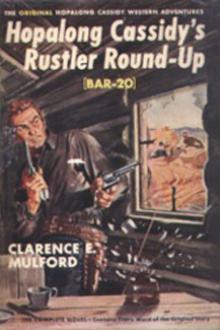

''Bring Me His Ears'' by Clarence E. Mulford (howl and other poems TXT) 📕

"I know how you feel, Mr. Boyd. Have you seen your father since you landed?"

Tom reluctantly shook his head. "It would only reopen the old bitterness and lead to further estrangement. No man shall ever speak to me again as he did--not even him. If you should see him, Jarvis, tell him I asked you to assure him of my affection."

"I shall be glad to do that," replied the clerk. "You missed him by only two days. He asked for you and wished you success, and said your home was open to you when you returned to resume your studies. I think, in his heart, he is proud of you, but too stubborn to admit it." As he spoke he chanced to glance through the window of the store. "Don't look around," he warned. "I want to tell you t

Read free book «''Bring Me His Ears'' by Clarence E. Mulford (howl and other poems TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Clarence E. Mulford

- Performer: -

Read book online «''Bring Me His Ears'' by Clarence E. Mulford (howl and other poems TXT) 📕». Author - Clarence E. Mulford

He and his companion stopped in the bow and looked at the merry camp on shore, both sensing an undertone of trouble. Give the vile, frontier liquor time to work in such men and anything might be the outcome.

He put his lips close to his companion's ear: "Mr. Cooper, did you notice anyone hurry into the cabin just before I came in? Anyone who seemed excited and in a hurry?"

Cooper considered a moment: "No," he replied. "I would have seen any such person. Something wrong?"

"Schoolcraft, now; and that Mexican friend of his," prompted Tom. "Did they leave the cabin before you saw me come in?"

"No; they both were where you saw them for an hour or two before you showed up. I'm dead certain of that because of the interest Schoolcraft seemed to be taking in me. I don't know why he should single me out for his attentions, for he don't look like a gambler. I never saw him before that little fracas you had with him on the levee. Something up?"

"No," slowly answered Tom. "I was just wondering about something."

"Nope; he was there all the time," the merchant assured him. "Seems to me I heard about some trouble you had in Santa Fe last year. Anything serious?"

"Nothing more than a personal quarrel. I happened to get there after they had started McLeod's Texans on the way to Mexico City, and learned that they had been captured." He clenched his fists and scowled into the night. "One of the pleasant things I learned from a man who saw it, was the execution of Baker and Howland. Both shot in the back. Baker was not killed, so a Mexican stepped up and shot him through the heart as he lay writhing on the ground. The dogs tore their bodies to pieces that night." He gripped the railing until the blood threatened to burst from his finger tips. "I learned the rest of it, and the worst, a long time later."

Cooper turned and stared at him. "Why, man, that was in October! Late in October! How could you have been there at that time, and here, in this part of the country, now? You couldn't cross the prairies that late in the year!"

"No; I wintered at Bent's Fort," replied Tom. "I hadn't been in Independence a week before I took the boat down to St Louis, where you first saw me. There were four of us in the party and we had quite a time making it. Well, reckon I'll be turning in. See you tomorrow."

He walked rapidly toward the cabin, glanced in and then went to his quarters. Neither Schoolcraft nor the Mexican were to be seen, for they were in the former's stateroom with a third man, holding a tense and whispered conversation. The horse-dealer apparently did not agree with his two companions, for he kept doggedly shaking his head and reiterating his contentions in drunken stubbornness that, no matter what had been overheard, Tom Boyd was not going to Oregon, but back to Santa Fe. He mentioned Patience Cooper several times and insisted that he was right. While his companions were not convinced that they were wrong they, nevertheless, agreed that there should be no more knife throwing until they knew for certain that the young hunter was not going over the southwest trail.

Schoolcraft leered into the faces of his friends. "You jest wait an' see!" He wagged a finger at them. "Th' young fool is head over heels in love with her; an' he'll find it out afore she jines th' Santa Fe waggin train. Whar she goes, he'll go. I'm drunk; but I ain't so drunk I don't know that!"

CHAPTER IV.TOM CHANGES HIS PLANS

Dawn broke dull and cold, but without much wind, and when Tom awakened he heard the churning of the great paddle wheel, the almost ceaseless jangling of the engine room bell and the complaining squeaks of the hard-worked steering gear. A faint whistle sounded from up river, was answered by the Missouri Belle, and soon the latter lost headway while the two pilots exchanged their information concerning the river. Again the paddles thumped and thrashed and the boat shook as it gathered momentum.

On deck he found a few early risers, wrapped in coats and blankets against the chill of the morning hour. The overcast sky was cold and forbidding; the boiling, scurrying surface of the river, sullen and threatening. Going up to the hurricane deck he poked his head in the pilot house.

"Come on in," said the pilot "We won't go fur today. See that?"

Tom nodded. The small clouds of sand were easily seen by eyes such as his and as he nodded a sudden gust tore the surface of the river into a speeding army of wavelets.

