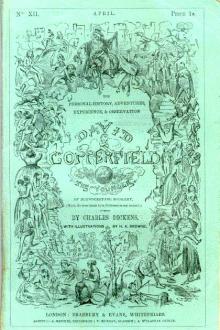

Tales from Dickens by Charles Dickens (books you need to read TXT) 📕

People have often wondered how Dickens found time to accomplish so many different things. One of the secrets of this, no doubt, was his love of order. He was the most systematic of men. Everything he did "went like clockwork," and he prided himself on his punctuality. He could not work in a room unless everything in it was in its proper place. As a consequence of this habit of regularity, he never wasted time.

The work of editorship was very pleasant to Dickens, and scarcely three years after his leaving the Daily News he began the publication of a new magazine which he called Household Words. His aim was to make it cheerful, useful and at the same time cheap, so that the poor could afford to buy it as well as the rich. His own sto

Read free book «Tales from Dickens by Charles Dickens (books you need to read TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Charles Dickens

- Performer: -

Read book online «Tales from Dickens by Charles Dickens (books you need to read TXT) 📕». Author - Charles Dickens

Wherever he looked he seemed to see her, and just as she herself in a foreign country found herself looking and listening for his step and voice, so, too, it was with him.

In the days that followed he thought of her all the while. He was too depressed and too retiring and unhappy to mingle with the other prisoners, so he kept his own room and made no friends. The rest disliked him and said he was proud or sullen.

A burning, reckless mood soon added its sufferings to his dread and hatred of the place. The thought grew on him that he would in the end break his heart and die there. He felt that he was being stifled, and at times the longing to be free made him believe he must go mad. A week of this suffering found him in his bed in the grasp of a slow, wasting fever. He felt light-headed and delirious, and heard tunes playing that he knew were only in his brain.

One day when he had dragged himself to his chair by the window, the door of his room seemed to open to a quiet figure, which dropped a mantle it wore; then it seemed to be Little Dorrit in her old dress, and it seemed first to smile and then to burst into tears.

He roused himself, and all at once he saw that it was no dream. She was really there, kneeling by him now with her tears falling on his hands and her voice crying, "Oh, my best friend! Don't let me see you weep! I am your own poor child come back!"

No one had told her he was ill, for she had just returned from Italy. She made the room fresh and neat, sewed a white curtain for its window, and sent out for grapes, roast chicken and jellies, and every good thing. She sat by him all day, smoothing his hot pillow or giving him a cooling drink.

Though he had been strangely blind, he knew at last that she must have loved him all along. And to find her great heart turned to him thus in his misfortune made him realize that during all those months in the lonely prison he had been loving her, too, though he had not known it.

A feeling of peace came to him. Whenever he opened his eyes he saw her at his side—the same trusting Little Dorrit that he had always known.

V"ALL'S WELL THAT ENDS WELL"

All the while these things were happening, Mrs. Clennam and Flintwinch had continued their grim partnership.

Mrs. Clennam at last decided to burn the part of the will she had hidden, so that her share in the wicked plan could never be found out. Flintwinch, however, wishing for his own purposes to keep her in his power, deceived her. He cunningly put in its place a worthless piece of paper, and this Mrs. Clennam burned instead. Flintwinch then locked up the real piece in an iron box, with a lot of private letters that had been written by the poor crazed singer to Mrs. Clennam, begging her forgiveness. The box he gave to his brother, who took it to Holland with him for safe-keeping.

But Flintwinch, in this deception, overreached himself.

There was an adventurer in Holland named Rigaud, who used to drink and smoke with this brother. He was an oily villain, who had been in jail in France on suspicion of having murdered his wife. He had shaggy dry hair streaked with red, and a thick mustache, and when he smiled his eyes went close together, his mustache went up under his hooked nose, and his nose came down over his mustache. Rigaud saw the box, concluded it contained something valuable, and made up his mind to get it. His chance came when the brother of Flintwinch died suddenly one day, and he lost no time in making away with the iron box.

By means of the letters it contained, he soon guessed the secret which Mrs. Clennam had been for so many years at such pains to conceal, and, deciding that by this knowledge he could squeeze money out of her, he came to London to find and threaten her.

But she, believing she had burned the part of the will which Rigaud claimed to possess, refused to listen to him, until at last, maddened by her refusals, he searched out the Dorrits.

He soon discovered that the man who had educated the singer (Arthur's real mother) was Frederick Dorrit, Little Dorrit's dead uncle, and that it was Little Dorrit herself, since she was his youngest niece, from whom the money was now being unjustly kept.

Rigaud easily found Little Dorrit, for she was now in the Marshalsea nursing Arthur, where he lay sick, and to her the cunning adventurer sent a copy of the paper in a sealed packet, asking her, if it was not reclaimed before the prison closed that same night, to open and read it herself.

