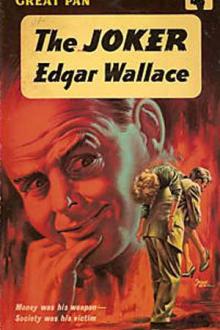

The Joker by Edgar Wallace (best inspirational books .txt) 📕

'I don't know,' said the older man vaguely. 'One could travel... '

'The English people have two ideas of happiness: one comes from travel, one from staying still! Rushing or rusting! I might marry but I don't wish to marry. I might have a great stable of race-horses, but I detest racing. I might yacht--I loathe the sea. Suppose I want a thrill? I do! The art of living is the art of victory. Make a note of that. Where is happiness in cards, horses, golf, women-anything you like? I'll tell you: in beating the best man to it! That's An Americanism. Where is the joy of mountain climbing, of exploration, of scientific discovery? To do better than somebody else--to go farther, to put your foot on the head of the next best.'

He blew a cloud of smoke through the open window and waited until the breeze had torn the misty gossamer into shreds and nothingness.

'When you're a millionaire you either

Read free book «The Joker by Edgar Wallace (best inspirational books .txt) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Edgar Wallace

- Performer: -

Read book online «The Joker by Edgar Wallace (best inspirational books .txt) 📕». Author - Edgar Wallace

did not. I do not carry arms. I regard any man who resists arrest by the

use of weapons as a cowardly barbarian! For the police have their

duties—very painful duties sometimes, pleasant duties at others—I am

not quite sure in which category yours will fall.’

Elk opened the car door and Mr Harlow stepped in, settled himself

comfortably in the corner and asked: ‘May I smoke?’

He produced a cigar from his coat pocket and Elk held the light as the

car moved towards Evory Street.

‘There is one thing I would like to ask you, Carlton,’ he said,

half-turning his head towards his captor, who sat by his side. ‘I read in

the newspapers that the ports and airports were being watched and all

sorts of extraordinary precautions were being taken against my leaving

the country. I presume that the news of my arrest will be made known

immediately to these watchful gentlemen? I should hate to feel that they

were tramping up and down in the cold, looking for a man who was already

in custody. That would spoil my night’s sleep.’

Jim humoured his mood. ‘They will be notified,’ he said.

‘You found Marling, of course? He has suffered no injury? I am very

relieved. It is difficult to conceive the confusion which must arise in

the mind of a man who has been out of the world for some twenty years and

returns to find the streets so crowded with death-dealing automobiles,

driven usually at a pace beyond the legal limit.’

‘Yes, Mr Harlow is in good hands.’

‘Call him Marling,’ said the other. ‘And Marling he must remain until my

duplicity is proved beyond any question. I will make the matter easy for

you by admitting that he is Stratford Selwyn Mortimer Harlow.’

He went off at a tangent, a trick of his.

‘I should have gone away a long time ago and defied you to bring home to

me any offence against the law. But I am intensely curious—if my dearest

wish were realised, I would be suspended in a condition of disembodied

consciousness to watch the progress of the world through the next two

hundred thousand years! I would like to see what new nations arise, what

new powers overspread the earth, what new continents will be pushed up

from the sea and old continents submerged! Two hundred thousand years.

There will be a new Rome, a new barbarian Britain, a new continent of

America populated by indescribable beings! New Ptolemys and Pharaohs

getting themselves embalmed; and never dreaming that their magnificent

tombs shall be buried under sand and forgotten until they are dug out to

be gaped at by tourists, who will pay two piastres a peep!’

He sighed, flicked the ash of his cigar onto the floor of the car. ‘Well,

here I am at the end. I’ve seen it out. I know now into which compartment

the little whirling ball of fate has fallen. It is extremely

interesting.’

They hurried him into the charge-room and put him in the steel pen; and

he beamed round the room.

In an undertone to Jim he said: ‘Can anything be done to prevent the

newspapers with one accord describing what they will call the “irony” of

my appearance in a police station which I presented to the nation? Almost

I am tempted to present a million pounds to the journal which refrains

from this obvious comment!’

He listened in silence to the charge which Elk read, interrupting only

once.

‘Suspected of causing the death of Mrs Gibbins? How perfectly absurd!

However, that is a matter for the lawyers to thrash out.’

With the jailer’s hand on his arm he disappeared to the cells.

‘And that’s that!’ said Jim, with a heartfelt sigh of relief.

‘Where’s the real fellow?’ asked Elk.

‘At the house in Park Lane. He’s got the whole story for us. I’ve

arranged to have a police stenographer at nine o’clock tonight.’

At nine o’clock the bearded man sat in Mr Harlow’s library; and began in

hesitant tones to tell his amazing story.

‘MY NAME is Stratford Selwyn Mortimer Harlow and as a child I lived as

you know with my aunt, Miss Mercy Harlow, a very rich and eccentric lady,

who assumed full charge of me and quarrelled with my other aunts over the

question of my care. I do not remember very distinctly the early days of

my life. I have an idea, which Marling confirms, that I was a backward

child—backward mentally, that is to say—and that my condition caused

the greatest anxiety to Miss Mercy, who lived in terror lest I became

feeble-minded and she was in some way held responsible by her sisters.

