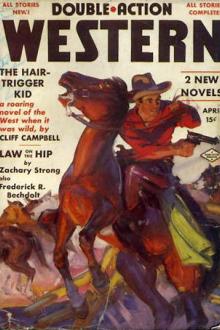

The Hair-Trigger Kid by Max Brand (best sci fi novels of all time TXT) 📕

"The curtain ain't up," said the sheriff, "but I reckon that the stage is set and that they's gunna be an entrance pretty pronto."

"Here's somebody coming," said Georgia, gesturing toward the farther end of the street.

"Yeah," said the sheriff, "but he's comin' too slow to mean anything."

"Slow and earnest wins the race," said another.

They were growing impatient; like a crowd at a bullfight, when the entrance of the matador is delayed too long.

"We're wasting the day," said Milman to his family. "That's a long ride ahead of us."

"Don't go now," said Georgia. "I've got a tingle in my finger tips that says something is going to happen."

Other voices were rising, jesting, laughing, when some one called out something at the farther end of the veranda, and instantly there was a wave of silence that spread upon them all.

"What is it?" whispered Milman to the sheriff.

"Shut up!" said the sheriff. "They say th

Read free book «The Hair-Trigger Kid by Max Brand (best sci fi novels of all time TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Max Brand

- Performer: -

Read book online «The Hair-Trigger Kid by Max Brand (best sci fi novels of all time TXT) 📕». Author - Max Brand

After this fourth narrative had ended, Georgia got up from the log and

hastily crossed the clearing. She walked back and forth for a moment.

breathing deeply. And the Kid, watching her through half-closed eyes,

continued to smoke, letting the cigarette fume between his fingers, most

of the time, but now and then lifting it in leisurely fashion to his

lips.

“You don’t really care what I think?” she demanded stopping suddenly in

front of him.

He seemed to rouse himself from a dream, starting violently. “Care?” he

echoed. “Of course I care.”

“Ah, not a rap!” said she.

“More,” answered the Kid, “than I care about the opinion of any other

person in the world.”

He said it so seriously that she stepped back a little. She put up her

head, but her face was pale, and the color would not come back into it.

“I’m not Carmelita,” said she.

“No,” answered the Kid, with perfect calm. “I wouldn’t dream of trying to

flirt with you.”

She watched him closely.

“I’m trying to get words together,” she said.

“Take your time,” said the Kid. “I know you’re going to hit hard, but I’m

ready to take the punch.”

At last she said. “I’ve never heard, and I’ve never dreamed of anything

like the four stories you’ve told me. I don’t want to believe them. I

won’t believe them. You’ve made up four horrible things—the most

horrible that you could conceive, and you’ve strung them together for the

sake of giving me a shock!”

“My dear,” said the Kid, “there’s nothing but the gospel truth in what

I’ve told you. Not a word but the exact truth.”

Staring at him fixedly, she knew that he meant what he said. “Then—” she

cried out.

She stopped the words; and the Kid, with his faint smile, watched her and

waited.

“You be the judge and the jury, now,” said he. “You can find me guilty

and hang me, too.”

“Why have you told me all this?” she asked him, almost passionately.

“Because you asked me to,” said the Kid.

“No,” she replied firmly. “That’s not it, I think. Merely asking wouldn’t

make you do it, I know!”

“I wanted you to know about me,” said the Kid. “That’s why I told you.”

“You wanted me to know?” she cried. “That’s it.”

“Will you tell me one thing more?”

“I probably will.”

“Did you take a pleasure out of what you did to each of those four men?”

He answered instantly: “When I started with each one, I would have

enjoyed feeding him into a fire, inch by inch. I would have enjoyed

hearing him howl like a fiend. But before the end, I admit that I was

sick of it, each time.”

“Then why did you keep on?”

“Because each time the business was done so thoroughly that at the end it

didn’t matter what I put my hand to. The thing always got outside of my

control. Turk Reming’s reputation that he loved and was proud of was gone

completely before he was killed. Harry Dill’s business was ruined, and

his happiness with it. Oliver’s self-confidence which he’d always been

able to trust like bed rock, was knocked to pieces under his feet. And

finally, Mickie Munroe had turned into an old man. Toward the end I

pitied each one of them. But I pitied them too late.”

“Suppose,” said the girl, “that you’re judged, one day, just as you’ve

judged them?”

He nodded frankly.

“I understand perfectly what you mean,” said the Kid. He looked up to

where a woodpecker was chiseling busily at the trunk of a tree, the

rapping of his incredible beak making a purr like that of a riveter. Down

fell a little thin shower of chips as the tree surgeon drilled for the

grub.

“Some day I’ll be judged,” said the Kid. “It’ll be a black day for me.

Mind you, I haven’t tried to excuse what I’ve done. And yet, if I had to

do it over again, I’d do it. I’d go through the same steps in the same

way.”

“What would drive you?” asked the girl. “There’s no real remorse in you

for what you’ve done, then? What would drive you on? Pity for your

mother’s death?”

“No,” said the Kid, after a moment of consideration. “Not that. She’s in

my mind, now and then, of course. So’s my father, and the pain in his

face. But what haunted me always was the memory of those two old milk

cows swaying and heaving under the yoke, and finally dying for us. Well,

not for us. It was the death of my mother; and my father would have been

better dead, I suppose. But those poor beasts did their work for me. I

used to think of them, I tell you, and the heat of that desert, and the

way old Red wobbled and staggered under me—I used to think of that when

I was working on those four in the final stages.”

