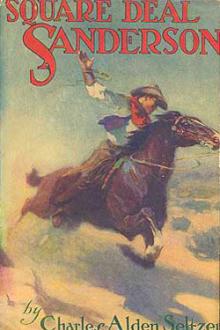

Square Deal Sanderson by Charles Alden Seltzer (fiction book recommendations TXT) 📕

They descended the slope of the hill, still talking. Evidently,Sanderson's silence had completely convinced them that they had killedhim.

But halfway down the hill, one of the men, watching the rock nearSanderson as he walked, saw the muzzle of Sanderson's rifle projectingfrom between the two rocks.

For the second time since the appearance of Sanderson on the scene theman discharged his rifle from the hip, and for the second time hemissed the target.

Sanderson, however, did not miss. His rifle went off, and the man fellwithout a sound. The other, paralyzed from the shock, stood for aninstant, irresolute, then, seeming to discover from where Sanderson'sbullet had come, he raised his rifle.

Sanderson's weapon crashed again. The second man shuddered, spunviolently around, and pitched headlong down the slope.

Sanderson came from behind the rock, grinning mirthlessly. He knewwhere his bullets had gone, and he took no precaut

Read free book «Square Deal Sanderson by Charles Alden Seltzer (fiction book recommendations TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Charles Alden Seltzer

- Performer: -

Read book online «Square Deal Sanderson by Charles Alden Seltzer (fiction book recommendations TXT) 📕». Author - Charles Alden Seltzer

Dale wheeled and faced Miss Bransford. His face reddened angrily, but he managed to smile.

"It's too late, Miss Bransford. The evidence is all in. There's got to be rules to govern such cases as this. Because you own the steers is no sign you've got a right to defeat the aims of justice. I'd like mighty well to accommodate you, but I've got my duty to consider, an' I can't let him off. Ben Nyland has got to hang, an' that's all there is to it!"

There came a passionate outcry from Peggy Nyland; and then she had her arms around her brother's neck, sobbing that she would never let him be hanged.

Miss Bransford's eyes were blazing with rage and scorn as they challenged Dale's. She walked close to him and said something in a low tone to him, at which he answered, though less gruffly than before, that it was "no use."

Miss Bransford looked around appealingly; first at the pale, anemic little man with big eyes, who shifted his feet and looked uncomfortable; then her gaze went to Sanderson who, resting his left elbow on the pommel of the saddle, was watching her with squinting, quizzical eyes.

There was an appeal in Miss Bransford's glance that made the blood leap to Sanderson's face. Her eyes were shining with an eloquent yearning that would have caused him to kill Dale—if he had thought killing the man would have been the means of saving Ben Nyland.

And then Mary Bransford was at his side, her hands grasping his, holding them tightly as her gaze sought his and held it.

"Won't you please do something?" she pleaded. "Oh, if it only could be! That's a mystery to you, perhaps, but when I spoke to you before I was going to ask you if—if— But then, of course you couldn't be—or you would have spoken before."

Sanderson's eyes glowed with a cold fire. He worked his hands free, patted hers reassuringly, and gently pushed her away from Streak.

He swung down from the saddle and walked to Dale. The big man had his back turned to Sanderson, and when Sanderson reached him he leaned over his shoulder and said gently:

"Look here, Dale."

The latter wheeled, recognizing Sanderson's voice and snarling into the latter's face.

"Well?" he demanded.

Sanderson grinned mildly. "I reckon you've got to let Ben Nyland off, Dale—he ain't guilty. Mebbe I ought to have stuck in my gab before, but I was figurin' that mebbe you wouldn't go to crowdin' him so close. Ben didn't steal no steers; he run them into his corral by my orders."

Dale guffawed loudly and stepped back to sneer at Sanderson. But he had noted the steadiness of the latter's eyes and the sneer faded.

"Bah!" he said. "Your orders! An' who in hell are you?"

"I'm Bill Bransford," said Sanderson quietly, and he grinned mirthlessly at Dale over the two or three feet of space that separated them.

For several seconds Dale did not speak. A crimson stain appeared above the collar of his shirt and spread until it covered his face and neck, leaving his cheeks poisonously bloated and his eyes glaring.

But the steady eyes and the cold, deliberate demeanor of Sanderson did much to help Dale regain his self-control—which he did, while Mary Bransford, running forward, tried to throw her arms around Sanderson's neck. She was prevented from accomplishing this design by Sanderson who, while facing Dale, shoved the girl away from him, almost roughly.

"There's time for that after we've settled with Dale," he told the girl gruffly.

Dale had recovered; he sneered. "It's easy enough to make a claim like that, but it's another thing to prove it. How in hell do we know you're Bill Bransford?"

Sanderson's smile was maddening. "I ain't aimin' to prove nothin'—to you!" he said. But he reached into a pocket, drew out the two letters he had taken from the real Bransford's pocket, and passed them back to Mary Bransford, still facing Dale.

He grinned at Dale's face as the latter watched Mary while she read the letters, gathering from the scowl that swept over the other's lips that Mary had accepted them as proof of his identity.

"You'll find the most of that thousand you sent me in my slicker," he told the girl. And while Mary ran to Streak, unstrapped the slicker, tore it open, and secured the money, Sanderson watched Dale's face, grinning mockingly.

"O Will—Will!" cried the girl joyously behind Sanderson.

Sanderson's smile grew. "Seems to prove a heap, don't it?" he said to Dale. "I know a little about law myself. I won't be pressin' no charge against Nyland. Take your rope off him an' turn him free. An' then mebbe you'll be accommodatin' enough to hit the breeze while the hittin's good—for me an' Miss—my sister's sort of figurin' on a reunion—bein' disunited for so long."

