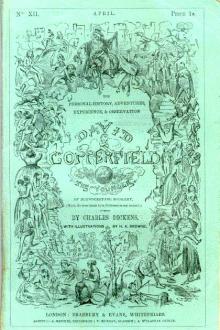

Tales from Dickens by Charles Dickens (books you need to read TXT) 📕

People have often wondered how Dickens found time to accomplish so many different things. One of the secrets of this, no doubt, was his love of order. He was the most systematic of men. Everything he did "went like clockwork," and he prided himself on his punctuality. He could not work in a room unless everything in it was in its proper place. As a consequence of this habit of regularity, he never wasted time.

The work of editorship was very pleasant to Dickens, and scarcely three years after his leaving the Daily News he began the publication of a new magazine which he called Household Words. His aim was to make it cheerful, useful and at the same time cheap, so that the poor could afford to buy it as well as the rich. His own sto

Read free book «Tales from Dickens by Charles Dickens (books you need to read TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Charles Dickens

- Performer: -

Read book online «Tales from Dickens by Charles Dickens (books you need to read TXT) 📕». Author - Charles Dickens

THE CHILD OF THE MARSHALSEA

On the first night of his return to the house of his childhood Arthur had noticed there a little seamstress, with pale, transparent face, hazel eyes and a figure as small as a child's. She wore a spare thin dress, spoke little, and passed through the rooms noiselessly and shy. They called her "Little Dorrit." She came in the morning and sewed quietly till nightfall, when she vanished. It had been so rare in the old days for any one to please the mistress of that gloomy house that the little creature's presence there interested Arthur greatly and he longed to know something of her history.

He soon found there was nothing to be learned from Flintwinch, and so one night he followed Little Dorrit when she left the house. To his great surprise he saw her finally enter a great bare building surrounded with spiked walls and called The Marshalsea.

This was a famous prison where debtors were kept. In those days the law not only permitted a man to be put in jail for debt, but compelled him to stay there till all he owed was paid—a strange custom, since while he was in jail he was unable to earn any money to pay with. In fact, in many cases poor debtors had to stay there all their lives.

Inside the walls of the Marshalsea the wives and children of unfortunate prisoners were allowed to come to live with them just as in a boarding-house or hotel, but the debtors themselves could never pass out of the gate. Arthur entered the prison ignorant of its rules and so stayed too long, for presently the bell for closing rang, the gates were shut, and he had to stay inside all night. This was not so pleasant, but it gave him a chance easily to find out all he wished to learn of Little Dorrit's history.

Her father, before she was born, had lost all his money through a business failure, and had thus been thrown into the Marshalsea. There Amy, or Little Dorrit, as they came to call her, was born; there her mother had languished away, and there she herself had always lived, mothering her pretty frivolous sister Fanny, and her lazy, ne'er-do-well brother, "Tip."

Her father had been an inmate of the prison so many years that he was called "The Father of the Marshalsea." From being a haughty man of wealth, he had become a shabby old white-haired dignitary with a soft manner, who took little gifts of money which any one gave him half-shame-facedly and to the mortification of Little Dorrit alone.

The child had grown up the favorite of the turnkeys and of all the prison, calling the high, blank walls "home." When she was a little slip of a girl she had her sister and brother sent to night-school for a time, and later taught herself fine sewing, so that at the time Arthur Clennam returned to London she was working every day outside the walls, for small wages. Each night she returned to the prison to prepare her father's supper, bringing him whatever she could hide from her own dinner at the house where she sewed, loving him devotedly through all.

She even had a would-be lover, too. The son of one of the turnkeys, a young man with weak legs and weak, light hair, soft-hearted and soft-headed, had long pursued her in vain. He was now engaged in seeking comfort for his hopeless love by composing epitaphs for his own tombstone, such as:

Here Lie the Mortal Remains of

JOHN CHIVERY

Never Anything Worth Mentioning

Who Died of a Broken Heart, Requesting With

His Last Breath that the Word

AMY

Might be Inscribed Over His Ashes

Which Was Done by His Afflicted Parents

Old Mr. Dorrit held his position among the Marshalsea prisoners with great fancied dignity and received all visitors and new-comers in his room like a man of society at home. During that evening Arthur called on him and treated the old man so courteously and talked to Little Dorrit with such kindness that she began to love him from that moment.

Many things of Little Dorrit's pathetic story Arthur learned that night. His first surprise at finding her in the Clennam house mingled strangely with his old thought that his father on his death-bed seemed to be troubled by some remorseful memory; and as he slept in the gloomy prison he dreamed that the little seamstress was in some mysterious way mingled with this wrong and remorse.

There was more truth than fancy in this dream. Not knowing the true history of his parentage, and wholly ignorant of the sad life and death of the poor singer, his own unhappy mother, Arthur had never heard the name Dorrit. He did not know, to be sure, that it was the name of the wealthy patron who had once educated her. As a matter of fact, this patron had been Little Dorrit's own uncle, who now was living in poverty. It was to his youngest niece that the will Mrs. Clennam had wickedly hidden declared the money should go. And as Little Dorrit was this niece, it rightfully belonged to her. The real reason of Mrs. Clennam's apparent kindness to Little Dorrit was the pricking of her conscience, which gave her no rest.

