race,” said another.

They were growing impatient; like a crowd at a bullfight, when the

entrance of the matador is delayed too long.

“We’re wasting the day,” said Milman to his family. “That’s a long ride

ahead of us.”

“Don’t go now,” said Georgia. “I’ve got a tingle in my finger tips that

says something is going to happen.”

Other voices were rising, jesting, laughing, when some one called out

something at the farther end of the veranda, and instantly there was a

wave of silence that spread upon them all.

“What is it?” whispered Milman to the sheriff.

“Shut up!” said the sheriff. “They say that it’s the Kid!”

He came suddenly into view, as a puff of wind cuffed the dust aside. His

back was so straight and his stirrup so long that he seemed to be

standing in his saddle. His bead was high, and his glance was on the

distance, like one who knows that his horse will pay heed to the

footwork. But there was nothing unusual in his get-up except for the

tinkling of a pair of little golden bells which he wore in his spurs.

Such a silence had come over the crowd on the veranda that this sound,

small as the chiming of a distant brook, grew distinctly audible. The

sheriff suddenly nudged Georgia.

“There’s a horse for you,” said he. “That’s the Duck Hawk, as they call

it. That’s the mustang mare that he caught in Sonora. Ain’t she the

tiptoe beauty for you?”

She came like a dancer, daintily but smoothly, with a pride about her

head, as though she felt she were carrying some one of vast distinction.

A king would have liked to ride on such a horse; or a general, or any

mayor in the world, to lead a procession.

“She gets her name from her markings,” explained the sheriff. “You see

the black of her all over, except the breast and the belly is white. I

never seen such queer markings on a hoss before. But that’s the Duck

Hawk. I seen her out of Phoenix once. I’d dig potatoes for ten years for

a hoss like that, honey. How long,” he added, “would you dig ‘em for such

a man?”

He turned with a grin as he spoke, and the girl smiled back at him.

“He looks all wool,” she said most frankly.

So he did. The sort of wool that wears in the West, or on any frontier.

Now, as he came up to the hotel and jumped out of the saddle, they could

see that he had the strong man’s shoulders, smoothly made and thick; and

the legs of a runner such as one finds among the straight-built Navajoes.

He had the deep desert tan, but his eyes were of that same Irish blue

which made men look at Georgia Milman with a leap of the heart.

Their hearts did not leap when they stared at the Kid, however. Instead,

glances were apt to sink to the ground.

The Kid took a bit of clean linen from his saddle bag and wiped the

muzzle of the mare before he permitted her to drink, which she did freely

but daintily, for Georgia Milman could see, now, that there was no bit

between her teeth.

“Hello, folks,” said the Kid. “Waiting here for a procession to come

along, or is somebody going to make a speech?”

He picked out faces, here and there, and waved to them, but when he saw

the sheriff he jumped lightly to the edge of the veranda between two of

the troughs. The intervening people slipped hastily back, like dogs,

Georgia thought, when the wolf steps near.

The Kid took the sheriff’s hand in a warm grip.

“I’m glad to see you, Walters,” said he. “I thought I’d drop in here at

Dry Creek to see you. You’ve made my old friend Shay so much at home that

I thought you might want me up here too.”

“I’m glad to see you, too,” said the sheriff instantly. “I’ve got a right

good little of jail over yonder, Kid, and you’ll find it mighty cheap

here in Dry Creek to get a ticket to it.”

“Never buy anything but round trips,” said the Kid, “and I hear that

yours is only a one-way line. You’re not introducing me to your daughter,

Walters?”

“This is the yegg I was telling you about, Georgia,” said the sheriff.

“This is the same sashayin’ young trouble raiser. The lady’s name is

Milman, Kid.”

Comments (0)