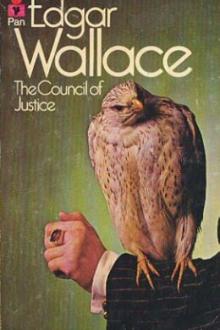

The Council of Justice by Edgar Wallace (simple e reader txt) 📕

So the Woman of Gratz arrived, and they talked about her and circulated her speeches in every language. And she grew. The hollow face of this lank girl filled, and the flat bosom rounded and there came softer lines and curves to her angular figure, and, almost before they realized the fact, she was beautiful.

So her fame had grown until her father died and she went to Russia. Then came a series of outrages which may be categorically and briefly set forth:--

1: General Maloff shot dead by an unknown woman in his private room at the Police Bureau, Moscow.

2: Prince Hazallarkoff shot dead by an unknown woman in the streets of Petrograd.

3: Colonel Kaverdavskov killed by a bomb thrown by a woman who made her escape.

And the Woman of Grat

Read free book «The Council of Justice by Edgar Wallace (simple e reader txt) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Edgar Wallace

- Performer: -

Read book online «The Council of Justice by Edgar Wallace (simple e reader txt) 📕». Author - Edgar Wallace

intruder, standing motionless in the doorway, could see nothing but

the shadowy figures of the inmates.

As he waited he was joined by three others, and he spoke rapidly in

a language that Starque, himself no mean linguist, could not

understand. One of his companions opened the door of the student’s room

and brought out something that he handed to the watcher on the

threshold.

Then the man entered the room alone and closed the door behind him,

not quite close, for he had trailed what looked like a thick cord

behind him and this prevented the shutting of the door.

Starque found his voice.

‘What do you want?’ he asked, quietly.

‘I want Bartholomew, who came into this room half an hour ago,’

replied the intruder.

‘He has left,’ said Starque, and in the darkness he felt at his feet

for the dead man—he needed the knife.

‘That is a lie,’ said the stranger coolly; ‘neither he nor you,

Rudolph Starque, nor the Woman of Gratz, nor the murderer Francois has

left.’

‘Monsieur knows too much,’ said Starque evenly, and lurched forward,

swinging his knife.

‘Keep your distance,’ warned the stranger, and at that moment

Starque and the silent Francois sprang forward and struck…

The exquisite agony of the shock that met them paralysed them for

the moment. The sprayed threads of the ‘live’ wire the man held before

him like a shield jerked the knife from Starque’s hands, and he heard

Francois groan as he fell.

‘You are foolish,’ said the voice again, ‘and you, madame, do not

move, I beg—tell me what has become of Bartholomew.’

A silence, then:

‘He is dead,’ said the Woman of Gratz.

She heard the man move.

‘He was a traitor—so we killed him,’ she continued calmly enough.

‘What will you do—you, who stand as a self-constituted judge?’

He made no reply, and she heard the soft rustle of his fingers on

the wall.

‘You are seeking the light—as we all seek it,’ she said, unmoved,

and she switched on the light.

He saw her standing near the body of the man she had lured to his

death, scornful, defiant, and strangely aloof from the sordidness of

the tragedy she had all but instigated.

She saw a tanned man of thirty-five, with deep, grave eyes, a broad

forehead, and a trim, pointed beard. A man of inches, with strength in

every line of his fine figure, and strength in every feature of his

face.

She stared at him insolently, uncaring, but before the mastery of

his eyes, she lowered her lids.

It seemed the other actors in the drama were so inconsiderate as to

be unworthy of notice. The dead man in his grotesque posture, the

unconscious murderer at his feet, and Starque, dazed and stunned,

crouching by the wall.

‘Here is the light you want,’ she went on, ‘not so easily do we of

the Red Hundred illuminate the gloom of despair and oppression—’

‘Spare me your speech-making,’ said Manfred coldly, and the scorn in

his voice struck her like the lash of a whip. For the first time the

colour came to her face and her eyes lit with anger.

‘You have bad counsellors,’ Manfred went on, ‘you, who talk of

autocrats and corrupt kingship—what are you but a puppet living on

flattery? It is your whim that you should be regarded as a conspirator

—a Corday. And when you are acclaimed Princess Revolutionary, it is

satisfactory to your vanity—more satisfactory than your title to be

hailed Princess Beautiful.’

He chose his words nicely.

‘Yet men—such men as these,’ he indicated Starque, ‘think only of

the Princess Beautiful—not the lady of the Inspiring Platitudes; not

the frail, heroic Patriot of the Flaming Words, but the warm flesh and

blood woman, lovable and adorable.’

He spoke in German, and there were finer shades of meaning in his

speech than can be exactly or literally translated. He spoke of a

purpose, evenly and without emotion. He intended to wound, and wound

deeply, and he knew he had succeeded.

He saw the rapid rise and fall of her bosom as she strove to regain

control of herself, and he saw, too, the blood on her lips where her

sharp white teeth bit.

‘I shall know you again,’ she said with an intensity of passion that

made her voice tremble. ‘I shall look for you and find you, and be it

the Princess Revolutionary or the Princess Beautiful who brings about

your punishment, be sure I shall strike hard.’

He bowed.

‘That is as it may be,’ he said calmly; ‘for the moment you are

powerless, if I willed it you would be powerless forever—for the

moment it is my wish that you should go.’

He stepped aside and opened the door.

The magnetism in his eyes drew her forward.

‘There is your road,’ he said when she hesitated. She was helpless;

the humiliation was maddening.

‘My friends—’ she began, as she hesitated on the threshold.

‘Your friends will meet the fate that one day awaits you,’ he said

calmly.

White with passion, she turned on him.

