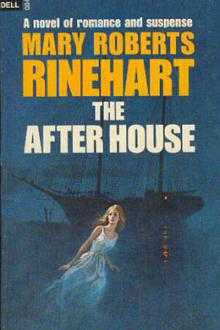

The After House by Mary Roberts Rinehart (dark books to read TXT) 📕

McWhirter it was who got me my berth on the Ella. It must have been about the 20th of July, for the Ella sailed on the 28th. I was strong enough to leave the hospital, but not yet physically able for any prolonged exertion. McWhirter, who was short and stout, had been alternately flirting with the nurse, as she moved in and out preparing my room for the night, and sizing me up through narrowed eyes.

"No," he said, evidently following a private line of thought; "you don't belong behind a counter, Leslie. I'm darned if I think you belong in the medical profession, either. The British army'd suit you."

"The - what?"

"You know - Kipling ide

Read free book «The After House by Mary Roberts Rinehart (dark books to read TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Mary Roberts Rinehart

- Performer: -

Read book online «The After House by Mary Roberts Rinehart (dark books to read TXT) 📕». Author - Mary Roberts Rinehart

“You are leaving me only one thing to do,” I said. “I shall surrender myself to the men at once.” I took out my revolver and held it out to her. “This rope is a deadline. The crew know, and you will have no trouble; but you must stand guard here until some one else is sent.”

She took the revolver without a word, and, somewhat dazed by this new turn of events, I went aft. The men were gathered there, and I surrendered myself. They listened in silence while I told them the situation. Burns, who had been trying to sleep, sat up and stared at me incredulously.

“It will leave you pretty short-handed, boys,” I finished, “but you’d better fasten me up somewhere. But I want to be sure of one thing first: whatever happens, keep the guard for the women.”

“We’d like to talk it over, Leslie,” Burns said, after a word with the others.

I went forward a few feet, taking care to remain where they could see me, and very soon they called me. There had been a dispute, I believe. Adams and McNamara stood off from the others, their faces not unfriendly, but clearly differing from the decision. Charlie Jones, who, by reason of long service and a sort of pious control he had in the forecastle, was generally spokesman for the crew, took a step or two toward me.

“We’ll not do it, boy,” he said. “We think we know a man when we see one, as well as having occasion to know that you’re white all through. And we’re not inclined to set the talk of women against what we think best to do. So you stick to your job, and we’re back of you.”

In spite of myself, I choked up. I tried to tell them what their loyalty meant to me; but I could only hold out my hand, and, one by one, they came up and shook it solemnly.

“We think,” McNamara said, when, last of all, he and Adams came up, “that it would be best, lad, if we put down in the log-book all that has happened last night and to-day, and this just now, too. It’s fresh in our minds now, and it will be something to go by.”

So Burns and I got the log-book from the captain’s cabin. The axe was there, where we had placed it earlier in the day, lying on the white cover of the bed. The room was untouched, as the dead man had left it - a collar on the stand, brushes put down hastily, a half-smoked cigar which had burned a long scar on, the wood before it had gone out. We went out silently, Burns carrying the book, I locking the door behind us.

Mrs. Johns, sitting near the companionway with the revolver on her knee, looked up and eyed me coolly.

“So they would not do it!”

“I am sorry to disappoint you - they would not.”

She held up my revolver to me, and smiled cynically.

“Remember,” she said, “I only said you were a possibility.”

“Thank you; I shall remember.”

By unanimous consent, the task of putting down what had happened was given to me. I have a copy of the log-book before me now, the one that was used at the trial. The men read it through before they signed it.

August thirteenth.

This morning, between two-thirty and three o’clock, three murders were committed on the yacht Ella. At the request of Mrs. Johns, one of the party on board, I had moved to the after house to sleep, putting my blanket and pillow in the storeroom and sleeping on the floor there. Mrs. Johns gave, as her reason, a fear of something going wrong, as there was trouble between Mr. Turner and the captain. I slept with a revolver beside me and with the door of the storeroom open.

At some time shortly before three o’clock I wakened with a feeling of suffocation, and found that the door was closed and locked on the outside. I suspected a joke among the crew, and set to work with my penknife to unscrew the lock. When I had two screws out, a woman screamed, and I broke down the door.

As the main cabin was dark, I saw no one and could not tell where the cry came from. I ran into Mr. Vail’s cabin, next the storeroom, and called him. His door was standing open. I heard him breathing heavily. Then the breathing stopped. I struck a match, and found him dead. His head had been crushed in with an axe, the left hand cut off, and there were gashes on the right shoulder and the abdomen.

I knew the helmsman would be at the wheel, and ran up the after companionway to him and told him. Then I ran forward and called the first mate, Mr. Singleton, who was on duty. He had been drinking. I asked him to call the captain, but he did not. He got his revolver, and we hurried down the forward companion. The body of the captain was lying at the foot of the steps, his head on the lowest stair. He had been killed like Mr. Vail. His cap had been placed over his face.

