All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (best new books to read .TXT) 📕

CHAPTER II

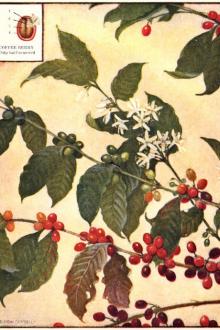

HISTORY OF COFFEE PROPAGATION

A brief account of the cultivation of the coffee plant in the Old World, and of its introduction into the New--A romantic coffee adventure Page 5

CHAPTER III

EARLY HISTORY OF COFFEE DRINKING

Coffee in the Near East in the early centuries--Stories of its origin--Discovery by physicians and adoption by the Church--Its spread through Arabia, Persia, and Turkey--Persecutions and Intolerances--Early coffee manners and customs Page 11

CHAPTER IV

INTRODUCTION OF COFFEE INTO WESTERN EUROPE

When the three great temperance beverages, cocoa, tea, and coffee, came to Europe--Coffee first mentioned by Rauwolf in 1582--Early days of coffee in Italy--How Pope Clement VIII baptized it and made it a truly Christian beverage--The first Europe

Read free book «All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (best new books to read .TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: William H. Ukers

- Performer: -

Read book online «All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (best new books to read .TXT) 📕». Author - William H. Ukers

The roasting of coffee is requisite for the production of both these qualities; but, to secure them in their full degree, it is necessary to conduct the process with some skill. The first thing to be done is to expose the raw coffee to the heat of a gentle fire, in an open vessel, stirring it continually until it assumes a yellowish colour. It should then be roughly broken,—a thing very easily done,—so that each berry is divided into about four or five pieces, when it must be put into the roasting apparatus. This, as most commonly used, is made of sheet-iron, and is of a cylindrical shape: it no doubt answers the purpose well, and is by no means a costly machine, but coffee may be very well roasted in a common iron or earthenware pot, the main circumstances to be observed being the degree to which the process is carried, and the prevention of partial burning, by constant stirring. One of the requisites for having good coffee is that it shall have been recently roasted.

Coffee should be ground very fine for use, and only at the moment when it is wanted, or the aromatic flavour will in some measure be lost. To extract all its good qualities, the powder requires two separate and somewhat opposite modes of treatment, but which do not offer any difficulty when explained. On the one hand, the fine flavour would be lost by boiling, while, on the other, it is necessary to subject the coffee to that degree of heat in order to extract its medicinal quality. The mode of proceeding, which, after many experiments, Mr. Donovan found to be the most simple and efficacious for attaining both these ends, was the following:—

The whole water to be used must be divided into two equal parts. One half must be put first to the coffee "cold", and this must be placed over the fire until it "just comes to a boil", when it must be immediately removed. Allowing it then to subside for a few moments the liquid must be poured off as clear as it will run. The remaining half of the water, which during this time should have been on the fire, must then be added "at a boiling heat" to the grounds, and placed on the fire, where it must be kept "boiling" for about three minutes. This will extract the medicinal virtue, and if then the liquid be allowed again to subside, and the clear fluid be added to the first portion, the preparation will be found to combine all the good properties of the berry in as great perfection as they can be obtained. If any fining ingredient is used it should be mixed with the powder at the beginning of the process.

Several kinds of apparatus, some of them very ingenious in their construction, have been proposed for preparing coffee, but they are all made upon the principle of extracting only the aromatic flavour, while Professor Donovan's suggestions not only enable us to accomplish that desirable object, but superadd the less obvious but equally essential matter of extracting and making our own all the medicinal virtues.

When Webster and Parkes published their Encyclopedia of Domestic Economy, London, 1844, they gave the following as "the most usual method of making coffee in England":

Put fresh ground coffee into a coffee-pot, with a sufficient quantity of water, and set this on the fire till it boils for a minute or two; then remove it from the fire, pour out a cupful, which is to be returned into the coffee-pot to throw down the grounds that may be floating; repeat this, and let the coffee-pot stand near the fire, but not on too hot a place, until the grounds have subsided to the bottom; in a few minutes the coffee will be clear without any other preparation, and may be poured into cups; in this manner, with good materials in sufficient quantity, and proper care, excellent coffee may be made. The most valuable part of the coffee is soon extracted, and it is certain that long boiling dissipates the fine aroma and flavour. Some make it a rule not to suffer the coffee to boil, but only to bring it just to the boiling point; but it is said by Mr. Donovan that it requires boiling for a little time to extract the whole of the bitter, in which he conceives much of the exhilarating qualities of the coffee reside.

This work had also the following to say on the clearing of coffee, which was then a much-mooted question:

The clearing of coffee is a circumstance demanding particular attention. After the heaviest parts of the grounds have settled, there are still fine particles suspended for some time, and if the coffee be poured off before these have subsided, the liquor is deficient in that transparency which is one test of its perfection; for coffee not well cleared has always an unpleasant bitter taste. In general, the coffee becomes clear by simply remaining quiet for a few minutes, as we have stated; but those who are anxious to have it as clear as possible employ some artificial means of assisting the clearing. The addition of a little isinglass, hartshorn shavings, skins of eels or soles, white of eggs, egg shells, etc., has been recommended for clearing; but it is evident that these substances, to produce their effect, which is upon the same principle as the fining of beer or wine, should be dissolved previously, for if put in without, it would require so much time to dissolve, that the flavour of the coffee would vanish.

