All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (best new books to read .TXT) 📕

CHAPTER II

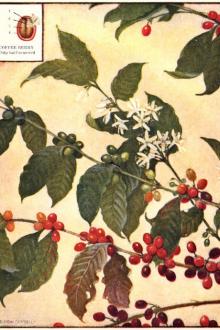

HISTORY OF COFFEE PROPAGATION

A brief account of the cultivation of the coffee plant in the Old World, and of its introduction into the New--A romantic coffee adventure Page 5

CHAPTER III

EARLY HISTORY OF COFFEE DRINKING

Coffee in the Near East in the early centuries--Stories of its origin--Discovery by physicians and adoption by the Church--Its spread through Arabia, Persia, and Turkey--Persecutions and Intolerances--Early coffee manners and customs Page 11

CHAPTER IV

INTRODUCTION OF COFFEE INTO WESTERN EUROPE

When the three great temperance beverages, cocoa, tea, and coffee, came to Europe--Coffee first mentioned by Rauwolf in 1582--Early days of coffee in Italy--How Pope Clement VIII baptized it and made it a truly Christian beverage--The first Europe

Read free book «All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (best new books to read .TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: William H. Ukers

- Performer: -

Read book online «All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (best new books to read .TXT) 📕». Author - William H. Ukers

Jabez Burns, Inventor, Manufacturer, Writer

Jabez Burns was a person of real importance to the American coffee trade from 1864, when he began to manufacture his improved roaster, until his death, at the age of sixty-two, in 1888. His success depended more on unusual character than unusual ability, although he was really gifted as regards mechanical invention. He loved to acquire practical information, and arrived confidently at common-sense conclusions; and he exercised a wide and helpful influence, because he liked to give expression to opinions that he considered sound and useful.

Mr. Burns was born in London in 1826. The family moved soon after to Dundee, Scotland, and came to New York in 1844. They were people of small means and independent thinking. The father, William G. Burns, had been more interested in the Chartist social movement than in any settled business activity. An uncle, also named Jabez Burns, became a popular Baptist preacher in London.

The first winter in America found youthful Jabez teaching a country school at Summit, N.J. Then he began in New York (1844–45) as teamster for Henry Blair, a prosperous coffee merchant who attended a little "Disciples" church in lower Sixth Avenue where many Scottish families congregated. There also Burns met Agnes Brown, daughter of a Paisley weaver, and married her in 1847. A brave young pair they were, who found all sorts of odd riches—just as if a fast-growing family could somehow make up for a slow-growing income. There were hopes, too, that the contrivances Burns kept inventing might bring wealth; and some extra money did come from the sale of early patents, including one in 1858 for the Burns Addometer, a primitive adding machine.

But Mr. Burns had continued regularly in the employ of coffee and spice firms, and at one time he was bookkeeper for Thomas Reid's Globe Mills. He advanced slowly, because he lacked real trading talent; but he was learning all about the handling of goods, from purchase to final delivery; and when he quit bookkeeping for the old Globe Mills, and began to build his patent roaster, he could advise clients reliably about every factory detail.

He was soon looked on as an authority. He wrote some articles for the American Grocer, a series on "Food Adulteration" being reprinted; and in 1878, he began the quarterly publication of his thirty-two-page Spice Mill, which soon became a monthly, and gained the interested attention of practically the entire coffee and spice trade.

Through the columns of this paper, in circulars, by letters, and in a pocket volume called the Spice Mill Companion, he distributed information on coffee, spices, and baking powder, and gave valuable advice to beginners in the coffee-roasting business. Not a few coffee roasters were started on the way to fortune by the counsel of Jabez Burns. He died in New York, September 16, 1888.

Jabez Burns founded the business of Jabez Burns & Sons in 1864, beginning the manufacture of his patent coffee roaster at 107 Warren Street, New York. Since then, there have been four removals. In December, 1908, the business moved to its present uptown location, at the northwest corner of Eleventh Avenue and Forty-third Street, occupying a six-story building which was doubled in size in 1917. This Burns factory has been referred to as "the unique coffee-machinery workshop", the greatest establishment of its kind in the United States.

Upon the death of its founder the business was continued; first, as the firm of Jabez Burns & Sons, composed of his sons, Jabez, Robert, and A. Lincoln Burns; and later, in 1906, incorporated as Jabez Burns & Sons, Inc., with Robert Burns as president, Jabez Burns as vice-president, and A. Lincoln Burns as secretary and treasurer. Jabez Burns died August 6, 1908. The present officers are: Robert Burns, president; A. Lincoln Burns, vice-president; William G. Burns, general manager; and C.H. Maclachlan, secretary and treasurer.

A. Lincoln Burns succeeded his father as editor of the Spice Mill. William H. Ukers was made editor in 1902, and he continued until 1904, when he left to assume editorial direction of The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal.

Coffee-Trade Booms and Panics

In the last fifty years there have been many spectacular attempts to corner the coffee market in Europe and the United States. The first notable occurrence of this kind did not originate in the trade itself. It took place in 1873, and was known as the "Jay Cooke panic", being brought about by the famous panic of that name in the stock market.

As a result of the Jay Cooke failure, it was impossible to obtain money from the banks. Hence buyers were forced to keep out of the coffee market; and as a consequence, the price for Rios dropped from twenty-four cents to fifteen cents in the course of the trading period of one day[349].