The mate collapsed on the steps. I found the light switch and turned it on. There was no one in the cabin or in the chartroom. I ran to Mr. Turner’s room, going through Mr. Vail’s and through the bathroom. Mr. Turner was in bed, fully dressed. I could not rouse him. Like the mate, he had been drinking.

The mate had roused the crew, and they gathered in the chartroom. I told them what had happened, and that the murderer must be among us. I suggested that they stay together, and that they submit to being searched for weapons.

They went on deck in a body, and I roused the women and told them. Mrs. Turner asked me to tell the two maids, who slept in a cabin off the chartroom. I found their door unlocked, and, receiving no answer, opened it. Karen Hansen, the lady’s-maid, was on the floor, dead, with her skull crushed in. The stewardess, Henrietta Sloane, was fainting in her bunk. An axe had been hurled through the doorway as the Hansen woman fell, and was found in the stewardess’s bunk.

Dawn coming by that time, I suggested a guard at the two companionways, and this was done. The men were searched and all weapons taken from them. Mr. Singleton was under suspicion, it being known that he had threatened the captain’s life, and Oleson, a lookout, claiming to have seen him forward where the axe was kept.

The crew insisted that Singleton be put in irons. He made no objection, and we locked him in his own room in the forward house. Owing to the loss of Schwartz, the second mate, already recorded in this log-book (see entry for August ninth), the death of the captain, and the imprisonment of the first mate, the ship was left without officers. Until Mr. Turner could make an arrangement, the crew nominated Burns, one of themselves, as mate, and asked me to assume command. I protested that I knew nothing of navigation, but agreed on its being represented that, as I was not one of them, there could be i11 feeling.

The ship was searched, on the possibility of finding a stowaway in the hold. But nothing was found. I divided the men into two watches, Burns taking one and I the other. We nailed up the after companionway, and forbade any member of the crew to enter the after house. The forecastle was also locked, the men bringing their belongings on deck. The stewardess recovered and told her story, which, in her own writing, will be added to this record.

The bodies of the dead were brought on deck and sewed into canvas, and later, with appropriate services, placed in the jollyboat, it being the intention, later on, to tow the boat behind us. Mr. Turner insisted that the bodies be buried at sea, and, on the crew opposing this, retired to his cabin, announcing that he considered the position of the men a mutiny.

Some feeling having arisen among the women of the party that I might know more of the crimes than was generally supposed, having been in the after house at the time they were committed, and having no references, I this afternoon voluntarily surrendered myself to Burns, acting first mate. The men, however, refused to accept this surrender, only two, Adams and McNamara, favoring it. I expect to give myself up to the police at the nearest port, until the matter is thoroughly probed.

The axe is locked in the captain’s cabin.

(Signed) RALPH LESLIE. John Robert Burns Charles Klineordlinger (Jones) William McNamara Witnesses Carl L. Clarke Joseph Q. Adams John Oleson Tom MacKenzie Obadiah Williams

Williams came up on deck late that afternoon, with a scared face, and announced that Mr. Turner had locked himself in his cabin, and was raving in delirium on the other side of the door. I sent Burns down having decided, in view of Mrs. Johns’s accusation, to keep away from the living quarters of the family. Burns’s report corroborated what Williams had said. Turner was in the grip of delirium tremens, and the Ella was without owner or officers.

Turner refused to open either door for us. As well as we could make out, he was moving rapidly but almost noiselessly up and down the room, muttering to himself, now and then throwing himself on the bed, only to get up at once. He rang his bell a dozen times, and summoned Williams, only, in reply to the butler’s palpitating knock, to stand beyond the door and refuse to open it or to voice any request. The situation became so urgent that finally I was forced to go down, with no better success.

Mrs. Turner dragged herself across, on the state of affairs being reported to her, and, after two or three abortive attempts, succeeded in getting a reply from him.

“Marsh!” she called. “I want to talk to you. Let me in.”

“They’ll get us,” he said craftily.

“Us? Who is with you?”

“Vail,” he replied promptly. “He’s here talking. He won’t let me sleep.”

“Tell him to give you the key and you will keep it for him so no one can get him,” I prompted. I had had some experience with such cases in the hospital.

She tried it without any particular hope, but it succeeded immediately. He pushed the key out under the door, and almost at once we heard him throw himself on the bed, as if satisfied that the problem of his security was solved.

Mrs. Turner held the key out to me, but I would not take it.

“Give it to Williams,” I said. “You must understand, Mrs. Turner, that I cannot take it.

She was a woman of few words, and after a glance at my determined face she turned to the butler.

“You will have to look after Mr. Turner, Williams. See that he is comfortable, and try to keep him in bed.”

Williams put out a trembling hand, but, before he took the key, Turner’s voice rose petulantly on the other side of the door.

“For God’s sake, Wilmer,” he cried plaintively, “get out and let me sleep I haven’t slept for a month.”

Williams gave a whoop of fear, and ran out of the cabin, crying that the ship was haunted and that Vail had come back. From that moment, I believe, the after house was the safest spot on the ship. To my knowledge, no member

Comments (0)