This fear became an obsession with her, and I was kept out of the way

whenever visitors called at the house, and practically saw nobody but

Miss Mercy, her maid Mrs Edwins, and her maid’s son Lemuel, who on two

occasions was, I believe, substituted for me—he being a very healthy

child.

‘I know nothing about the circumstances of his birth, but it is a fact

that he was never called by the name of Edwins, except by Miss Mercy, and

she continued to call him this even after the time came for him to go to

school and the production of his birth certificate made it necessary that

he should bear the name of his father, Marling.

‘He was my only playmate; and I think that he was genuinely fond of me

and that he pitied what he believed to be my weakness of intellect. Mrs

Edwins’ ambition for her son was unbounded; she strived and scraped to

send him to a public school, and when he got a little older (as he told

me himself) she prevailed upon Miss Mercy to give her the money to send

him to the university.

‘Let me say here that I owe most of my information on the subject to

Marling himself—it seems strange to call him by a name which I have

borne so long! At that time my mind was undoubtedly clouded. He has

described me as a morose, timid boy, who spent day after day in a

brooding silence, and I should say that that description was an accurate

one.

‘The fear that her relatives might discover my condition of mind was a

daily torment to Miss Mercy. She shut up her house and went to live at a

smaller house in the country; and whenever her sisters showed the

slightest inclination to visit her, she would move to a distant town. For

three years I saw very little of Marling, and then one day Miss Mercy

told me that she was engaging a tutor for me. I disliked the idea, but

when she said it was Marling I was overjoyed. He came to Bournemouth to

see us and I should not have known him, for he had grown a long golden

beard, of which he was very proud. We had long talks together and he told

me of some of his adventures and of the scrapes he had got into.

‘I was the only person in whom he confided, and I know the full story of

Mrs Gibbins as she was called. He had met her when she was a pretty

housemaid in the service of the senior proctor. The courtship followed a

tumultuous course, and then one day there arrived at Oxford the girl’s

mother, who threatened that unless Marling married her daughter, she

would inform the senior proctor. This threat, if it were carried out

meant ruin to him, the end of Miss Mercy’s patronage, the destruction of

all his mother’s hopes; and it was not surprising that he took the

easiest course. They were married secretly at Cheltenham and lived

together in a little village just outside the city of Oxford.

‘Of course the marriage was disastrous for Marling. He did not love the

girl; she hated him with all the malignity that a common and ignorant

person can have for one whose education emphasised her own uncouthness.

The upshot of it was that he left her. Three years later he learnt from

her mother that she was dead. In point of fact that was not true. She had

contracted a bigamous marriage with a man named Smith, who was eventually

killed in the war. You have told me, Mr Carlton, that you found no

marriage certificate in her handbag.

‘By this time, owing to circumstances which I will explain, Marling had

the handling of great wealth. He was oddly generous, but the pound a week

which he allowed his wife’s mother was, I suspect, in the nature of a

thanksgiving for freedom. The money came regularly to her every quarter

and while she suspected who the sender was, she had no proof and was

content to go on enjoying her allowance. Later this was improperly

diverted to her daughter, who, on the death of her mother, assumed her

maiden name.

‘Marling came to be my tutor, and I honestly think that in his care—I

would almost say affectionate guidance—I had improved in health, though

I was far from well, when Miss Mercy had her seizure. In my crazy despair

I remember I accused Marling of killing her, for I saw him pour the

contents of a green bottle into a glass and force it between Miss Mercy’s

pale lips. I am convinced that I did him a grave injustice, though he

never ceased to remind me of that green bottle. I think it was part of

his treatment to keep my illusion before my eyes until I recognised my

error.

‘On the death of Miss Mercy I was so ill that I had to be locked in my

room, and it was then, I think, that Mrs Edwins proposed the plan which

was afterwards adopted, namely, the substitution of Marling for myself.

You will be surprised and incredulous when I tell you that Marling never

forgave the woman for inducing him to take that step. He told me once

that she had put him into greater bondage than that in which I was held.

From his point of view I think he was sincere. I was hurried away to a

cottage in Berkshire; and I knew nothing of the substitution until months

afterwards, when I was brought to Park Lane. It was then that he told me

my name was Marling and that his was Harlow. He used to repeat this

almost like a lesson, until I became used to the change.

‘I don’t think I cared very much; I had a growing interest in books and

he was tireless in his efforts to interest me. He claimed, with truth,

that whatever imprisonment I suffered, he saved me from imbecility. The

quiet of the life, the carefree nature of it, the comfort and mental

satisfaction which it gave me, was the finest treatment I could have

possibly had. He made me acquainted with the pathological side of my

case, read me books that explained just why I was living the very best

possible life—again I say, he was sincere.

‘Gradually the cloud seemed to dissipate from my mind. I could think

logically and in sequence; I could understand what I was reading. More

and more the extent of the wrong he had done me became apparent. He never

disguised the fact, if the truth be told. Indeed, he disguised nothing!

He took me completely into his confidence. I knew every coup he

engineered in every detail.

‘One night he returned to the house terribly agitated, and told me that

he had heard the voice of his wife! He had been to

Comments (0)