‘You!—threaten me! a brave man indeed to threaten a woman!’

She could have bitten her tongue at the slip she made. She as a

woman had appealed to him as a man! This was the greatest humiliation

of all.

There is your road,’ he said again, courteously but

uncompromisingly.

She was scarcely a foot from him, and she turned and faced him, her

lips parted and the black devil of hate in her eyes.

‘One day—one day,’ she gasped, ‘I will repay you!’ Then she turned

quickly and disappeared through the door, and Manfred waited until her

footsteps had died away before he stooped to the half-conscious Starque

and jerked him to his feet.

CHAPTER VII. The Government and Mr. Jessen

In recording the events that followed the reappearance of the Four

Just Men, I have confined myself to those which I know to have been the

direct outcome of the Red Hundred propaganda and the counter-activity

of the Four Just Men.

Thus I make no reference to the explosion at Woolwich Arsenal, which

was credited to the Red Hundred, knowing, as I do, that the calamity

was due to the carelessness of a workman. Nor to the blowing up of the

main in Oxford Street, which was a much more simple explanation than

the fantastic theories of the Megaphone would have you imagine.

This was not the first time that a fused wire and a leaking gas main

brought about the upheaval of a public thoroughfare, and the elaborate

plot with which organized anarchy was credited was without

existence.

I think the most conscientiously accurate history of the Red Hundred

movement is that set forth in the series of ten articles contributed to

the Morning Leader by Harold Ashton under the title of ‘Forty

Days of Terrorism’, and, whilst I think the author frequently fails

from lack of sympathy for the Four Just Men to thoroughly appreciate

the single-mindedness of this extraordinary band of men, yet I shall

always regard ‘Forty Days of Terrorism’ as being the standard history

of the movement, and its failure.

On one point in the history alone I find myself in opposition to Mr.

Ashton, and that is the exact connection between the discovery of the

Carlby Mansion Tragedy, and the extraordinary return of Mr. Jessen of

37 Presley Street.

It is perhaps indiscreet of me to refer at so early a stage to this

return of Jessen’s, because whilst taking exception to the theories put

forward in ‘Forty Days of Terrorism’, I am not prepared to go into the

evidence on which I base my theories.

The popular story is that one morning Mr. Jessen walked out of his

house and demanded from the astonished milkman why he had omitted to

leave his morning supply. Remembering that the disappearance of

‘Long’—perhaps it would be less confusing to call him the name by

which he was known in Presley Street—had created an extraordinary

sensation; that pictures of his house and the interior of his house had

appeared in all the newspapers; that the newspaper crime experts had

published columns upon columns of speculative theories, and that 37

Presley Street, had for some weeks been the Mecca of the morbid minded,

who, standing outside, stared the unpretentious facade out of

countenance for hours on end; you may imagine that the milkman legend

had the exact journalistic touch that would appeal to a public whose

minds had been trained by generations of magazine-story writers to just

such denouement as this.

The truth is that Mr. Long, upon coming to life, went immediately to

the Home Office and told his story to the Under Secretary. He did not

drive up in a taxi, nor was he lifted out in a state of exhaustion as

one newspaper had erroneously had it, but he arrived on the top of a

motor omnibus which passed the door, and was ushered into the Presence

almost at once. When Mr. Long had told his story he was taken to the

Home Secretary himself, and the chief commissioner was sent for, and

came hurriedly from Scotland Yard, accompanied by Superintendent

Falmouth. All this is made clear in Mr. Ashton’s book.

‘For some extraordinary reason,’ I quote the same authority, ‘Long,

or Jessen, seems by means of documents in his possession to have

explained to the satisfaction of the Home Secretary and the Police

Authorities his own position in the matter, and moreover to have

inspired the right hon. gentleman with these mysterious documents, that

Mr. Ridgeway, so far from accepting the resignation that Jessen placed

in his hands, reinstated him in his position.’

As to how two of these documents came to Jessen or to the Four Just

Men, Mr. Ashton is very wisely silent, not attempting to solve a

mystery which puzzled both the Quai d’Orsay and Petrograd.

For these two official forms, signed in the one case by the French

President and in the other with the sprawling signature of Czar

Nicholas, were supposed to be incorporated with other official

memoranda in well-guarded national archives.

It was subsequent to Mr. Jessen’s visit to the Home Office that the

discovery of the Garlby Mansions Tragedy was made, and I cannot do

better than quote The Times, since that journal, jealous of the

appearance in its columns of any news of a sensational character,

reduced the intelligence to its most constricted limits. Perhaps

the Megaphone account might make better reading, but the space at

my disposal will not allow of the inclusion in this book of the

thirty-three columns of reading matter, headlines, portraits, and

diagrammatic illustrations with which that enterprising journal served

up particulars of the grisly horror to its readers. Thus, The

Times:—

Shortly after one o’clock yesterday afternoon and in consequence of

information received, Superintendent Falmouth, of the Criminal

Investigation Department, accompanied by Detective-Sergeants Boyle and

Lawley, effected an entrance into No. 69, Carlby Mansions, occupied by

the Countess Slienvitch, a young Russian lady of independent means.

Lying on the floor were the bodies of three men who have since been

identified as—

Lauder Bartholomew, aged 33, late of the Koondorp Mounted

Rifles;

Rudolph Starque, aged 40, believed to be an Austrian and a prominent

revolutionary propagandist;

Henri Delaye Francois, aged 36, a Frenchman, also believed to have

been engaged in propaganda work.

The cause of death in the case of Bartholomew seems to be evident,

but with the other two men some doubt exists, and the police, who

preserve an attitude of rigid reticence,

Comments (0)