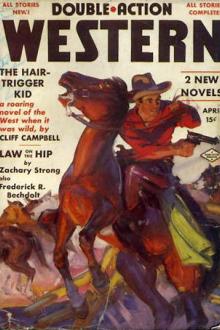

The Hair-Trigger Kid by Max Brand (best sci fi novels of all time TXT) 📕

"The curtain ain't up," said the sheriff, "but I reckon that the stage is set and that they's gunna be an entrance pretty pronto."

"Here's somebody coming," said Georgia, gesturing toward the farther end of the street.

"Yeah," said the sheriff, "but he's comin' too slow to mean anything."

"Slow and earnest wins the race," said another.

They were growing impatient; like a crowd at a bullfight, when the entrance of the matador is delayed too long.

"We're wasting the day," said Milman to his family. "That's a long ride ahead of us."

"Don't go now," said Georgia. "I've got a tingle in my finger tips that says something is going to happen."

Other voices were rising, jesting, laughing, when some one called out something at the farther end of the veranda, and instantly there was a wave of silence that spread upon them all.

"What is it?" whispered Milman to the sheriff.

"Shut up!" said the sheriff. "They say th

Read free book «The Hair-Trigger Kid by Max Brand (best sci fi novels of all time TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Max Brand

- Performer: -

Read book online «The Hair-Trigger Kid by Max Brand (best sci fi novels of all time TXT) 📕». Author - Max Brand

to get another view of the camp fire and to strain his eyes toward the

figures which were near it. For, from that distance, they could see forms

indistinctly, moving about in the yellow red of the firelight.

Those who waited in that excited group had something else to think of, a

moment later, for a rider came up to them at wild speed, and young

Georgia Milman’s voice called out frantically to know if her father was

there.

“Aye,” said Milman, after a moment of hisitation. “I’m here, Georgia.

What brought you out?”

He rode out to meet her, and she, wheeling her horse, went with him a

sufficient distance to cover the sound of their voices from the ears of

the others.

“What is it, Georgia?” he asked her.

She was half weeping with relief at finding him.

“I’ve come like mad all the way from the house,” she said. “I saw Tex

Marshall on the other side of Hurry Creek and he said that you’d come

around here. Father, I’ve come out to tell you that Mother and I don’t

care what’s happened in the past. We don’t care. You’re ours.”

He reached for her through the starlight and found her hand in his with a

strong grip, worthy of a man.

“Your mother, too, Georgia?” he asked her.

“Yes, Mother, too. Of course!”

“She’s always known that there was something wrong,” said Milman. “But—I

can only thank God and the two of you. Georgia, some day I’ll be able to

tell you a story that will be hard to believe. So hard that I couldn’t

try to tell it today, when you taxed me.”

“I believe it already,” she told him loyally. “Oh, Dad, it’s the three of

us against the world. D’you think Mother or I could fail you now, when

the bottom is falling out of everything?”

Something like a groan welled up in the throat of Milman. He crushed

Georgia’s hand and then let it fall.

“I’m going to talk it all out to the two of you,” said he. “But not now.

There’s something else to think about now. You saw the explosion?”

“Where?”

“In the hollow there in Dixon’s camp.”

“Explosion?”

“Doesn’t that camp fire look big to you?”

“Yes it does. What happened?”

“That’s what we don’t know. We only know that the Kid left Bud Trainor

and lowered himself by Trainor’s lariat into the gorge of the upper

creek. He was trying to get to the camp of Dixon, inside the fence lines

where they’ve been keeping watch. We don’t know, but we suspect that the

Kid may have caused the explosion that we saw in the camp—and the

woodpile caught fire from it. Then there was a stampede of the horses

from the same direction. They broke out through the herds. We don’t know

what to make of it—”

“And the Kid didn’t come out with the horses?” asked the girl.

“No.”

“Then he’s back there in the camp!”

“We’ve no proof at all that he ever reached the camp. It seems humanly

impossible that he could have got down the wall of the ravine and—”

She cried out, choking away the sound miserably at the end. And that cry

stabbed her father with a quick and frantic pain.

“You care a frightful lot about him, Georgia?” said he.

“Aye,” said she. “A frightful lot!”

“He’s tried this crazy thing for your sake, Georgia?”

“For me? For me?” said the girl, agony in her voice. “No, no! Don’t you

see that what he means to do is to smash you as he smashed the other

four? How could he try to do anything for my sake, then? It’s not for me.

It’s the misery of the poor dumb cows that’s making him try to do what no

man can win through to!”

“I don’t know what to make of him,” declared the father. “There never was

another man like him. Who else in the world would try such a thing—for

the sake of dumb beasts?”

“There are no other men like him,” she said. “But what will become of him

and all of us, I don’t know. I don’t dare to guess. But he’s down there

in that camp, I’ll swear.”

“What makes you so sure?”

“Because he couldn’t fail. There’s no failure in him. He could die. I

know that. But it will take men to kill him. It’ll certainly take men to

kill him!”

They went back to the rest of the watchers and all stared anxiously down

toward the fire. It no longer threw up flames so brilliantly. The

strength of the burning had rotted away the woodpile and allowed it to

spill out on the side. A strong glow, constantly reddening, was thrown up

from this mass, but the light was much less clear and far-reaching.

“Who has a strong pair of glasses?” asked Milman.

“I have a pair,” said a puncher, “but they really ain’t any good for

night work.”

