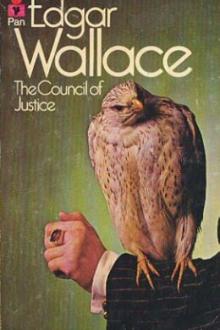

The Council of Justice by Edgar Wallace (simple e reader txt) 📕

So the Woman of Gratz arrived, and they talked about her and circulated her speeches in every language. And she grew. The hollow face of this lank girl filled, and the flat bosom rounded and there came softer lines and curves to her angular figure, and, almost before they realized the fact, she was beautiful.

So her fame had grown until her father died and she went to Russia. Then came a series of outrages which may be categorically and briefly set forth:--

1: General Maloff shot dead by an unknown woman in his private room at the Police Bureau, Moscow.

2: Prince Hazallarkoff shot dead by an unknown woman in the streets of Petrograd.

3: Colonel Kaverdavskov killed by a bomb thrown by a woman who made her escape.

And the Woman of Grat

Read free book «The Council of Justice by Edgar Wallace (simple e reader txt) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Edgar Wallace

- Performer: -

Read book online «The Council of Justice by Edgar Wallace (simple e reader txt) 📕». Author - Edgar Wallace

He dipped his hand into his overcoat pocket and drew forth the

machine. It was one of Culveri’s masterpieces and, to an extent,

experimental—that much the master had warned him in a letter that bore

the date-mark ‘Riga’. He felt with his thumb for the tiny key that

‘set’ the machine and pushed it.

Then he slipped into the doorway of No. 196 and placed the bomb. It

was done in a second, and so far as he could tell no man had seen him

leave the pathway and he was back again on the sidewalk very quickly.

But as he stepped back, he heard a shout and a man darted across the

road, calling on him to surrender. From the left two men were running,

and he saw the man in evening dress blowing a whistle.

He was caught; he knew it. There was a chance of escape—the other

end of the street was clear—he turned and ran like the wind. He could

hear his pursuers pattering along behind him. His ear, alert to every

phase of the chase, heard one pair of feet check and spring up the

steps of 196. He glanced round. They were gaining on him, and he turned

suddenly and fired three times. Somebody fell; he saw that much. Then

right ahead of him a tall policeman sprang from the shadows and clasped

him round the waist.

‘Hold that man!’ shouted Falmouth, running up. Blowing hard came the

night wanderer, a ragged object but skilful, and he had Von Dunop

handcuffed in a trice.

It was he who noticed the limpness of the prisoner.

‘Hullo!’ he said, then held out his hand. ‘Show a light here.’

There were half a dozen policemen and the inevitable crowd on the

spot by now, and the rays of the bull’s-eye focused on the detective’s

hand. It was red with blood. Falmouth seized a lantern and flashed it

on the man’s face.

There was no need to look farther. He was dead,—dead with the

inevitable label affixed to the handle of the knife that killed

him.

Falmouth rapped out an oath.

‘It is incredible; it is impossible! he was running till the

constable caught him, and he has not been out of our hands! Where is

the officer who held him?’

Nobody answered, certainly not the tall policeman, who was at that

moment being driven eastward, making a rapid change into the

conventional evening costume of an English gentleman.

CHAPTER X. The Trial

To fathom the mind of the Woman of Gratz is no easy task, and one

not to be lightly undertaken. Remembering her obscure beginning, the

bare-legged child drinking in revolutionary talk in the Transylvanian

kitchen, and the development of her intellect along unconventional

lines—remembering, also, that early in life she made acquaintance with

the extreme problems of life and death in their least attractive forms,

and that the proportion of things had been grossly distorted by her

teachers, you may arrive at a point where your vacillating judgement

hesitates between blame and pity.

I would believe that the power of introspection had no real place in

her mental equipment, else how can we explain her attitude towards the

man whom she had once defied and reconcile those outbursts of hers

wherein she called for his death, for his terrible punishment, wherein,

too, she allowed herself the rare luxury of unrestrained speech, how

can we reconcile these tantrums with the fact that this man’s voice

filled her thoughts day and night, the recollection of this man’s eyes

through his mask followed her every movement, till the image of him

became an obsession?

It may be that I have no knowledge of women and their ways (there is

no subtle smugness in the doubt I express) and that her inconsistency

was general to her sex. It must not be imagined that she had spared

either trouble or money to secure the extermination of her enemies, and

the enemies of the Red Hundred. She had described them, as well as she

could, after her first meeting, and the sketches made under her

instruction had been circulated by the officers of the Reds.

Sitting near the window of her house, she mused, lulled by the

ceaseless hum of traffic in the street below, and half dozing.

The turning of the door-handle woke her from her dreams.

It was Schmidt, the unspeakable Schmidt, all perspiration and

excitement. His round coarse face glowed with it, and he could scarcely

bring his voice to tell the news.

‘We have him! we have him!’ he cried in glee, and snapped his

fingers. ‘Oh, the good news!—I am the first! Nobody has been, Little

Friend? I have run and have taken taxis—’

‘You have—whom?’ she asked.

‘The man—one of the men’ he said, ‘who killed Starque and Francois,

and—’

‘Which—which man?’ she said harshly.

He fumbled in his pocket and pulled out a discoloured sketch.

‘Oh!’ she said, it could not be the man whom she had defied, ‘Why,

why?’ she asked stormily, ‘Why only this man? Why not the others—why

not the leader?—have they caught him and lost him?’

