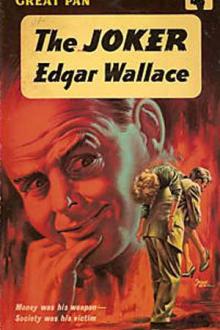

The Joker by Edgar Wallace (best inspirational books .txt) 📕

'I don't know,' said the older man vaguely. 'One could travel... '

'The English people have two ideas of happiness: one comes from travel, one from staying still! Rushing or rusting! I might marry but I don't wish to marry. I might have a great stable of race-horses, but I detest racing. I might yacht--I loathe the sea. Suppose I want a thrill? I do! The art of living is the art of victory. Make a note of that. Where is happiness in cards, horses, golf, women-anything you like? I'll tell you: in beating the best man to it! That's An Americanism. Where is the joy of mountain climbing, of exploration, of scientific discovery? To do better than somebody else--to go farther, to put your foot on the head of the next best.'

He blew a cloud of smoke through the open window and waited until the breeze had torn the misty gossamer into shreds and nothingness.

'When you're a millionaire you either

Read free book «The Joker by Edgar Wallace (best inspirational books .txt) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Edgar Wallace

- Performer: -

Read book online «The Joker by Edgar Wallace (best inspirational books .txt) 📕». Author - Edgar Wallace

The Joker

Edgar Wallace

1926

MR STRATFORD HARLOW was a gentleman with no particular call to hurry. By

every standard he was a member of the leisured classes, and to his

opportunities for lingering, he added the desire of one who was

pertinently curious.

The most commonplace phenomena interested Mr Harlow. He had all the

requisite qualities of an observer; his enjoyment was without the

handicap of sentimentality, a weakness which is fatal to accurate

judgement.

Leonardo da Vinci could stand by the scaffold using the dreadful floor as

his desk; and sketch the agonies of malefactors given to the torture. Mr

Harlow, no great lover of painters, thought well of Leonardo. He too

could stop to look at sights which sent the average man shuddering and

hurrying past; he could stop (even when he was really in a hurry) to

analyse the colour scheme in an autumn sunset, not to rhapsodise

poetically, but to mark down for his own information the quantities of

beauty.

He was a large man of forty-eight, fair and slightly bald. His

clean-shaven face was unlined, his skin without blemish. Pale blue eyes

are not accounted beautiful and the pallor of Mr Harlow’s eyes was such

that, seeing him for the first time, many sensitive people experienced a

shock, thinking he was sightless. His nose was big and long, and of the

same width from forehead to tip. He had very red, thick lips that seemed

to be pouting even when they were in repose. A rounded chin with a dimple

in the centre and unusually small cars, completes the description.

His powerful car was drawn up by the side of the road, its two near

wheels on the green verge, and Mr Harlow sat, one hand on the wheel,

watching the marshalling of the men in a field. In such moments of

contemplative reveries as these, splendid ideas were born in Stratford

Harlow’s mind, great schemes loomed out of the nowhere which is beyond

vision. And, curiously enough, prisons invariably had this inspirational

effect.

They were trudging now across the field, led by a lank warder, cheerful,

sunburnt men in prison uniform.

Tramp! Tramp! Tramp!

The convicts had reached the hard road and were coming towards him. The

leading warder glanced suspiciously at the well-dressed stranger, but the

gang were neither abashed nor distressed by this witness of their shame.

Rather, they carried themselves with a new perkiness as though conscious

of their value as an unusual spectacle. The first two files glanced

sideways and grinned in a friendly manner, half the third file followed

suit, but the second man looked neither left nor right. He had a scowl on

his face, a sneer on his thin lips and he lifted one shoulder in a shrug

of contemptuous defiance, delivered, as the watcher realised, not so much

towards the curious sightseer, but the world of free men which Mr Harlow

represented.

Twisting round in his seat, he watched the little column filing through

the Arch of Despair and out of sight through the gun-metal gates which he

could not see.

The motorist stepped on the starter and brought the car round in a

half-circle. Patiently he manoeuvred the long chassis until it headed

back towards Princetown. Tavistock and Ellenbury could wait a day—a week

if necessary. For here was a great thought to be shaped and exploited.

His car stopped noiselessly before the Duchy Hotel, and the porter came

running down the steps.

‘Anything wrong, sir?’

‘No. I thought I’d stay another day. Can I have the suite? If not, any

room will do.’

The suite was not let, he learnt, and he had his case carried upstairs.

It was then that he decided that Ellenbury, being within driving

distance, might come across the moor and save him the tedium of a day

spent in Tavistock. He picked up the telephone and in minutes Ellenbury’s

anxious voice answered him.

‘Come over to Princetown. I’m staying at the Duchy. Don’t let people see

that you know me. We will get acquainted in the smoke-room after lunch.’

Mr Harlow was eating his frugal lunch at a table overlooking the untidy

square in front of the Duchy, when he saw Ellenbury arrive: a small,

thin, nervous man, with white hair. Soon after the visitor came down to

the big dining-room, gazed quickly round, located Mr Harlow with a start,

and sat himself at the nearest table.

The dining-room was sparsely occupied. Two parties that had driven up

from Torquay ate talkatively in opposite corners of the room. An elderly

man and his stout wife sat at another table, and at a fourth, conveying a

curious sense of aloofness, a girl. Women interested Mr Harlow only in so

far as they were factors in a problem or the elements of an experiment;

but since he must classify all things he saw, he noticed, in his

cold-blooded fashion, that she was pretty and therefore unusual; for to

him the bulk of humanity bore a marked resemblance to the cheap little

suburban streets in which they lived, and the drab centres of commerce

where they found their livelihood.