Then a rider came up to them, sweeping from the hollow at a gallop, in

spite of the slope.

And, as he came in, the shrill, piping voice of Davey Trainor cried out:

“He’s in there! He’s in there! I seen him!”

They swarmed suddenly around the boy. Here was excitement. The passion

that was in him seemed to illumine his face far more than the starlight.

“What did you see, Davey? Where’ve you been?”

“I wanted to go look. I couldn’t stay out here with the rest of you just

millin’ around and doin’ nothing’. I went and had a look. You can get

through the cows. The worst ones is out on this side. The ones inside is

pretty nigh dead with the thirst. I got through, anyway. I got through,

and I seen him!”

“Who, who? Davey, who d’you mean?”

“Who do I mean? I mean him that started the fire, and that busted the

fence, and that burned up their chuck and that burned up their wagons and

their wood supply, so’s they’re as bare as my hand of everything that

folks would need. The Kid—the Kid, of course! There ain’t anybody else

that could do such things, is there?”

“He’s there!” cried Bud Trainor. “I might’ve knowed that it was

him. I did know it. I felt the ache of it in my bones!” Tears began

to stream down the face of Georgia.

She pressed her hands against her eyes, but the tears pressed through and

her hands were wet.

It was the end, she felt. Yet she controlled the throes of her sobbing.

Dimly, she heard the voices of the men.

“Who’s gonna do something?” demanded the voice of Davey Trainor, sharp

and biting as the noise of a cricket on a hearth. “Who’s gonna get

started and do something for the Kid? He wouldn’t leave a partner down

there with them crooks! He wouldn’t just sit around and look and talk.

He’d be down there sure raisin’ hell for the sake of his bunky! Who’s

gonna start something up here, for him? I’ll make one!”

This fierce and piping voice silenced them, for a moment.

“There are twenty men down there,” said one of the punchers, sullenly.

“I’d take a chance for the Kid. But not no chance like that. It ain’t a

lot of wooly lambs that are down there with Dixon.”

Milman took charge of the cross-questioning of the lad. “Tell me, Davey,

just what you saw?”

“I’ll tell you,” said Davey. “When I got through the cows, I come to a

place where I seen that there was three or four gents workin’ to patch up

a gap that had been broke through the wire fencing. They was cussing a

good deal.

“I worked along, keepin’ on the edge of the darkness, which wasn’t none

too hard, because the light of that fire’s so bright that all of them

that are near it are sort of blinded, I reckon. Fifty feet from the fire,

it’s like they was lookin’ at black windows. They couldn’t see out no

farther. Anyway, I worked down the line.

“That camp is sure a wreck. The cook tent is just a black mess, that’s

all. Everything is gone, includin’ their hosses. All that they got on

their hands, it’s a pile of saddles and such.”

“But the Kid, the Kid!” exclaimed Milman impatiently.

“Yeah, and I’m coming to that. I got up the line, closer to the fire, and

there I seen a lot of the men standin’ around, and whisperin’, and

shakin’ their heads at each other. You’d think that they was standin’

around and lookin’ at the devil or a ten-foot rattler. But it was the

Kid. He was stretched out, there. They had his hands and his feet tied. I

gathered from what I heard them say that he’d ‘ve got clean away on the

back of one of the hosses, if it wasn’t that the one he was ridin’

bareback had had a tumble and broke its own neck, and dropped the Kid. He

was senseless, but while I was there, he woke up, and sat up. Jiminy,

before that, I pretty nigh thought that he was dead!”

“What else?” asked Milman. “What else did you see?”

“D’you think I’d wait there?” demanded the youngster. “D’you think that

I’d wait there till they murdered him?”

“Murdered him?” cried out Georgia Milman suddenly, and her voice rang

sharp and thin in the air, almost like the excited yipping of Davey

himself.

“Sure they’ll murder him,” said Davey, “unless we do something about it.

Surely they’ll murder him. D’you think that that bunch of yeggs would

ever let the Kid loose to go wanderin’ around and pickin’ ‘em off? Why,

it would be pretty jolly for the Kid, wouldn’t it, to have that many

gents to trace down and bump off? It would keep him happy pretty night

all the rest of his life, wouldn’t it?”

“I suppose that it would,” said one of the punchers. “What can we do?”

“Ride down, ride down!” said Davey desperately. “Ride down and make a

try. They’s five of you here. You’re something. You can make a try for

him. You can sure make a try to help him. You wouldn’t be letting the Kid

get bumped off, Buck, would you? You wouldn’t let the Kid go like that,

Charlie? I know you wouldn’t. Mr. Milman, you say something to ‘em!”

“There’s nothing for me to say,” said Milman, after a moment of quiet. “I

know that I’m going down to do what I can!”

“There are twenty of them, father!” cried Georgia. “What could you do?

It’s a lost cause. You’re only throwing yourself away!”

But her heart leaped in her throat, and she knew the answer almost before

she heard it.

“It may be a lost cause,” said Milman, “but it’s my cause. And if the Kid

is brave enough to die for us, we’ll have to die for him. Georgia, so

long for a little while!”

He rode off.

“I’m number two in this party!” said Bud Trainor, and instantly his horse

was beside that of the rancher.

But the other three cow-punchers did not move to join the two. Two

against twenty! Aye, or even five against twenty, considering who the

twenty were, seemed sickening odds. Besides, these were not gunmen or

professional fighters. They had been hired to ride range, not to shoot it

Comments (0)