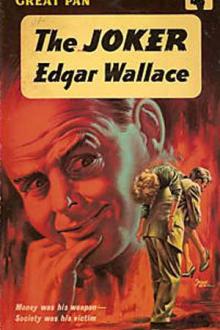

The Joker by Edgar Wallace (best inspirational books .txt) 📕

'I don't know,' said the older man vaguely. 'One could travel... '

'The English people have two ideas of happiness: one comes from travel, one from staying still! Rushing or rusting! I might marry but I don't wish to marry. I might have a great stable of race-horses, but I detest racing. I might yacht--I loathe the sea. Suppose I want a thrill? I do! The art of living is the art of victory. Make a note of that. Where is happiness in cards, horses, golf, women-anything you like? I'll tell you: in beating the best man to it! That's An Americanism. Where is the joy of mountain climbing, of exploration, of scientific discovery? To do better than somebody else--to go farther, to put your foot on the head of the next best.'

He blew a cloud of smoke through the open window and waited until the breeze had torn the misty gossamer into shreds and nothingness.

'When you're a millionaire you either

Read free book «The Joker by Edgar Wallace (best inspirational books .txt) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Edgar Wallace

- Performer: -

Read book online «The Joker by Edgar Wallace (best inspirational books .txt) 📕». Author - Edgar Wallace

deal of difficulty, and, running down the index to discover if she had

missed any further reference, her finger stopped at the words:

‘Harlow—Mercy Mildred.

Harlow-Stratford Selwyn Mortimer.’

She would not have been human if she had not turned up the pages. For a

quarter of an hour she pored over the accounts of the dead and gone Miss

Mercy, that stern and eccentric woman, and then she saw an item ‘To L.

Edwins, �125.’ An entry occurred four months later: ‘To L. Edwins, �183

17s. 4d.’ She knew of Mrs Edwins, and had seen a copy of Miss Mercy

Harlow’s will—she had looked it up after the Dartmoor meeting, being

momentarily interested in the millionaire.

She turned to Stratford’s account, which was a very small one. Evidently,

Mr Harlow made no payments through his lawyers. If an opportunity had

occurred she would have asked Mr Stebbings for further information about

the family, though she was fairly sure that such a request would have

produced no satisfactory result.

Deprived of this interest, Aileen was thrown back upon the dominating

occupation of life—her amazement and disapproval of Aileen Rivers in

relation to Mr James Carlton.

He knew her address: she had particularly told him the number. Equally

true it was that she had asked him only to write on official business. By

some miracle she had not been called to give evidence at the inquest and

she might, and did, trace his influence here. But even that could not be

set against a week’s neglect.

‘Ridiculous’ (said the saner part other, in tones of reprobation). ‘You

hardly know the man! Just because he’s been civil to you and has taken

you out to dinner twice (and they were both more or less business

occasions), you’re expecting him to behave as though he were engaged to

you!’

The unregenerate Aileen Rivers merely tossed her head at this and was

unashamed.

She could, of course, have written to him: there was excuse enough; and

she actually did begin a letter, until the scandalous character of her

behaviour grew apparent even to Aileen II.

Saturday passed and Sunday; she stayed at home both days in case—

He called on Sunday night, when she had given up—well, if not hope, at

any rate expectation.

‘I’ve been down to the country,’ he said.

She interviewed him in the sitting room, which her landlady set aside for

formal calls.

‘Couldn’t you come out somewhere? Have you dined?’

She had dined.

‘Come along and walk; it’s rather a nice night. We can have coffee

somewhere.’

Her duty was to tell him that he was taking much for granted, but she

didn’t. She went upstairs, got her coat and in the shortest space of time

was walking with him through Bloomsbury Square.

‘I’m rather worried about you,’ he said.

‘Are you?’ Her surprise was genuine.

Yes, I am a little. Didn’t you tell me Mrs Gibbins used to confide her

troubles to you?’ There was a note of anxiety in his voice.

‘She was rather confidential at times.’

‘Did she ever tell you anything about her past?’

‘Oh, no,’ said Aileen quickly. ‘It was mostly about her mother, who died

about four years ago.’

‘Did she ever tell you her Christian name—her mother’s, I mean?’

‘Louisa,’ answered the girl promptly. ‘You’re awfully mysterious, Mr

James Carlton. What has this to do with poor Mrs Gibbins?’

‘Nothing, except that her name was Annie Maud, and the letters containing

the money, which came to her quarterly, were addressed to “Louisa,” 14

Kennet Road, Birmingham, and readdressed by the postal authorities. A

letter came this morning.’

‘Poor soul!’ said the girl softly.

‘Yes.’

It was surprising how well she understood him, remembering the shortness

of their acquaintance. She knew, for example, when he was thinking of

something else—his voice rose half a tone.

‘Isn’t that strange? Do you remember my telling you of the eighteen

thousand policemen and the Brigade of Guards, and the whole congregation

of the blessed? And now they are all agitated because Mrs Gibbins’s

mother was named Louisa! That discovery—I shouldn’t have asked you,

because I knew it already—proved two things: first, that Mrs Gibbins

committed a crime some fifteen years ago, and secondly, that this is the

second time she’s been dead!’

He suddenly relaxed and laughed softly.

‘Don’t tell me,’ he warned her. ‘I know just the fictional detective whom

I am imitating! The whole thing is rather complicated. Did I say coffee

or dinner?’

‘You said coffee,’ she said.

The popular restaurant into which they went was just a little overcrowded

and after being served they lost no time in making their escape.

They were passing along Coventry Street when a big car rolled slowly

past. The man who was driving was in evening dress… they saw the sheen

of his diamond studs, the red tip of his cigar.

