All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (best new books to read .TXT) 📕

CHAPTER II

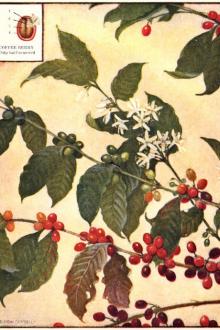

HISTORY OF COFFEE PROPAGATION

A brief account of the cultivation of the coffee plant in the Old World, and of its introduction into the New--A romantic coffee adventure Page 5

CHAPTER III

EARLY HISTORY OF COFFEE DRINKING

Coffee in the Near East in the early centuries--Stories of its origin--Discovery by physicians and adoption by the Church--Its spread through Arabia, Persia, and Turkey--Persecutions and Intolerances--Early coffee manners and customs Page 11

CHAPTER IV

INTRODUCTION OF COFFEE INTO WESTERN EUROPE

When the three great temperance beverages, cocoa, tea, and coffee, came to Europe--Coffee first mentioned by Rauwolf in 1582--Early days of coffee in Italy--How Pope Clement VIII baptized it and made it a truly Christian beverage--The first Europe

Read free book «All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (best new books to read .TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: William H. Ukers

- Performer: -

Read book online «All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (best new books to read .TXT) 📕». Author - William H. Ukers

The method of preparing coffee for individual service in the Waldorf-Astoria, New York, which has been adopted by many first-class hotels and restaurants that do not serve urn-made coffee exclusively, is the French drip plus careful attention to all the contributing factors for making coffee in perfection, and is thus described by the hotel's steward:

Its story is told on page 614

A French china drip coffee pot is used. It is kept in a warm heater; and when the coffee is ordered, this pot is scalded with hot water. A level tablespoonful of coffee, ground to about the consistency of granulated sugar, is put into the upper and percolator part of the coffee pot. Fresh boiling water is then poured through the coffee and allowed to percolate into the lower part of the pot. The secret of success, according to our experience, lies in having the coffee freshly ground, and the water as near the boiling point as possible, all during the process. For this reason, the coffee pot should be placed on a gas stove or range. The quantity of coffee can be varied to suit individual taste. We use about ten percent more ground coffee for after dinner cups than we do for breakfast. Our coffee is a mixture of Old Government Java and Bogota.

C. Scotty, chef at the Hotel Ambassador, New York, thus describes the method of making coffee in that hostelry:

In the first place, it is essential that the coffee be of the finest quality obtainable; secondly, better results are obtained by using the French filterer, or coffee bag.

Twelve ounces of coffee to one gallon of water for breakfast.

Sixteen ounces of coffee to one gallon of water for dinner.

Boiling water should be poured over the coffee, sifoned, and put back several times. We do not allow the coffee grounds to remain in the urn for more than fifteen to twenty minutes at any time.

The coffee service at the best hotels is usually in silver pots and pitchers, and includes the freshly made coffee, hot milk or cream (sometimes both), and domino sugar.

Within the last year (1921) many of the leading hotels, and some of the big railway systems, have adopted the custom of serving free a demi-tasse of coffee as soon as the guest-traveler seats himself at the breakfast table or in the dining car. "Small blacks," the waiters call them, or "coffee cocktails," according to their fancy.

At the Pequot coffee house, 91 Water Street, New York, a noonday restaurant in the heart of the coffee trade, an attempt has been made to introduce something of the old-time coffee house atmosphere.

The Childs chain of restaurants recently began printing on its menus, in brackets before each item, the number of calories as computed by an expert in nutrition. Coffee with a mixture of milk and cream is credited with eighty-five calories, a well known coffee substitute with seventy calories, and tea with eighteen calories. The Childs chain of 92 restaurants serves 40,000,000 cups of coffee a year, made from 375 tons of ground coffee, and figuring an average of 53 cups to the pound.

The Thompson chain of one hundred restaurants serves 160,000 cups of coffee per day, or more than 58,000,000 cups per year.

Coffee Customs in South America

Argentine. Coffee is very popular as a beverage in Argentina. Café con léche—coffee with milk, in which the proportion of coffee may vary from one-fourth to two-thirds—is the usual Argentine breakfast beverage. A small cup of coffee is generally taken after meals, and it is also consumed to a considerable extent in cafés.

Brazil. In Brazil every one drinks coffee and at all hours. Cafés making a specialty of the beverage, and modeled after continental originals, are to be found a-plenty in Rio de Janeiro, Santos, and other large cities. The custom prevails of roasting the beans high, almost to carbonization, grinding them fine, and then boiling after the Turkish fashion, percolating in French drip pots, steeping in cold water for several hours, straining and heating the liquid for use as needed, or filtering by means of conical linen sacks suspended from wire rings.

The Brazilian loves to frequent the cafés and to sip his coffee at his ease. He is very continental in this respect. The wide-open doors, and the round-topped marble tables, with their small cups and saucers set around a sugar basin, make inviting pictures. The customer pulls toward him one of the cups and immediately a waiter comes and fills it with coffee, the charge for which is about three cents. It is a common thing for a Brazilian to consume one dozen to two dozen cups of black coffee a day. If one pays a social visit, calls upon the president of the Republic, or any lesser official, or on a business acquaintance, it is a signal for an attendant to serve coffee. Café au lait is popular in the morning; but except for this service, milk or cream is never used. In Brazil, as in the Orient, coffee is a symbol of hospitality.