He had once stood at the corner of a busy street in the Midlands and had

taken a twelve-hour census of beauty. In that period, though thousands

upon thousands hurried past, he had seen one passably pretty girl and two

that were not ill-favoured. It was unusual that this girl, who sat

sidefaced to him, should be pretty; but she was unusually pretty.

Though he could not see her eyes, her visible features were perfect and

her complexion was without flaw. Her hair was a gleaming chestnut and he

liked the way she used her hands. He believed in the test of hands as a

revelation of the mind. Her figure—what was the word? Mr Harlow pursed

his lips. His was a cold and exact vocabulary, lacking in floweriness.

‘Gracious,’ perhaps. He pursed his lips again. Yes, gracious—though why

it should be gracious… He found himself wandering down into the roots of

language, and even as he speculated she raised her head slightly and

looked at him. In profile she was pleasing enough, but now—

‘She is beautiful,’ agreed Stratford Harlow with himself, ‘but in all

probability she has a voice that would drive a man insane.’

Nevertheless, he determined to risk disillusionment. His interest in her

was impersonal. Two women, one young, one old, had played important parts

in his life; but he could think of women unprejudiced by his experience.

He neither liked nor disliked them, any more than he liked or disliked

the Farnese vase, which could be admired but had no special utility.

Presently the waiter came to take away his plate. ‘Miss Rivers,’ said the

waiter in a low voice, in answer to his query. ‘The young lady came this

morning and she’s going back to Plymouth by the last train. She’s here to

see somebody.’ He glanced significantly at Mr Harlow, who raised his

bushy eyebrows.

‘Inside?’ he asked, in a low voice.

The waiter nodded. ‘Her uncle—Arthur Ingle, the actor chap.’

Mr Harlow nodded. The name was dimly familiar. Ingle?… Nosegay with a

flower drooping out… and a judge with a cold in his head.

He began to reconstruct from his association of ideas.

He had been in court at the Old Bailey and seen the nosegay which every

judge carries—a practice which had its beginning in olden times, when a

bunch of herbs was supposed to shield his lordship from the taint of

Newgate fever. As the judge had laid the nosegay on the ledge three

little pimpernels in the centre had fallen on to the head of the clerk.

Now he remembered! Ingle! An ascetic face distorted with fury. Ingle, the

actor, who had forged and swindled, and had at last been caught. Mr

Stratford Harlow laughed softly; he not only remembered the name but the

man, and he had seen him that morning, scowling, and shrugging one

shoulder as he slouched past in the field gang So that was Ingle! And he

was an actor.

Mr Harlow had come back especially to Princetown to find out who he was.

As he looked up he saw the girl walking quickly from the room and,

rising, he strolled out after her, to find the lounge empty. Selecting

the most secluded corner, he rang for his coffee and lit a cigar.

Presently Ellenbury came in, but for the moment Mr Harlow had other

interests. Through the window he saw Miss Rivers walking across the

square in the direction of the post office and, rising, he strolled out

of the hotel and followed. She was buying stamps when he entered, and it

was pleasing to discover that her voice had all the qualities he could

desire.

Forty-eight has certain privileges; and can find the openings which would

lead to twenty-eight’s eternal confusion.

‘Good morning, young lady. You’re a fellow guest of ours, aren’t you?’

He said this with a smile which could be construed as fatherly. She shot

a glance at him and her lips twitched. She was too ready to smile, he

thought, for this visitation of hers to be wholly sorrowful.

‘I lunched at the Duchy, yes, but I’m not staying here. It is a dreadful

little town!’

‘It has its beauty,’ protested Mr Harlow.

He dropped sixpence on the counter, took up a local timetable, waited

while the girl’s change was counted and fell in beside her as they came

out of the office.

‘And romance,’ he added. ‘Take the Feathers Inn. There’s a building put

up by the labour of French prisoners of war.’

From where they stood only the top of one of the high chimneys of the

prison was visible.

She saw him glance in that direction and shake his head.

‘The other place, of course, is dreadful-dreadful! I’ve been trying to

work up my courage to go inside, but somehow I can’t.’

‘Have you—’ She did not finish the question.

‘A friend—yes. A very dear friend he was, many years ago, but the poor

fellow couldn’t go straight. I half promised to visit him, but I dreaded

the experience.’

Mr Harlow had no friend in any prison.

She looked at him thoughtfully.

‘It isn’t really so dreadful. I’ve been before,’ she said, without the

slightest embarrassment. ‘My uncle is there.’

‘Really?’ His voice had just the right quantity of sympathy and

understanding.

‘This is my second visit in four years. I hate it, of course, and I’ll be

glad when it’s over. It is usually rather—trying.’

They were pacing slowly towards the hotel now.

‘Naturally it is very dreadful for you. You feel so sorry for the poor

fellows—’

She was smiling; he was almost shocked.

‘That doesn’t distress me very much. I suppose it’s a brutal thing to

say, but it doesn’t. There is no’—she hesitated—‘there is no affection

between my uncle and myself, but I’m his only relative and I look after

his affairs’—again she seemed at a loss as to how she would

explain—‘and whatever money he has. And he’s rather difficult to

please.’

Mr Harlow was intensely interested; this was an aspect of the

Comments (0)