But all this Arthur could not guess. Nevertheless, he had gained such an interest in the little seamstress that next day he determined to find out all he could about her father's unfortunate affairs.

He had great difficulty in this. The Government had taken charge of old Mr. Dorrit's debts, and his affairs were in the hands of a department which some people sneeringly called the "Circumlocution Office"—because it took so much time and talk for it to accomplish anything. This department had a great many clerks, every one of whom seemed to have nothing to do but to keep people from troubling them by finding out anything.

Arthur went to one clerk, who sent him to a Mr. Tite Barnacle, a fat, pompous man with a big collar, a big watch chain and stiff boots. Mr. Barnacle treated him quite as an outsider and would give him no information whatever. Then he tried another department, where they said they knew nothing of the matter. Still a third advised him not to bother about it. So at last he had to give up, quite discouraged.

Though he could do nothing for Little Dorrit's father, Arthur did what he could for her lazy brother. He paid his debts so that he was released from the Marshalsea, and this kindness, though Tip himself was ungrateful to the last degree, endeared him still more to Little Dorrit, who needed his friendship so greatly.

The night her brother was released she came to Arthur to thank him—alone save for a half-witted woman named Maggie, who believed she herself was only ten years old, and called Little Dorrit "Little Mother," and who used to go with her when she went through the streets at night. Little Dorrit was dressed so thinly and looked so slight and helpless that when she left, Arthur felt as if he would like to take her up in his arms and carry her home again.

It would have been better if he had. For when they got back to the Marshalsea the prison gates had closed for the night and they had to stay out till morning. They wandered in the cold street till nearly dawn; then a kind-hearted sexton who was opening a church let them come in and made Little Dorrit a bed of pew cushions, and there she slept a while with a big church-book for a pillow. Arthur did not know of this adventure till long afterward, for Little Dorrit would not tell him for fear he should blame himself for letting them go home alone.

Little Dorrit had one other valuable friend beside Arthur at this time. This was a rent collector named Pancks, who was really kind-hearted, but who was compelled to squeeze rent money out of the poor by his master. The latter looked so good and benevolent that people called him "The Patriarch," but he was at heart a genuine skinflint, for whose meanness Pancks got all the credit. Pancks was a short, wiry man, with a scrubby chin and jet-black eyes, and when he walked or talked he puffed and blew and snorted like a little steam-engine.

Little Dorrit used sometimes to go to sew at the house of "The Patriarch," and Pancks often saw her there. One day he greatly surprised her by asking to see the palm of her hand, and then he pretended to read her fortune. He told her all about herself (which astonished her, for she did not know that he knew anything of her history), and then, with many mysterious puffs and winks, he told her she would finally be happy. After that she seemed to meet Pancks wherever she went—at Mrs. Clennam's and at the Marshalsea as well—but at such meetings he would pretend not to know her. Only sometimes, when no one else was near, he would whisper:

See page 269

"I'm Pancks, the gipsy—fortune-telling."

These strange actions puzzled Little Dorrit very much. But she was far from guessing the truth: that Pancks had for some time been interested (as had Arthur Clennam) in finding out how her father's affairs stood. He had discovered thus, accidentally, that old Mr. Dorrit was probably the heir at law to a great estate that had lain for years forgotten, unclaimed and growing larger all the time. The question now was to prove this, and this, Pancks, out of friendship for Little Dorrit, was busily trying to do.

One day the rent-collector came to Arthur to tell him that he had succeeded. The proof was all found. Mr. Dorrit's right was clear; all he had to do was to sign his name to a paper, and the Marshalsea gates would open and he would be free and a rich man.

Arthur found Little Dorrit and told her the glad tidings. They made her almost faint for joy, although all her rejoicing was for her father. Then he put her in a carriage and drove as fast as possible with her to the prison to carry her father the great news.

Little Dorrit told the old man with her arms around his neck, and as she clasped him, thinking that she had never yet in her life known him as he had once been, before his prison years, she cried:

"I shall see him as I never saw him yet—my dear love, with the dark cloud cleared away! I shall see him, as my poor mother saw him long ago! O my dear, my dear! O father, father! O thank God, thank God!"

So "The Father of the Marshalsea" left the old prison, in which he had lived so long, and all the prisoners held a mass-meeting and gave him a farewell address and a dinner.

On the last day, when they drove away from the iron gates, old Mr. Dorrit was in fine, new clothing, and Tip and Fanny were clad in the height of fashion. Poor Little Dorrit, in joy for her father and grief at parting from Arthur (for they were to go abroad at once), did not appear at the last moment, and Arthur, who had come to see them off, hastening to her room, found that she had fainted away. He carried her gently down to the carriage, and as he lifted her in, he saw she had put on the same thin little dress that she had worn

Comments (0)