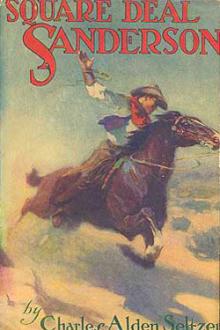

Square Deal Sanderson by Charles Alden Seltzer (fiction book recommendations TXT) 📕

They descended the slope of the hill, still talking. Evidently,Sanderson's silence had completely convinced them that they had killedhim.

But halfway down the hill, one of the men, watching the rock nearSanderson as he walked, saw the muzzle of Sanderson's rifle projectingfrom between the two rocks.

For the second time since the appearance of Sanderson on the scene theman discharged his rifle from the hip, and for the second time hemissed the target.

Sanderson, however, did not miss. His rifle went off, and the man fellwithout a sound. The other, paralyzed from the shock, stood for aninstant, irresolute, then, seeming to discover from where Sanderson'sbullet had come, he raised his rifle.

Sanderson's weapon crashed again. The second man shuddered, spunviolently around, and pitched headlong down the slope.

Sanderson came from behind the rock, grinning mirthlessly. He knewwhere his bullets had gone, and he took no precaut

Read free book «Square Deal Sanderson by Charles Alden Seltzer (fiction book recommendations TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Charles Alden Seltzer

- Performer: -

Read book online «Square Deal Sanderson by Charles Alden Seltzer (fiction book recommendations TXT) 📕». Author - Charles Alden Seltzer

Again Sanderson groaned in spirit. To confess to her would be to destroy her; to withhold the confession and to continue to impersonate her brother was to act the rôle of a cad.

Sanderson hesitated between a choice of the two evils, and was lost. For she gave him no time for serious and continued thought. Taking him by an arm she led him into a room off the sitting-room, shoving him through the door laughingly.

"That is to be your room," she said. "I fixed it up for you more than a month ago. You go in there and get some sleep. Sleep until dusk. By that time I'll have supper ready. And then, after supper, there are so many things that I want to say to you. So get a good sleep!"

She closed the door and went out, and Sanderson sank into a chair. Later, he locked the door, pulled the chair over near a window—from which he got a good view of the frowning butte at the edge of the level—and stared out, filled with a sensation of complete disgust.

"Hell," he said, after a time, "I'm sure a triple-plated boxhead, an' no mistake!"

Sanderson did not sleep. He sat at the window all afternoon, dismally trying to devise way of escape from the dilemma. He did not succeed. He had gone too far now to make a confession sound reasonably convincing; and he could not desert the girl to Dale. That was not to be thought of. And he was certain that if he admitted the deception, the girl would banish him as though he were a pestilence.

He was hopelessly entangled. And yet, continuing to ponder the situation, he saw that he need not completely yield to pessimism. For though circumstances—and his own lack of foresight—had placed him in a contemptible position—he need not act the blackguard. On the contrary, he could admirably assume the rôle of protector.

The position would not be without its difficulties, and the deception meant that he could never be to Mary Bransford what he wanted to be to her; but he could at least save the Double A for her. That done, and his confession made, he could go on his way, satisfied that he had at least beaten Dale.

His decision made, Sanderson got up, opened the door a trifle, and looked into the sitting-room. It was almost dusk, and, judging from the sounds that reached his ears from the direction of the kitchen, Mary intended to keep her promise regarding "supper."

Feeling guilty, though grimly determined to continue the deception to the end—whatever the end might be—Sanderson stole through the sitting-room, out through the door leading to the porch, and made his way to a shed lean-to back of the kitchen.

There he found a tin washbasin, some water, and a towel, and for ten minutes he worked with them. Then he discovered a comb, and a broken bit of mirror fixed to the wall of the lean-to, before which he combed his hair and studied his reflection. He noted the unusual flush on his cheeks, but grinned brazenly into the glass.

"I'm sure some flustered," he told his reflection.

Arrayed for a second inspection by Mary Bransford, Sanderson stood for a long time at the door of the lean-to, trying to screw up his courage to the point of confronting the girl.

He succeeded finally, and walked slowly to the outside kitchen door, where he stood, looking in at Mary.

The girl was working over the stove, from which, floating to the doorway where Sanderson stood, came various delicious odors.

Mary was arrayed in a neat-fitting house dress of some soft print material, with a huge apron over it. Her sleeves were rolled slightly above the elbows; her face was flushed, and when she turned and saw Sanderson her eyes grew very bright.

"Oh," she said; "you are up! I was just thinking of calling you!" She ran to him, threw her arms around him, and, in spite of his efforts to evade her, she kissed him first on one cheek and then on the other.

Noting his reluctance she stepped back and looked reprovingly at him.

"You seem so distant, Will. And I am so glad to see you!"

"I ain't used to bein' kissed, I expect."

"But—by your sister!"

He reddened. "I ain't seen you for a long time, you know. Give me time, an' mebbe I'll get used to it."

"I hope so," she smiled. "I should feel lost if I could not kiss my brother. You have washed, too!" she added, noting his glowing face and his freshly combed hair.

"Yes, ma'am."

"Mary!" she corrected.

"Mary," grinned Sanderson.

Mary turned to the stove. "You go out and find a chair on the porch," she directed, over her shoulder. "I'll have supper ready in a jiffy. It's too hot for you in here."

Sanderson obeyed. From the deeply crimson hue of his face it was apparent that the heat of the kitchen had affected him. That, at least, must have been the reason Mary had ordered him away. His face felt hot.