Coffee-making devices of this period in England, in addition to the Rumford type of percolator and the popular coffee biggin, included Evans' machine provided with a tin air-float to which was attached a filter bag containing the coffee; Jones' apparatus, a pumping percolator; Parker's steam-fountain coffee maker, which forced the hot water upward through the ground coffee; Platow's patent filter, previously mentioned, a single vacuum glass percolator in combination with an urn; Brain's vacuum or pneumatic filter employing a "muslin, linen or shamoy leather filter" and an exhausting pump, designed for kitchen use; and Palmer's and Beart's pneumatic filtering machines of similar construction.

Cold infusions were common, the practise being to let them stand overnight, to be filtered in the morning, and only heated, not boiled.

Coffee grinding for these various types of coffee makers was performed by iron mills; the portable box mill being most favored for family use. "It consisted of a square box either of mahogany or iron japanned, containing in the interior a hollow cone of steel with sharp grooves on the inside; into this fits a conical piece of hardened iron or steel having spiral grooves cut upon its surface and capable of being turned round by a handle." There was a drawer to receive the finely ground coffee. Larger wall-mills employed the same grinding mechanism.

In 1855, Dr. John Doran wrote in his "Table Traits":

With regard to the making of coffee, there is no doubt that the Turkish method of pounding the coffee in a mortar is infinitely superior to grinding it in a mill, as with us. But after either method the process recommended by M. Soyer may be advantageously adopted; namely, "Put two ounces of ground coffee into a stew-pan, which set upon the fire, stirring the coffee round with a spoon until quite hot, then pour over a pint of boiling water; cover over closely for five minutes, pass it through a cloth, warm again, and serve."

From observations by G.W. Poore, M.D., London, 1883, we are given a glimpse of coffee making in England in the latter part of the nineteenth century. He said:

Those who wish to enjoy really good coffee must have it fresh roasted. On the Continent, in every well-regulated household, the daily supply of coffee is roasted every morning. In England this is rarely done.

If roasted coffee has to be kept, it must be kept in an air-tight vessel. In France, coffee used to be kept in a wrapper of waxed leather, which was always closely tied over the contained coffee. In this way the coffee was kept from contact with any air.

The Viennese say that coffee should be kept in a glass bottle closed with a bung, and that coffee should on no account be kept in a tin canister.

The coffee having been roasted, it has to be reduced to a coarse powder before the infusion is made. The grinding and powdering of coffee should be done just before it is wanted, for if the whole coffee seeds quickly lose their aroma, how much more quickly will the aroma be dissipated from coffee which has been reduced to a fine powder? Nothing need be said in the matter of coffee mills. They are common enough, varied enough, and cheap enough to suit all tastes.

To insure a really good cup of coffee attention must be given to the following points:

1. Be sure that the coffee is good in quality, freshly roasted, and fresh ground.

2. Use sufficient coffee. I have made some experiments on this point, and I have come to the conclusions that one ounce of coffee to a pint of water makes poor coffee, 11⁄2 ounces of coffee to a pint of water makes fairly good coffee, two ounces of coffee to a pint of water makes excellent coffee.

3. As to the form of coffee pot I have nothing to say. The varieties of coffee machines are very numerous and many of them are useless incumbrances. At the best, they can not be regarded as absolutely necessary. The Brazilians insist that coffee pots should on no account be made of metal, but that porcelain or earthenware is alone permissible. I have been in the habit of late of having my coffee made in a common jug provided with a strainer, and I believe there is nothing better.

4. Warm the jug, put the coffee into it, boil the water, and pour the boiling water on the coffee, and the thing is done.

5. Coffee must not be boiled, or at most it must be allowed just to "come to a boil", as cook says. If violent ebullition takes place, the aroma of the coffee is dissipated, and the beverage is spoiled.

The most economical way of making coffee is to put the coffee into a jug and pour cold water upon it. This should be done some hours before the coffee is wanted—over night, for instance, if the coffee be required for breakfast. The light particles of coffee will imbibe the water and fall to the bottom of the jug in course of time. When the coffee is to be used stand the jug in a saucepan of water or a bainmarie and place the outer vessel over the fire till the water contained in it boils. The coffee in this way is gently brought to the boiling point without violent ebullition, and we get the maximum extract without any loss of aroma.

Always make your coffee strong. Café au lait is much better if made with one-fourth strong coffee and three-fourths milk than if made half-and-half with a weaker coffee; this is evident.

It is a mistake to suppose that coffee can not be made without a great deal of costly and cumbersome apparatus.

The Continent. Rossignon has given us a general view of

Comments (0)