He then went to the Clennam house, told Mrs. Clennam and Flintwinch what he had done and demanded money at once as the price of his reclaiming the packet before Little Dorrit should learn the secret it held.

At this Flintwinch had to confess what he had done, and Mrs. Clennam knew that the fatal paper had not been burned, after all.

The wretched woman, seeing this sharp end to all her scheming, was almost distracted. She had not walked a step for twelve years, but now her excitement and frenzy gave her unnatural strength. She rose from her invalid chair and ran with all her speed from the house. Old Affery, the servant, followed her mistress, wringing her hands as she tried vainly to overtake her.

Mrs. Clennam did not pause till she had reached the prison and found Little Dorrit. She told her to open the packet at once and to read what it contained, and then, kneeling at her feet, she promised to restore to her all she had withheld, and begged her to forgive and to come back with her to tell Rigaud that she already knew the secret and that he might do his worst.

Little Dorrit was greatly moved to see the stern, gray-haired woman at her feet. She raised and comforted her, assuring her that, come what would, Arthur should never learn the truth from her lips. This return of good for evil from the one she had most injured brought the tears to the hard woman's eyes. "God bless you," she said in a broken voice.

Side by side they hastened back to the Clennam house, but as they reached the entrance of its dark courtyard there came a sudden noise like thunder. For one instant they saw the building, with the insolent Rigaud waiting smoking in the window; then the walls heaved, surged outward, opened and fell into pieces. Its great pile of chimneys rocked, broke and tumbled on the fragments, and only a huge mass of timbers and stone, with a cloud of dust hovering over it, marked the spot where it had stood.

The rotten old building, propped up so long, had fallen at last. For years old Affery had insisted that the house was haunted. She had often heard mysterious rustlings and noises, and in the mornings sometimes she would find little heaps of dust on the floors. Curious, crooked cracks would appear, too, in the walls, and the doors would stick with no apparent reason. These things, of course, had been caused by the gradual settling of the crazy walls and timbers, which now finally had collapsed all at once.

Frightened, they ran back to the street and there Mrs. Clennam's strange strength left her, and she fell in a heap upon the pavement.

She never from that hour was able to speak a word or move a finger. She lived for three years in a wheel-chair, but she lived—and died—like a statue.

For two days workmen dug industriously in the ruins before they found the body of Rigaud, with his head smashed to atoms beneath a huge beam.

They dug longer than that for the body of Flintwinch, and stopped at last when they came to the conclusion that he was not there. By that time, however, he had had a chance to get together all of the firm's money he could lay his hands on and to decamp. He was never seen again in England, but travelers claimed to have seen him in Holland, where he lived comfortably under the name of "Mynheer Von Flyntevynge"—which is, after all, about as near as one can come to saying "Flintwinch" in Dutch.

No one grieved greatly over his loss. It was long before Arthur knew of these events, and Little Dorrit was too happy in nursing him back to health to think much about it.

She was not content with this, either, but wrote to Mr. and Mrs. Meagles, who were abroad, of the sick man's misfortune. The former went at once in search of Doyce and brought him back to London, where together they set the firm of "Doyce and Clennam" on its feet again and arranged to buy Arthur's liberty. They did not tell Arthur anything of this, however, in order that they might surprise him.

Mr. Meagles, for Little Dorrit's sake, tried hard to find the fragment of the will which Rigaud had kept in the iron box. But it was Tattycoram, the little maid with the bad temper, who finally found it in a lodging Rigaud had occupied, and brought it to Mr. Meagles, praying on her knees that he take her back into his service, which, to be sure, he was very glad to do.

Arthur, while he was slowly growing better, had thought much of his condition. Though Little Dorrit had begged him again and again to take her money and use it as his own, he had refused, telling her as gently as he could that now that she was rich and he a ruined man, this could never be, and that, as the time had long gone by when she and the Marshalsea had anything in common, they two must soon part.

One day, however, when he was well enough to sit up, Little Dorrit came to his room in the prison and told him she had received a very great fortune and asked him again if he would not take it.

"Never," he told her.

"You will not take even half of it?" she asked pleadingly.

"Never, dear Little Dorrit!" he said emphatically.

Then, at last, she laid her face on his breast crying:

"I have nothing in the world. I am as poor as when I lived here in the Marshalsea. I have just found that papa gave all we had to Mr. Merdle and it is swept away with the rest. My great fortune now is poverty, because it is all you will take. Oh, my dearest and best, are you quite sure you will not share my fortune with me now?"

He had locked her in his arms, and his tears were falling on her cheek as she said joyfully:

"I never was rich before, or proud, or happy. I would rather pass my life here in prison with you, and work daily for my bread, than to have the greatest fortune that ever was told and be the greatest lady that ever was honored!"

But Arthur's prison life was to be short. For Mr. Meagles and Doyce burst upon them with all the other good news at

Comments (0)