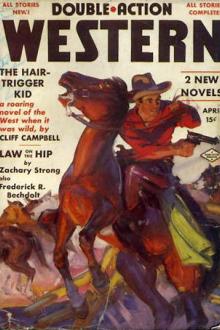

The Hair-Trigger Kid by Max Brand (best sci fi novels of all time TXT) 📕

"The curtain ain't up," said the sheriff, "but I reckon that the stage is set and that they's gunna be an entrance pretty pronto."

"Here's somebody coming," said Georgia, gesturing toward the farther end of the street.

"Yeah," said the sheriff, "but he's comin' too slow to mean anything."

"Slow and earnest wins the race," said another.

They were growing impatient; like a crowd at a bullfight, when the entrance of the matador is delayed too long.

"We're wasting the day," said Milman to his family. "That's a long ride ahead of us."

"Don't go now," said Georgia. "I've got a tingle in my finger tips that says something is going to happen."

Other voices were rising, jesting, laughing, when some one called out something at the farther end of the veranda, and instantly there was a wave of silence that spread upon them all.

"What is it?" whispered Milman to the sheriff.

"Shut up!" said the sheriff. "They say th

Read free book «The Hair-Trigger Kid by Max Brand (best sci fi novels of all time TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Max Brand

- Performer: -

Read book online «The Hair-Trigger Kid by Max Brand (best sci fi novels of all time TXT) 📕». Author - Max Brand

The girl flushed and bit her lip. “Do go on,” said she.

“We moved off the old land—there was nothing but a small shack on

it—and then we started across the hills for a sort of promised land

about which we’d heard a lot. We plugged along at a good rate. There was

no hurry. We wanted to have our cattle in good condition when we came to

the badlands, where we’d heard that the grass had been burned out, and

that it was very hard to push through. So we slogged along very slowly,

and enjoyed being on the road. Our first bad luck was a real smasher.

Half a dozen rustlers came down on us one evening, and scooped up

everything that we had in the way livestock, except for the two milk

cows. They took the horses, the mule, the burro, even; and the steers.”

“The scoundrels!” said the girl. “The contemptible scoundrels! Did you

ever learn who they were?”

“There were five of them,” said the Kid dreamily, as though he were

looking across the years and seeing that evening closely again. “Yes, I

learned all of their names. A tough bunch. Very tough. I learned all of

their names, however.”

“How? But go on! What did you do, then?”

“My father was a hard man,” said the Kid. “He’d lived a hard life. He had

the pain of work in his eyes, if you know what I mean,”

“Yes,” she answered. “Of course I know.”

“He’d been a farmer. And a scholar! But a farmer—frosty mornings,

chilblains at nights, freezing behind the plow, roasting in the hayfield.

He worked like a dog.

“Well, when we lost our stock, we were on the edge of the desert. My

mother begged him to turn back, but he wouldn’t do it. He wouldn’t go

back to the old life. He lightened the wagon of everything that we didn’t

absolutely need, and then he yoked up those two milk cows—and we went

ahead!”

“Great heavens!” said the girl. “Across the desert? With cows!”

He paused. His face, losing its characteristic smile, became like iron.

“My mother was a very young woman to have had a boy of six. She was a

jolly sort. She was straight, and had a good, sun-browned skin and her

eyes were always laughing. Like a dog that loves all the people all

around him. You know?”

She nodded She felt a breathless interest.

“She was rather tall,” said the Kid, looking straight and hard at the

girl. “She had blue eyes. They sparkled like sea water under the sun.”

The straightness of his glance took her breath. She herself was tall, her

skin was brown, and she knew she had dark-blue eyes. Her mirror told her

that there was life in them!

“Well,” said the Kid, “after a couple of days, I got sick. Very sick. My

mother began to worry. There was hell in the air!”

He looked up, as one suddenly struck to the heart by an irresistible

pain.

“Yes,” said the girl, barely whispering. “Yes?”

“The cows kept plugging along. I was sick, but my brain was all right. I

mean, I knew everything that was happening around me. I watched those

cows get thinner and thinner The flesh melted off them like the tallow

off candles. They turned into skeletons. It was a terrible thing to sit

there on the wagon seat and watch them dying on their feet. It was a

terrible thing to sit and watch it.”

“Go on!” breathed the girl. “What happened?”

“One of them died. I remember her. She was big Spot, we used to call her.

She was hard milking, and she was mean with her horns. But we got to love

her on that march through the desert. She pulled two thirds of the load.

Then she didn’t get up one morning. She was dead.

“There we were, stuck in the sands. There wasn’t very far to go, now, to

get to the grasslands, and one night I heard my father begging my mother

to go ahead and get to safety. He would wangle me through—me and the

wagon.

“Well, after Spot died, there was no chance of that. Mother wouldn’t

leave. They made a pack of everything that they dared to carry along.

They left the old wagon. They loaded me onto the back of the other cow.

She was old Red. One horn had been broken off. The other one curled in

and touched her between the eyes. She had eyes like a deer and a shape

like a coal barge. You know the way cows are.”

“Yes,” said the girl.