He looked at Dale with cold, unwavering eyes until the latter, sneering, turned and ordered his men to remove the rope from Nyland. With his hands resting idly on his hips he watched Dale and the men ride away. Then he shook hands mechanically with Nyland, permitted Peggy to kiss him—which she did fervently, and led her brother away. Then Sanderson turned, to see Mary smiling and blushing, not more than two or three feet distant.

He stood still, and she stepped slowly toward him, the blush on her face deepening.

"Oh," she said as she came dose to him and placed her hands on his shoulders, "this seems positively brazen—for you seem like a stranger to me."

Then she deliberately took both his cheeks in her hands, stood on the tips of her toes and kissed him three or four times, squarely on the lips.

"Why, ma'am—" began Sanderson.

"Mary!" she corrected, shaking him.

"Well, ma'am—Mary, that is—you see I ain't just——"

"You're the dearest and best brother that ever lived," she declared, placing a hand over his mouth, "even though you did stay away for so many years. Not another word now!" she warned as she took him by an arm and led him toward the ranchhouse; "not a word about anything until you've eaten and rested. Why, you look tired to death—almost!"

Sanderson wanted to talk; he wanted to tell Mary Bransford that he was not her brother; that he had assumed the rôle merely for the purpose of defeating Dale's aim. His sole purpose had been to help Mary Bransford out of a difficult situation; he had acted on impulse—an impulse resulting from the pleading look she had given him, together with the knowledge that she had wanted to save Nyland.

Now that the incident was closed, and Nyland saved, he wanted to make his confession, be forgiven, and received into Mary's good graces.

He followed the girl into the house, but as he halted for an instant on the threshold, just before entering, he looked hack, to see the little, anemic man standing near the house, looking at him with an odd smile. Sanderson flushed and made a grimace at the little man, whereat the latter's smile grew broad and eloquent.

"What's eatin' him, I wonder?" was Sanderson's mental comment. "He looked mighty fussed up while Dale was doin' the talkin'. Likely he's just tickled—like the rest of them."

Mary led Sanderson into the sitting-room to a big easy-chair, shoved him into it, and stood behind him, running her fingers through his hair. Meanwhile she talked rapidly, telling him of the elder Bransford's last moments, of incidents that had occurred during his absence from the ranch; of other incidents that had to do with her life at a school on the coast; of many things of which he was in complete ignorance.

Desperate over his inability to interrupt her flow of talk, conscious of the falseness of his position, squirming under her caresses, and cursing himself heartily for yielding to the absurd impulse that had placed him in so ridiculous a predicament, Sanderson opened his month a dozen times to make his confession, but each time closed it again, unsuccessful.

At last, nerved to the ordeal by the knowledge that each succeeding moment was making his position more difficult, and his ultimate pardon less certain, he wrenched himself free and stood up, his face crimson.

"Look here, ma'am——"

"Mary!" she corrected, shaking a finger at him.

"Mary," he repeated tonelessly, "now look here," he went on hoarsely. "I want to tell you that I ain't the man you take me to be. I'm——"

"Yes, you are," she insisted, smiling and placing her hands on his shoulders. "You are a real man. I'll wager Dale thinks so; and Peggy Nyland, and Ben. Now, wait!" she added as he tried to speak. "I want to tell you something. Do you know what would have happened if you had not got here today?

"I'll tell you," she went on again, giving him no opportunity to inject a word. "Dale would have taken the Double A away from me! He told me so! He was over here yesterday, gloating over me. Do you know what he claims? That I am not a Bransford; that I am merely an adopted daughter—not even a legally adopted one; that father just took me, when I was a year old, without going through any legal formalities.

"Dale claims to have proof of that. He won't tell me where he got it. He has some sort of trumped-up evidence, I suppose, or he would not have talked so confidently. And he is all-powerful in the basin. He is friendly with all the big politicians in the territory, and is ruthless and merciless. I feel that he would have succeeded, if you had not come.

"I know what he wants; he wants the Double A on account of the water. He is prepared to go any length to get it—to commit murder, if necessary. He could take it away from me, for I wouldn't know how to fight him. But he can't take it away from you, Will. And he can't say you have no claim to the Double A, for father willed it to you, and the will has been recorded in the Probate Court in Las Vegas!

"O Will; I am so glad you came," she went on, stroking and patting his arms. "When I spoke to you the first time, out there by the stable, I was certain of you, though I dreaded to have you speak for fear you would say otherwise. And if it hadn't been you, I believe I should have died."

"An' if you'd find out, now, that I ain't Will Bransford," said Sanderson slowly, "what then?"

"That can't be," she said, looking him straight in the eyes, and holding his gaze for a long time, while she searched his face for signs of that playful deceit that she expected to see reflected there.

She saw it, evidently, or what was certainly an excellent counterfeit of it—though Sanderson was in no jocular mood, for at that moment he felt himself being drawn further and further into the meshes of the trap he had laid for himself—and she smiled trustfully at him, drawing a deep sigh of satisfaction and laying her head against his shoulder.

"That can't be," she repeated. "No man could deceive a woman like that!"

Sanderson groaned, mentally. He couldn't confess now and at the same time entertain any hope that she would forgive him.

Nor could he—knowing what he knew now of Dale's plans—brutally tell her the truth and leave her to fight Dale single-handed,

And there was still another consideration to deter him from making a confession. By impersonating her brother he had raised her hopes high. How could he tell her that her brother had been killed, that he had buried him in a desolate section of a far-off desert after taking his papers and his money?

He felt, from her manner when he had tentatively asked her to consider the possibility of his not being her brother, that the truth would kill her, as she had said.

Worse, were he now to inform her of what had happened in the desert, she might not believe

Comments (0)