‘Nobody on earth but the Splendid Harlow could so scintillate,’ said Jim.

‘What does he do in this part of the world at such an hour?’

The car turned to the right through Leicester Square and passed down

Orange Street at a pace which was strangely majestic. It was as though it

formed part of and led a magnificent procession. The same thought

occurred to both of them.

‘He should really travel with a band!’

‘I was thinking that, too,’ laughed the girl. ‘He frightened me terribly

the night he came to the flat. I mean, when I opened the door to him. And

I’m not easily scared. He looked so big and powerful and ruthless that my

soul cowered before him!’

They passed up deserted Long Acre; it was too early for the market carts

to have assembled, and the street was a wilderness. Suddenly the girl

found her hand held loosely in Jim Carlton’s. He was swinging it to and

fro. The severer side of Miss Aileen Rivers closed its eyes and pretended

not to see.

‘I’ve got a very friendly feeling for you,’ said Jim huskily. ‘I don’t

know why, but I just have. And if you talk about the philandering

constabulary, I will never forgive you.’

Three men had suddenly debouched from a side street; they were talking

noisily and violently and were moving slowly towards them. Jim looked

round: the only man in sight was walking in the opposite direction,

having passed them a minute or so before.

‘I think we’ll cross the road,’ he said. He took her arm, and, quickening

his step, led her to the opposite sidewalk.

The quarrelling three turned back and Jim stopped. ‘I want you to run

back to the other end of Long Acre and fetch a policeman,’ he said in a

low voice. ‘Will you do this for me? Run!’

Obediently she turned and fled, and as she did so one of the three came

lurching towards him.

‘What’s the idea?’ he said loudly. ‘Can’t we have an argument without you

butting in?’

‘Stay where you are, Donovan,’ said Jim. ‘I know you and I know just what

you’re after.’

‘Get him,’ said somebody angrily, and Jim Carlton whipped out the twelve

inch length of jambok that he carried in his pocket and struck at the

nearest man. As the flexible hide reached its billet the man dropped like

one shot. In another second his two companions had sprung at the

detective; and he knew that he was fighting, if not for his life, at any

rate to save himself from an injury which would incapacitate him for

months.

Again the jambok reached home; a second man reeled.

And then a taxicab came flying down Long Acre with a policeman on each

footboard…

‘No, not Bow Street,’ said Jim, ‘take them to Cannon Row.’

Aileen was in the taxicab, a most unheroic woman, on the verge of tears.

‘I guessed what they were after,’ said Jim, as they were driving home.

‘It is one of the oldest tricks in the world, that rehearsed street

fight.’

‘But why? Why did they do it? Were they old enemies of yours?’ she asked,

bewildered.

‘One,’ he said. ‘Donovan.’ He carefully avoided her second question.

The presence of Mr Harlow in his lordly car was no accident. The car

which passed down Orange Street was ostensibly carrying him to Vira’s

Club, but there was a short cut which brought him through St Martin’s

Lane to the end of Long Acre before the two walkers could possibly reach

there. What was more important was that it was very clear to Jim that he

and the girl were under observation, and had been followed that night

from the moment he left the club where he lived, until the attack was

delivered.

The reason for the hold-up was not difficult to understand, even

supposing he ruled out the very remote possibility that it was associated

with Mrs Gibbins’s death. And that he must exclude, unless he gave Mr

Harlow credit for supernatural powers.

He saw the girl to her boarding house and went back to Scotland Yard, to

find a telegram awaiting him. It was from the detective force of

Birmingham, and ran:

‘Your inquiry 793 Mrs Louisa Gibbins, deceased. Letter which came to her

regularly every quarter, and which was subsequently readdressed to Mrs

Gibbins, of Stanmore Rents, Lambeth, invariably had Norwood postmark.

This fact verified by lodger of late Mrs Gibbins of this town. Annie Maud

Gibbins’s real name, Smith. She married William Smith, a platelayer on

Midland Railway. Further details follow, Hooge. Ends.’

A great deal of this information was not new to Jim Carlton. But the

Norwood postmark was invaluable, for in that suburb of London lived Mr

Ellenbury. Further details he would not need.

But before that clue could be followed, Jim Carlton’s attention was

wholly occupied by the strange behaviour of Arthur Ingle, who suddenly

turned recluse, declined all communication with the outside world and,

locking himself in his flat, gave himself to the study of cinematography.

IN THE days which followed Jim Carlton was a busy man, and only once

during the week did he find time to see Aileen, and then she related one

of the minor troubles of life.

A new boarder had come to the establishment where she lived, an athletic

young man who occupied the room immediately beneath hers and whose

apparent admiration took the form of following tier to her work every

morning at a respectful distance.

‘I wouldn’t mind that, but he makes a point of being in the neighbourhood

of the office when I come out for lunch, and when I go home at nights.’

‘Has he spoken to you?’ asked Jim, interested.

‘Oh, no, he’s been most correct; he doesn’t even speak at meals.’

‘Bear with him,’ said Jim, a twinkle in his eye. ‘It is one of the

penalties attached to the moderately good-looking.’

Jim interviewed the girl’s new admirer.

‘As a shadow you’re a little on the heavy side, Brown,’ he said. ‘You

should have found a way of watching her without her knowing.’

‘I’m very sorry, sir,’ said Detective Brown, and thereafter his espionage

was less oppressive.

It was remarkable that in none of the excursions which Jim Carlton made

from day to day did he once see Arthur Ingle. Deliberately he called at

those restaurants and places of resort which in the old days were

favoured by the man. It would not be a sense of shame or an unwillingness

to meet old friends and associates of a more

Comments (0)