Chagrin and astonishment sat on Schmidt’s round face. His

disappointment was almost comic.

‘But, Little Mother!’ he said, crestfallen and bewildered, ‘this is

one—we did not hope even for one and—’

The storm passed over.

‘Yes, yes,’ she said wearily, ‘one—even one is good. They shall

learn that the Red Hundred can still strike—this leader shall know

—This man shall have a death,’ she said, looking at Schmidt ‘worthy of

his importance. Tell me how he was captured.’

‘It was the picture,’ said the eager Schmidt, ‘the picture you had

drawn. One of our comrades thought he recognized him and followed him

to his house.’

‘He shall be tried—tonight,’ and she spent the day anticipating her

triumph.

Conspirators do not always choose dark arches for their plottings.

The Red Hundred especially were notorious for the likeliness of their

rendezvous. They went to nature for a precedent, and as she endows the

tiger with stripes that are undistinguishable from the jungle grass, so

the Red Hundred would choose for their meetings such a place where

meetings were usually held.

It was in the Lodge Room of the Pride of Millwall, AOSA—which may

be amplified as the Associated Order of the Sons of Abstinence—that

the trial took place. The financial position of the Pride of Millwall

was not strong. An unusual epidemic of temperate seafaring men had

called the Lodge into being, the influx of capital from eccentric

bequests had built the tiny hall, and since the fiasco attending the

first meeting of the League of London, much of its public business had

been skilfully conducted in these riverside premises. It had been

raided by the police during the days of terror, but nothing of an

incriminating character had been discovered. Because of the success

with which the open policy had been pursued the Woman of Gratz

preferred to take the risk of an open trial in a hall liable to police

raid.

The man must be so guarded that escape was impossible. Messengers

sped in every direction to carry out her instruction. There was a rapid

summoning of leaders of the movement, the choice of the place of trial,

the preparation for a ceremony which was governed by well-established

precedent, and the arrangement of the properties which played so

effective a part in the trials of the Hundred.

In the black-draped chamber of trial the Woman of Gratz found a full

company. Maliscrivona, Tchezki, Vellantini, De Romans, to name a few

who were there sitting altogether side by side on the low forms, and

they buzzed a welcome as she walked into the room and took her seat at

the higher place. She glanced round the faces, bestowing a nod here and

a glance of recognition there. She remembered the last time she had

made an appearance before the rank and file of the movement. She missed

many faces that had turned to her in those days: Starque, Francois,

Kitsinger—dead at the hands of the Four Just Men. It fitted her mood

to remember that tonight she would judge one who had at least helped in

the slaying of Starque.

Abruptly she rose. Lately she had had few opportunities for the

display of that oratory which was once her sole title to consideration

in the councils of the Red Hundred. Her powers of organization had come

to be respected later. She felt the want of practice as she began

speaking. She found herself hesitating for words, and once she felt her

illustrations were crude. But she gathered confidence as she proceeded

and she felt the responsive thrill of a fascinated audience.

It was the story of the campaign that she told. Much of it we know;

the story from the point of view of the Reds may be guessed. She

finished her speech by recounting the capture of the enemy.

‘Tonight we aim a blow at these enemies of progress; if they have

been merciless, let us show them that the Red Hundred is not to be

outdone in ferocity. As they struck, so let us strike—and, in

striking, read a lesson to the men who killed our comrades, that they,

nor the world, will ever forget.’

There was no cheering as she finished—that had been the order—but

a hum of words as they flung their tributes of words at her feet—a

ruck of incoherent phrases of praise and adoration.

Then two men led in the prisoner.

He was calm and interested, throwing out his square chin resolutely

when the first words of the charge were called and twiddling the

fingers of his bound hands absently.

He met the scowling faces turned to him serenely, but as they

proceeded with the indictment, he grew attentive, bending his head to

catch the words.

Once he interrupted.

‘I cannot quite understand that,’ he said in fluent Russian, ‘my

knowledge of German is limited.’

‘What is your nationality?’ demanded the woman.

‘English,’ he replied.

‘Do you speak French?’ she asked.

‘I am learning,’ he said naively, and smiled.

‘You speak Russian,’ she said. Her conversation was carried on in

that tongue.

‘Yes,’ he said simply; ‘I was there for many years.’

After this, the sum of his transgressions were pronounced in a

language he understood. Once or twice as the reader proceeded—it was

Ivan Oranvitch who read—the man smiled.

The Woman of Gratz recognized him instantly as the fourth of the

party that gathered about her door the day Bartholomew was murdered.

Formally she asked him what he had to say before he was condemned.

He smiled again.

‘I am not one of the Four Just Men,’ he said; ‘whoever says I am—

lies.’

‘And is that all you have to say?’ she asked scornfully.

‘That is all,’ was his calm reply.

‘Do you deny that you helped slay our comrade Starque?’

‘I do not deny it,’ he said easily, ‘I did not help—I killed

him.’

‘Ah!’ the exclamation came simultaneously from every throat.

‘Do you deny that you have killed many of the Red Hundred?’

He paused before he answered.

‘As to the Red Hundred—I do not know; but I have killed many

people.’ He spoke with the grave air of a man filled with a sense of

responsibility, and again the exclamatory hum ran through the hall.

Yet, the Woman of Gratz had a growing sense of unrest in spite of the

success of the examination.

‘You have said you were in Russia—did men fall to your hand

there?’

He nodded.

Comments (0)