“They loaded me and part of the pack on top of old Red. Well, she was

pretty far gone. Her backbone stuck up like a ridge of rocks. I was

pretty weak. They had to hold me on her. They didn’t dare to tie me,

because every minute they thought that she might drop. And I could feel

her weaving under me. Staggering, and then going on. She was used to

pain, I suppose. It never occurred to her to lie down and give up.

“We went on for two days. At night, I used to stand in front of her and

rub her face, and she would curl out her long, dry tongue, and it felt

like a rasp on my hand.

“The third day, she went down with a bump and a slump. She was stone

dead.

“But she had done her part.

“Over to the north, we could see a green mist, and we knew that that was

the grass country. The edge of it.

“My father took me in his arms. I was too weak to walk. We went across

the rest of the desert and got to the grasslands, all right. My father

and I did, I mean.”

“Your mother—” said the girl, in horror.

“Oh, she came through, also,” said the Kid. “But a good deal of her was

left behind on that trail. She lasted through to the winter. I could see

her dying from day to day. So could my father. After a while she stayed

in her bed, and then died. The trail took too much out of her. She never

could get rested again.”

The girl placed her hands over her eyes.

At last she said: “And the men who did it? The cowards—the devils who

stole your stock?”

“Well,” said the Kid, “that’s a funny thing. You know that a mule lasts a

long time. Nine years later, when I was fifteen, I saw the mule that had

been stolen, and naturally I was a little curious. I started following

its back trail, and I looked up the five men, one by one.”

“They were all alive?” she asked.

“Only one is alive now,” said the Kid, and, lifting his head, he looked

at her in such a way that the blood turned to ice water in her veins.

To think of this matter calmly and from a distance, there was nothing

strange in the fact that the Kid had just implied that he had killed four

men, one after another. He had a reputation that attributed stranger and

more terrible deeds than this to him. But to be there in the quiet of the

woods alone with him was another matter. The friendliness in his blue

eyes upset her. And then he seemed amazingly young. There was not a trace

of a wrinkle about his eyes, and the only line in his face was a single

incision at the side of his mouth which appeared, now and then, when the

rest of his features were gravely composed, and gave him a look of

smiling cynically to himself. Whatever cruelties and desperate actions he

was guilty of, it seemed also manifest that he was as generous as cruel,

as manly as fierce.

Then, suddenly, she asked him: “Did you kill all of those men?”

“I?” said the Kid.

He smiled at her.

“You don’t think that I ought to ask you that,” she agreed, “and I don’t

suppose that I should. You’ve never told a soul, I suppose?”

“No, I’ve never told a soul, and I never intend to.”

She took her place on the log, she turned about on it to face him, and,

resting an elbow on her knee and her chin in the cool, slender palm of

her hand, she studied the Kid as he never had been studied before. He

looked straight back at her, but it was not easy.

“Well,” said she, “I don’t lose anything by asking, I suppose.”

“Are you asking me to tell you?”

“Yes, that’s what I’m asking.”

He still had in his hand the knife with which he had been whittling. That

whittling, she now saw, was no real use of the edge of the steel, but a

mere testing of it, while the whittler produced long, translucent

shavings which fel! as light as strips of paper to the ground, and slowly

dried, and warped, and curled. Now he flicked the knife into the air. It

whirled over and over in a solid wheel of silver that disappeared with a

thud. The blade had driven down into the earth its full length, and the

hilt had thumped heavily home.

“That’s a weighted knife,” said the girl.

“Yes. It’s weighted.”

He pulled it out and looked down the steel, which was hardly tarnished by

the moisture of the ground. He began to wipe and polish the blade slowly

and carefully.

“I asked about the four killings,” said the girl. “You won’t talk about

it, Kid?”

At this, he laughed a little.

“Do you expect that I’ll answer?”

“I sort of do expect you to,” said she.

“Well, tell me why.”

“Because I want to get to know you, and I hope that you’ll want to get to

know me.”

The Kid started a little. He looked at her in amazement, and in

bewilderment, and suddenly he seemed to her younger than ever before.

There was actually a slight tinge of red in his cheeks, and at the sight

of this color, she could have laughed, outright. But she swallowed her

triumph with a fierce satisfaction.

In fact, he was taken quite off balance.

“That’s fair enough,” said the Kid. “Friends as much as you like. Do you

have to know my story, first?”

“I’d like to, of course.”

“Would you have to?” asked the Kid.

He smiled in the way he had, secretly, to himself, as though he were

criticizing both himself and her, and wondering at the way he allowed

himself to be drawn out.

“Yes,” said the girl, calmly and firmly.

“Well,” said he, “the newspapers have written me up a good deal, and what

they leave out, you’ll find almost anybody willing to fill in—on a good

long winter evening when the fire’s burning well and the pipes are

drawing.”

She nodded.

“I know that sort of talk,” said she. “But I’m after facts.”

“You’d make an exchange, I suppose?” said the Kid.

“Of course I will. I have some dark spots of my own to show.”

He balanced the knife on the tip of a forefinger. It stood up as straight

and steady as a candle flame upon a windless night. “Well,” she said.

“I’m waiting to make the bargain. You ought to have me for a friend.”

“Yes?” said he, in query, but very

Comments (0)