Another interesting development during that year was of foreign origin. A coffee syndicate was organized in Europe, financed by the powerful German Trading Company of Frankfort, with agencies in London, Rotterdam, Antwerp, and Brazil. For more than eight years this proved to be a highly successful undertaking, largely controlling the principal producing and consuming markets.

As far as the American coffee trade is concerned, the first sensational upheaval took place in 1880–81. This period witnessed the collapse of the first great coffee trade combination in this country—the so-called "syndicate", comprising O.G. Kimball, B.G. Arnold, and Bowie Dash, sometimes known as the "trinity".

The period of high coffee prices, commencing in 1870, had greatly stimulated production in many Mild-coffee producing countries, as well as in Brazil, and as a consequence the syndicate found its burden becoming extremely heavy early in 1880. In January of that year our visible supply amounted roughly to 767,000 bags. While this was reduced to about 740,000 bags in July, the latter likewise proved to be decidedly burdensome, especially as another liberal crop was beginning to move in producing countries. The excessive volume of supplies was especially marked, because distributing trade during the summer was strikingly dull, as the majority of buyers were holding off, in view of the prospective liberal new crops. At that time Java coffee was a big item in American markets, whereas Santos was just about beginning to be a factor.

The syndicate found that it had its hands full supporting the Brazil grades, and hence had to let the Javas go. As a result, the latter, which had sold at twenty-four and three-quarters cents in January, 1880, fell to nineteen and one-half cents in July, to eighteen cents in November and to sixteen cents in December. As a matter of fact, the syndicate was practically the only buyer of Brazil coffee during the fall of 1880; and as a consequence, Rios, which had started the year at fourteen and one-half to sixteen and one-quarter cents, were down to twelve and three-quarters cents in December, 1880, and had dropped nine and one-half cents when the break in the market culminated in June, 1881.

The first whispers of financial troubles growing out of these adverse conditions were heard in October, 1880; and on the 27th of that month the first failure was announced—that of C. Risley & Co., with liabilities placed at $800,000 and assets at $400,000. This firm had been doing business in the local market for about thirty years. The efforts of the receivers to dispose of this company's large stock naturally served to accelerate the decline; and the final impetus came on December 6, when the New York trade heard of the death, two days previously, of O.G. Kimball, of Boston, one of the most prominent merchants there. This precipitated the big crash of December 7, when B.G. Arnold & Co., the largest New York firm, suspended with estimated liabilities of $750,000 to $1,000,000. The official statement later placed the liabilities at $2,157,914, and assets at $1,400,000, of which $884,198 were secured. Within three days this failure was followed by the suspension of Bowie Dash & Co., with liabilities estimated at $1,400,000.

For weeks thereafter there was virtually no market. With all of these distress holdings pressing for liquidation, buyers, as was natural, were extremely timid. In the meantime, the import arrivals showed further enlargement at various southern ports, as well as at New York. Total arrivals at this port during 1881 were almost 12,400,000 pounds heavier than for the preceding year. The growing importance of Santos as a market factor was demonstrated by the fact that shipments from there in 1881 were 1,198,625 bags, compared with about 628,900 bags in 1876–77. According to the best informed members of the trade at that time, the losses sustained by the various firms that were forced to the wall aggregated between $5,000,000 and $7,000,000.

The utterly demoralized conditions prevailing while this collapse was in progress, and the practical elimination of a market in the true sense of the word, furnished the principal impetus for the organization of the New York Coffee Exchange. At that time, the Havre market was the only one with an exchange. The local body was organized in December, 1881, and started business in March, 1882.

The Cable Break of 1884

The second noteworthy movement, embracing an advance of four to four and one-half cents and a recession of slightly more than three cents, covered a period of about eight months shortly after the Exchange was organized. Various local and out-of-town firms were interested in the bulge which carried Rio coffee in this market from about seven cents in July, 1883, up to eleven and one-half cents late in November. By the middle of December, the price had fallen to nine and one-quarter cents, the final break to eight and one-quarter cents occurring late in March of the following year. At that time, there was no direct cable communication with Brazil; and as a result of a temporary break in the roundabout service by way of Portugal, the New York and Baltimore agents of the Brazilian syndicate were unable to put up additional margins in this market, and their accounts were closed out. This happened on a Saturday; and by the following Monday, partial cable remittances arrived and all accounts were settled in full with interest from Saturday to Monday.

The Great Boom

What is generally described as "the great boom" of the coffee trade occurred in 1886–87, and had its inception in unsatisfactory crop news from Brazil. The crop of 1887–1888, it was estimated, would be extremely small; and it turned out to be only 3,033,000 bags. These advices and low estimates led to the formation of a "bull" clique, comprising operators in New York, Chicago, New Orleans, Brazil, and Europe, who set a price of twenty-five cents for December contracts as their goal. Toward the end of June, 1886, when this campaign started, No. 7 Rio in New York was worth about seven and one-half cents, with June contracts on the Exchange quoted at seven and sixty-five hundredths cents. With Brazilian crop news still more discouraging, the advance thereafter was almost continuous, and on June 1, 1887, December contracts sold at twenty-two and one-quarter cents—a new high price record, that was not exceeded for thirty-two years, when twenty-four and sixty-five hundredths cents were paid for July contracts in June, 1919. After reaching twenty-two and one-quarter cents, prices suffered an abrupt reversal. Ten days later the closing price for December was twenty-one and four-tenth cents. Then the real crash began. On Saturday, June 11, the panic started with another claim of cable trouble; and in the short session, December coffee

Comments (0)