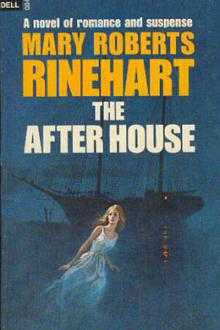

The After House by Mary Roberts Rinehart (dark books to read TXT) 📕

McWhirter it was who got me my berth on the Ella. It must have been about the 20th of July, for the Ella sailed on the 28th. I was strong enough to leave the hospital, but not yet physically able for any prolonged exertion. McWhirter, who was short and stout, had been alternately flirting with the nurse, as she moved in and out preparing my room for the night, and sizing me up through narrowed eyes.

"No," he said, evidently following a private line of thought; "you don't belong behind a counter, Leslie. I'm darned if I think you belong in the medical profession, either. The British army'd suit you."

"The - what?"

"You know - Kipling ide

Read free book «The After House by Mary Roberts Rinehart (dark books to read TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Mary Roberts Rinehart

- Performer: -

Read book online «The After House by Mary Roberts Rinehart (dark books to read TXT) 📕». Author - Mary Roberts Rinehart

“Where’s Williams?” He turned to me.

“I can get him for you.”

“Tell him to bring me a highball. My mouth’s sticky.” He ran his tongue over his dry lips. “And - take a message from me to Richardson -” He stopped, startled. Indeed, Miss Lee and I had both started. “To who’s running the boat, anyhow? Singleton?”

“Mr. Singleton is a prisoner in the forward house,” I said gravely.

The effect of this was astonishing. He stared at us both, and, finding corroboration in Miss Lee’s face, his own took on an instant expression of relief. He dropped to the side of the bed, and his color came slowly back. He even smiled - a crafty grin that was inexpressibly horrible.

“Singleton!” he said. “Why do they - how do they know it was he?”

“He had quarreled with the captain last night, and he was on duty at the time of the when the thing happened. The man at the wheel claims to have seen him in the chartroom just before, and there was other evidence, I believe. The lookout saw him forward, with something - possibly the axe. Not decisive, of course, but enough to justify putting him in irons. Somebody did it, and the murderer is on board, Mr. Turner.”

His grin had faded, but the crafty look in his pale-blue eyes remained.

“The chartroom was dark. How could the steersman -” He checked himself abruptly, and looked at us both quickly. “Where are - they?” he asked in a different tone.

“On deck.”

“We can’t keep them in this weather.”

“We must,” I said. “We will have to get to the nearest port as quickly as we can, and surrender ourselves and the bodies. This thing will have to be sifted to the bottom, Mr. Turner. The innocent must not suffer for the guilty, and every one on the ship is under suspicion.”

He fell into a passion at that, insisting that the bodies be buried at once, asserting his ownership of the vessel as his authority, demanding to know what I, a forecastle hand, had to say about it, flinging up and down the small room, showering me with invective and threats, and shoving Miss Lee aside when she laid a calming hand on his arm. The cut on his chin was bleeding again, adding to his wild and sinister expression. He ended by demanding Williams.

I opened the door and called to Charlie Jones to send the butler, and stood by, waiting for the fresh explosion that was coming. Williams shakily confessed that there was no whiskey on board.

“Where is it?” Turner thundered.

Williams looked at me. He was in a state of inarticulate fright.

“I ordered it overboard,” I said.

Turner whirled on me, incredulity and rage in his face.

“You!”

I put the best face I could on the matter, and eyed him steadily. “There has been too much drinking on this ship,” I said. “If you doubt it, go up and look at the three bodies on the deck.”

“What have you to do about it?” His eyes were narrowed; there was menace in every line of his face.

“With Schwartz gone, Captain Richardson dead, and Singleton in irons, the crew had no officers. They asked me to take charge.”

“So! And you used your authority to meddle with what does not concern you The ship has an officer while I am on it. And there will be no mutiny.”

He flung into the main cabin, and made for the forward companionway. I stepped back to allow Miss Lee to precede me. She was standing, her back to the dressing-stand, facing the door. She looked at me and made a helpless gesture with her hands, as if the situation were beyond her. Then I saw her look down. She took a quick step or two toward the door, and, stooping picked up some small object from almost under my foot. The incident would have passed without notice, had she not, in attempting to wrap it in her handkerchief, dropped it. I saw then that it was a key.

“Let me get it for you” I said. To my amazement, she put her foot over it.

“please see what Mr: Turner is doing,” she said. “It is the key to my jewel-case.”

“Will you let me see it?”

“No.”

“It is not the key to a jewel-case.”

“It does not concern you what it is.”

“It is the key to the storeroom door”

“You are stronger than I am. You look the brute. You can knock me away and get it.”

I knew then, of course, that it was the storeroom key. But I could not take it by force. And so defiantly she faced me, so valiant was every line of her slight figure, that I was ashamed of my impulse to push her aside and take it. I loved her with every inch of my overgrown body, and I did the thing she knew I would do. I bowed and left the cabin. But I had no intention of losing the key. I could not take it by force, but she knew as well as I did what finding it there in Turner’s room meant. Turner had locked me in. But I must be able to prove it - my wits against hers, and the advantage mine. I had the women under guard.