"Peterson jest hollered over an' said Clay Point's an island now, an' that th' cut-off is bilin' like a rapids. Told me to look out for th' whirlpool. They're bad, sometimes."

"To a boat like this?" asked Tom in surprise.

"Yep. We give 'em all a wide berth." The wheel rolled over quickly and the V-shaped, tormented ripple ahead swung away from the bow. "That's purty nigh to th' surface," commented the pilot. "Jest happened to swing up an' show its break in time. Hope we kin git past Clay before th' wind drives us to th' bank. Look there!"

A great, low-lying cloud of sand suddenly rose high into the air like some stricken thing, its base riven and torn into long streamers that whipped and writhed. The gliding water leaped into short, angry waves, which bore down on the boat with remarkable speed. As the blast struck the Missouri Belle she quivered, heeled a bit, slowed momentarily, and then bore into it doggedly, but her side drift was plain to the pilot's experienced eyes.

"We got plenty o' room out here fer sidin'," he observed; "but 'twon't be long afore th' water'll look th' same all over. We're in fer a bad day." As he spoke gust after gust struck the water, and he headed the boat into the heavier waves. "Got to keep to th' deepest water now," he explained. "Th' snags' telltales are plumb wiped out. I shore wish we war past Clay. There ain't a decent bank ter lie ag'in this side o' it."

For the next hour he used his utmost knowledge of the river, which had been developed almost into an instinct; and then he rounded one of the endless bends and straightened out the course with Clay Point half a mile ahead.

"Great Jehovah!" he muttered. "Look at Clay!"

The jutting point, stripped bare of trees, was cut as clean as though some great knife had sliced it. Under its new front the river had cut in until, as they looked, the whole face of the bluff slid down into the stream, a slice twenty feet thick damming the current and turning it into a raging fury. Some hundreds of yards behind the doomed point the muddy torrent boiled and seethed through its new channel, vomiting trees, stumps, brush and miscellaneous rubbish in an endless stream. Off the point, and also where the two great currents came together again behind it two great whirlpools revolved with sloping surfaces smooth as ice, around which swept driftwood with a speed not unlike the horses of some great merry-go-round. The vortex of the one off the point was easily ten feet below the rim of its circumference, and the width of the entire affair was greater than the length of the boat. A peeled log, not quite water-soaked, reached the center and arose as vertical as a plumb line, swayed in short, quick circles and then dove from sight. A moment later it leaped from the water well away from the pool and fell back with a smack which the noise of the wind did not drown. To starboard was a rhythmic splashing of bare limbs, where a great cottonwood, partly submerged, bared its fangs. To the right of that was a towhead, a newly formed island of mud and sand partly awash.

The pilot cursed softly and jerked on the bell handle, the boat instantly falling into half speed. He did not dare to cut across the whirlpool, the snag barred him dead ahead, and it was doubtful if there was room to pass between it and the towhead; but he had no choice in the matter and he rang again, the boat falling into bare steerageway. If he ran aground he would do so gently and no harm would be done. So swift was the current that the moment he put the wheel over a few spokes and shifted the angle between the keel-line and the current direction, the river sent the craft sideways so quickly that before he had stopped turning the wheel in the first direction he had to spin it part way back again. The snag now lay to port, the towhead to starboard, and holding a straight course the Missouri Belle crept slowly between them. There came a slight tremor, a gentle lifting to port, and he met it by a quick turn of the wheel. For a moment the boat hung pivoted, its bow caught by a thrusting side current and slowly swinging to port and the snag. A hard yank on the bell handle was followed by a sudden forward surge, a perceptible side-slip, a gentle rocking, and the bow swung back as the boat, entirely free again, surged past both dangers.

The pilot heaved a sigh of relief. "Peterson didn't say nothin' about th' snag or th' towhead," he growled. Then he grinned. "I bet he rounded inter th' edge o' th' whirler afore he knowed it was thar! Now that I recollect it he did seem a mite excited."

"Somethin' like a boy explorin' a cave, an' comin' face to face with a b'ar," laughed Tom. "I recken you fellers don't find pilotin' monotonous."

"Thar ain't no two trips alike; might say no two miles, up or down, trip after trip. Here comes th' rain, an' by buckets; an' thar's th' place I been a-lookin' fer. Th' bank's so high th' wind won't hardly tech us."

He signaled for half speed and then for quarter and the boat no sooner had fallen into the latter than her bow lifted and she came to a grating stop. The crew, which had kept to shelter, sprang forward without a word and as the captain crossed the bow deck the great spars were being hauled forward. After the reversed paddles had shown the Belle to be aground beyond their help, the spars were put to work and it was not long before they pushed her off again, and a few minutes later she nosed against the bank.

The pilot sighed and packed his pipe. "Thar!" he said, explosively. "Hyar we air, an' we ain't a-goin' on ag'in till we kin see th' channel. No, sir, not if we has ter stay hyar a week!"

Tom led the way below and paused at the foot of the companionway as he caught sight of Patience. He glowed

Comments (0)