In Chile, Paraguay and Uruguay, very much the same customs prevail of making and serving the beverage.

Coffee Drinking in Other Countries

In Australia and New Zealand, English methods for roasting, grinding, and making coffee are standard. The beverage usually contains thirty to forty percent chicory. In the bush, the water is boiled in a billy can. Then the powdered coffee is added; and when the liquid comes again to a boil, the coffee is done. In the cities, practically the same method is followed. The general rule in the antipodes seems to be to "let it come to a boil", and then to remove it from the fire.

In Cuba the custom is to grind the coffee fine, to put it in a flannel sack suspended over a receiving vessel, and to pour cold water on it. This is repeated many times, until the coffee mass is well saturated. The first drippings are repoured over the bag. The final result is a highly concentrated extract, which serves for making café au lait, or café noir, as desired.

In Martinique, coffee is made after the French fashion. In Panama, French and American methods obtain; as also in the Philippines.

The evolution of grinding and brewing methods—Coffee was first a food, then a wine, a medicine, a devotional refreshment, a confection, and finally a beverage—Brewing by boiling, infusion, percolation, and filtration—Coffee making in Europe in the nineteenth century—Early coffee making in the United States—Latest developments in better coffee making—Various aspects of scientific coffee brewing—Advice to coffee lovers on how to buy coffee, and how to make it in perfection

The coffee drink has had a curious evolution. It began, not as a drink, but as a food ration. Its first use as a drink was as a kind of wine. Civilization knew it first as a medicine. At one stage of its development, before it became generally accepted as a liquid refreshment, the berries found favor as a confection. As a beverage, its use probably dates back about six hundred years.

The protein and fat content, that is, the food value, of coffee, so far as civilized man is concerned, is an absolute waste. The only constituents that are of value are those that are water soluble, and can be extracted readily with hot water. When coffee is properly made, as by the drip method, either by percolation or filtration, the ground coffee comes in contact with the hot water for only a few minutes; so the major portion of the protein, which is not only practically insoluble, but coagulates on heating, remains in the unused part of the coffee, the grounds. The coffee bean contains a large percent of protein—fourteen percent. By comparing this figure with twenty-one percent of protein in peas, twenty-three percent in lentils, twenty-six percent in beans, twenty-four percent in peanuts, about eleven percent in wheat flour, and less than nine percent in white bread, we learn how much of this valuable food stuff is lost with the coffee grounds[373].

Though civilized man (excepting the inhabitants of the Isle de Groix off the coast of Brittany) does not use this protein content of coffee, in certain parts of Africa it has been put to use in a very ingenious and effective manner "from time immemorial" down to the present day. James Bruce, the Scottish explorer, in his travels to discover the source of the Nile in 1768–73, found that this curious use of the coffee bean had been known for centuries. He brought back accounts and specimens of its use as a food in the shape of balls made of grease mixed with roasted coffee finely ground between stones.

Other writers have told how the Galla, a wandering tribe of Africa—and like most wandering tribes, a warlike one—find it necessary to carry concentrated food on their long marches. Before starting on their marauding excursions, each warrior equips himself with a number of food balls. These prototypes of the modern food tablet are about the size of a billiard ball, and consist of pulverized coffee held in shape with fat. One ball constitutes a day's ration; and although civilized man might find it unpalatable, from the purely physiological standpoint it is not only a concentrated and efficient food, but it also has the additional advantage of containing a valuable stimulant in the caffein content which spurs the warrior on to maximum effort. And so the savage in the African jungle has apparently solved two problems; the utilization of coffee's protein, and the production of a concentrated food.

Further research shows that perhaps as early as 800 A.D. this practise started by crushing the whole ripe berries, beans and hulls, in mortars, mixing them with fats, and rounding them into food balls. Later, the dried berries were so used. The inhabitants of Groix, also, thrive on a diet that includes roasted coffee beans.

About 900, a kind of aromatic wine was made in Africa from the fermented juice of the hulls and pulp of the ripe berries[374].

Payen says that the first coffee drinkers did not think of roasting but, impressed by the aroma of the dried beans, they put them in cold water and drank the liquor saturated with their aromatic principles. Crushing the raw beans and hulls, and steeping them in water, was a later improvement.

It appears that boiled coffee (the name is anathema today) was invented about the year 1000 A.D. Even then, the beans were not roasted. We read of their use in medicine in the form of a decoction. The dried fruit, beans and hulls, were boiled in stone or clay cauldrons. The custom of using the sun-dried hulls, without roasting, still exists in Africa, Arabia, and parts of southern Asia. The natives of Sumatra neglect the fruit of the coffee tree and use the leaves to make a tea-like infusion. Jardin relates that in Guiana an agreeable tea is made by drying the young buds of the coffee tree, and rolling them on a copper plate slightly heated. In Uganda, the natives eat the raw berries; from bananas and coffee they make also a sweet, savory drink which is called menghai.

About 1200, the practise was common of making a decoction from the dried hulls alone. There followed

Comments (0)