I went up on deck.

A curious spectacle revealed itself. Turner, purple with anger, was haranguing the men, who stood amidships, huddled together, but grim and determined withal. Burns, a little apart from the rest, was standing, sullen, his arms folded. As Turner ceased, he took a step forward.

“You are right, Mr. Turner,” he said. “It’s your ship, and it’s up to you to say where she goes and how she goes, sir. But some one will hang for this, Mr. Turner, - some one that’s on this deck now; and the bodies are going back with us - likewise the axe. There ain’t going to be a mistake - the right man is going to swing.”

“That’s mutiny!”

“Yes, sir,” Burns acknowledged, his face paling a little. “I guess you could call it that.”

Turner swung on his heel and went below, where Jones, relieved of guard duty by Burns, reported him locked in his room, refusing admission to his wife and Miss Lee, both of whom had knocked on the door.

The trouble with Turner added to the general misery of the situation. Burns got our position at noon with more or less exactness, and the general working of the Ella went on well enough. But the situation was indescribable. Men started if a penknife dropped, and swore if a sail flapped. The call of the boatswain’s pipe rasped their ears, and the preparation for stowing the bodies in the jollyboat left them unnerved and sick. Some sort of a meal was cooked, but no one could eat; Williams brought up, untasted, the luncheon he had carried down to the after house.

At two o’clock all hands gathered amidships, and the bodies were carried forward to where the boat, lowered in its davits and braced, lay on the deck. It had been lined with canvas and tarpaulin, and a cover of similar material lay ready to be nailed in place. All the men were bareheaded. Many were in tears. Miss Lee came forward with us, and it was from her prayer-book that I, too moved for self-consciousness, read the burial-service.

“I am the resurrection and the life,” I read huskily.

The figures at my feet, in their canvas shrouds, rolled gently with the rocking of the ship; the sun beat down on the decks, on the bare heads of the men, on the gilt edges of the prayer-book, gleaming in the light, on the last of the land-birds, drooping in the heat on the main cross.-trees.

“… For man walketh in a vain shadow,” I read, “and disquieteth himself in vain … .

“O spare me a little, that I may recover my strength: before I go hence, and be no more seen.”

Mrs. Johns and the stewardess came up late in the afternoon. We had railed off a part of the deck around the forward companionway for them, and none of the crew except the man on guard was allowed inside the ropes. After a consultation, finding the ship very short-handed, and unwilling with the night coming on to trust any of the men, Burns and I decided to take over this duty ourselves, and; by stationing ourselves at the top of the companionway, to combine the duties of officer on watch and guard of the after house. To make the women doubly secure, we had Oleson nail all the windows closed, although they were merely portholes. Jones was no longer on guard below, and I had exchanged Singleton’s worthless revolver for my own serviceable one.

Mrs. Johns, carefully dressed, surveyed the railed-off deck with raised eyebrows.

“For - us?” she asked, looking at me. The men were gathered about the wheel aft, and were out of earshot. Mrs. Sloane had dropped into a steamer-chair, and was lying back with closed eyes.

“Yes, Mrs. Johns.”

“Where have you put them?”

I pointed to where the jollyboat, on the port side of the ship, swung on its davits.

“And the mate, Mr. Singleton?”

“He is in the forward house.”

“What did you do with the - the weapon?”

“Why do you ask that?”

“Morbid curiosity,” she said, with a lightness of tone that rang false to my ears. “And then - naturally, I should like to be sure that it is safely overboard, so it will not be” - she shivered - ” used again.”

“It is not overboard, Mrs. Johns,” I said gravely. “It is locked in a safe place, where it will remain until the police come to take it.”

“You are rather theatrical, aren’t you?” she scoffed, and turned away. But a second later she came back to me, and put her hand on my arm. “Tell me where it is,” she begged. “You are making a mystery of it, and I detest mysteries.”

I saw under her mask of lightness then: she wanted desperately to know where the axe was. Her eyes fell, under my gaze.

“I am sorry. There is no mystery. It is simply locked away for safe-keeping.”

She bit her lip.

“Do you know what I think?” she said slowly. “I think you have hypnotized the crew, as you did me - at first. Why has no one remembered that you were in the after house last night, that you found poor Wilmer Vail, that you raised the alarm, that you discovered the captain and Karen? Why should I not call the men here and remind them of all that?”

“I do not believe you will. They know I was locked in the storeroom. The door - the lock -”

“You could have locked yourself in.”

“You do not know what you are saying!”

But I had angered her, and she went on cruelly: -

“Who are you, anyhow? You are not a sailor. You came here and were taken on because you told a hard-luck story. How do we know that you came from a hospital? Men just out of prison look as you did. Do you know what we called you, the first two days out? We called you Elsa’s jail-bird And now, because you have dominated the crew, we are in your hands!”

“Do Mrs. Turner and Miss Lee think that?”

“They feel as I do. This is a picked crew men the Turner line has employed for years.”

“You are very brave, Mrs. Johns,” I said. “If I were what you think I am, I would be a dangerous enemy.”

“I am not afraid of you.”

Comments (0)