“And there’ll be a fifth man?” said the girl. “As sure as I’m alive to

deal with him.”

“It’s Billy Shay!” she broke out suddenly.

“No,” said he.

“You’re not going to tell me, of course.”

“I am, though. It’s because I have to tell you that, that I told you all

the rest that went before.”

“Who is it, then?”

“His name is John Milman,” said the Kid.

He rose as she rose. Then, with a quick step forward, he caught her under

the arms, steadied her, and lowered her back to the log.

“I’m not going to faint!” she said through her teeth.

Her head fell. There was no trace of color in her face. “I won’t cave

in,” she repeated fiercely, faintly.

In a rush, then, the blood came back to her, and her head seemed to

clear.

“That’s a ghastly way to joke!” she said to him.

He took his hands gingerly from her, as though still not sure that she

was strong enough to sit upright, unsupported.

“If it were a joke, it would be ghastly,” he admitted. “It’s bad enough

even when it’s taken seriously.”

“Are you trying to tell me,” said the girl, “that my own father—my John

Milman—my mother’s husband—that he—was one of the five men that

night?”

As she spoke, the wind changed, grew a little in force, and brought to

them a vaguely melancholy sound from the horizon.

“Your father, your mother’s husband, your John Milman, he was one of the

five,” said the Kid.

“You’ve heard it, but it’s not true!” said the girl. “Why, it would have

been after I was born—after we were settled down here—after—why, you

think that you can make me believe that?”

“I think I can,” said he. “I’ve made myself believe it.”

“A hard job, that!” she said fiercely. “You wanted to believe. You’ve

simply wanted to find subjects to torture, and you hardly cared who’ But

this time—” She altered her voice and exclaimed: “Will you tell me what

makes you think it could possibly be he?”

“I’ll tell you,” said the Kid. “It was night, as I said. And I was sick,

so that you’d think that I couldn’t have seen very well. But the fact is

that they were quite free and easy. The law was a pretty dull affair,

those years ago. Blind, mostly, and no memory at all. So they didn’t

bother to wear masks, and they didn’t trouble about turning away when

they lighted cigarettes. I remember those faces, the way pictures slip

into the brain of a sick child and stay there for reference. I remember

Turk Reming laughing and showing his white teeth, while he held a match

to light the cigarette of another man—a middle-sized fellow, with a good

forehead, and good features altogether. That one had a cleft chin, and

halfway down the right side of his jaw there was a small, reddish spot,

like the mark of a bullet, or a birthmark, perhaps—”

He stopped and the girl, moistening her white lips, watched him. She was

breathing hard. The laboring of her heart choked her.

“What are you going to do?” she asked.

“I don’t know,” said the Kid. “That’s why I was glad to talk things over

with you.”

“You actually mean murder!” said the girl.

“Not with a gun,” said the Kid. “They didn’t use guns on my father and

mother, or on old Spot and Red. No, not with a gun.”

“There’s no other way that you can harm him!” said Georgia.

“Well, perhaps not,” said the Kid seriously.

“You can air his past as much as you please, but you’ll never ruin his

reputation. He’s spent too many years doing fine things. He’s filled the

whole range with his charities! I don’t care what your methods of

detestable blackmail are, you’ll never be able to destroy him the way you

did the cheap ruffians and fools!”

“There’s a great deal in what you say, of course,” said the Kid. “He

seems to have gone pretty straight since that night. Oh, I’ve looked him

over before, and I’ve always put if off, and put it off.”

She grew, if possible, paler still. Faint, bluish shadows began to appear

beneath her eyes.

“You mean that you’ve been watching him?”

“Oh, for years!” said the Kid. “He had the mule, you see. It was his

house that I found the first of all.”

She pressed her hands suddenly across her face, and jerked them down

again.

The Kid, watching her, went on: “A gray mule. Gray when we had it, and

nearly silver when I saw it again when I was fifteen. There was a

barbed-wire cut across his chest, a thing you don’t often see in mules.

They’re altogether too wise, usually, to—”

“Blister!” cried the girl. “It’s old Blister that you mean!”

He nodded.

“If you found my father, the first of all the five, why did you go away

without harming him? Because you knew in spite of anything, that he is a

good man!”

“I went away because of you,” said the Kid.

“Because of me?”

“You used to ride old Blister.”

“Why, I learned to ride on him. He didn’t know how to make a mistake.

He—”

She stopped, wretchedly tormented. Her lips twitched and her eyes were

haunted.

“One day you were riding him up the trail through the hills behind your

place. Up through those hills, yonder. You passed a youngster, dressed

mostly in rags. He was wearing one shoe and one moccasin. He was sitting

by a spring taking a rest, and you told him that if he went down to the

ranch house, he’d get something worth while.”

“I remember his blue eyes,” said the girl, “and—”

She stopped short again, her lips parting.

“It was you!” said she.

“Yeah,” drawled the Kid. “It was I, all right. That evening I went down

and looked things over. You were in the room where the piano is. Your

mother was playing; you were singing; your father was asleep in his

chair, but you kept on singing to the open window. You were only a

youngster, but you were singing love songs to the dark of that window.

And I was out there in the dark, watching.”

He made a pause, as if to remember the scene more clearly.

“Since then,” said the Kid, “I’ve come back three times,

Comments (0)