He found a chair on the porch, and he sank into it, feeling like a criminal. There was a certain humor in the situation. Sanderson felt it, but could not appreciate it, and he sat, hunched forward, staring glumly into the dusk that had settled over the basin.

He had been sitting on the porch for some minutes when he became aware of a figure near him, and he turned slowly to see the little, anemic man standing not far away.

"Cooling off?" suggested the little man.

Sanderson straightened. "How in hell do you know I'm hot?" he demanded gruffly.

The little man grinned. "There's signs. Your face looks like you'd had it in an oven. Now, don't lose your temper; I didn't mean to offend you."

The little man's voice was placative; his manner gravely ingratiating. Yet Sanderson divined that the other was inwardly laughing at him. Why? Sanderson did not know. He was aware that he must seem awkward in the rôle of brother, and he suspected that the little man had noticed it; possibly the little man was one of those keen-witted and humorously inclined persons who find amusement in the incongruous.

There was certainly humor in the man's face, in the glint of his eyes, and in the curve of his lips. His face was seamed and wrinkled; his ears were big and prominent, the tips bending outward under the brim of a felt hat that was too large for him; his mouth was large, and Sanderson's impression of it was that it could not be closed far enough to conceal all the teeth, but that the lips were continually trying to stretch far enough to accomplish the feat.

Sanderson was certain it was that continual effort of the muscles of the lips that gave to his mouth its humorous expression.

The man was not over five feet and two or three inches tall, and crowning his slender body was a head that was entirely out of proportion to the rest of him. He was not repulsive-looking, however, and a glance at his eyes convinced Sanderson that anything Providence had taken from his body had been added, by way of compensation, to his intellect.

Sanderson found it hard to resent the man's seeming impertinence. He grinned reluctantly at him.

"Did I tell you you'd hurt my feelin's?" he inquired. "What oven do you think I had my head in?"

"I didn't say," grinned the little man. "There's places that are hotter than an oven. And if a man has never been a wolf with women, it might be expected that he'd feel sort of warm to be kissed and fussed over by a sister he's not seen for a good many years. He'd seem like a stranger to her—almost."

Sanderson's eyes glowed with a new interest in the little man.

"How did you know I wasn't a wolf with women?"

"Shucks," said the other; "you're bashful, and you don't run to vanity. Any fool could see that."

"I ain't been introduced to you—regular," said Sanderson, "but you seem to be a heap long on common sense, an' I'd be glad to know you. What did you say your name was?"

"Barney Owen."

"What you doin' at the Double A? You ought be herd-ridin' scholars in a district schoolhouse."

"Missed my calling," grinned the other. "I got to know too much to teach school, but didn't know enough to let John Barleycorn alone. I'm a drifter, sort of. Been roaming around the north country. Struck the basin about three weeks ago. Miss Bransford was needing men—her father—yours, too, of course—having passed out rather sudden. I was wanting work mighty had, and Miss Bransford took me on because I was big enough to do the work of half a dozen men."

His face grew grave. Sanderson understood. Miss Bransford had hired Owen out of pity. Sanderson did not answer.

The little man's face worked strangely, and his eyes glowed.

"If you hadn't come when you did, I would have earned my keep, and Alva Dale would be where he wouldn't bother Miss Bransford any more," he said.

Sanderson straightened. "You'd have shot him, you mean?"

Owen did not speak, merely nodding his head.

Sanderson smiled. "Then I'm sort of sorry come when I did. But do you think shootin' Dale would have ended it?"

"No; Dale has friends." Owen leaned toward Sanderson, his face working with passion. "I hate Dale," he said hoarsely. "I hate him worse than I hate any snake that I ever saw. I hadn't been here two days when he sneered at me and called me a freak. I'll kill him—some day. Your coming has merely delayed the time. But before he dies I want to see him beaten at this game he's tryin' to work on Miss Bransford. And I'll kill any man that tries to give Miss Bransford the worst of it.

"You've got a fight on your hands. I know Dale and his gang, and they'll make things mighty interesting for you and Miss Bransford. But I'll help you, if you say the word. I'm not much for looks—as you can see—but I can sling a gun with any man I've ever met.

"I'd have tried to fight Dale alone—for Miss Bransford's sake—but I realize that things are against me. I haven't the size, and I haven't the nerve to take the initiative. Besides, I drink. I get riotously drunk. I can't help it. I can't depend on myself. But I can help you, and I will."

The man's earnestness was genuine, and though Sanderson had little confidence in the other's ability to take a large part in what was to come, he respected the spirit that had prompted the offer. So he reached out and took the man's hand.

"Any man that feels as strongly as you do can do a heap—at anything," he said. "We'll call it a deal. But you're under my orders."

"Yes," returned Owen, gripping the hand held out to him.

"Will!" came Mary's voice from the kitchen, "supper is ready!"

Owen laughed lowly, dropped Sanderson's hand, and slipped away into the growing darkness.

Sanderson got up and faced the kitchen door, hesitating, reluctant again to face the girl and to continue the deception. Necessity drove him to the door, however, and when he reached it, he saw Mary standing near the center of the kitchen, waiting for him.

"I don't believe you are hungry at all!" she declared, looking keenly at him. "And do you know, I think you blush more easily than any man I ever saw. But don't let that bother you," she added, laughing; "blushes become you. Will," she went on, tenderly pressing his arm as she led him through a door into the dining-room, "you are awfully good-looking!"

"You'll have me gettin' a swelled head if you go to talkin' like that," he said, without looking at her.

"Oh, no; you couldn't be vain if you tried. None of the Bransfords were ever vain—or conceited. But they all have had good

Comments (0)