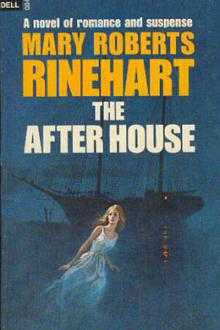

The After House by Mary Roberts Rinehart (dark books to read TXT) 📕

McWhirter it was who got me my berth on the Ella. It must have been about the 20th of July, for the Ella sailed on the 28th. I was strong enough to leave the hospital, but not yet physically able for any prolonged exertion. McWhirter, who was short and stout, had been alternately flirting with the nurse, as she moved in and out preparing my room for the night, and sizing me up through narrowed eyes.

"No," he said, evidently following a private line of thought; "you don't belong behind a counter, Leslie. I'm darned if I think you belong in the medical profession, either. The British army'd suit you."

"The - what?"

"You know - Kipling ide

Read free book «The After House by Mary Roberts Rinehart (dark books to read TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Mary Roberts Rinehart

- Performer: -

Read book online «The After House by Mary Roberts Rinehart (dark books to read TXT) 📕». Author - Mary Roberts Rinehart

Oleson and Adams made no attempt to work that day; indeed, Oleson was not able. As I had promised, the breakfast for the after house was placed on the companion steps by Tom, the cook, whence it was removed by Mrs. Sloane. I saw nothing of either Elsa Lee or Mrs. Johns. Burns was inclined to resent the deadline the women had drawn below, and suggested that, since they were so anxious to take care of themselves, we give up guarding the after house and let them do it. We were short-handed enough, he urged, and, if they were going to take that attitude, let them manage. I did not argue, but my eyes traveled over the rail to where the jollyboat rose to meet the fresh sea of the morning, and he colored. After that he made no comment.

Singleton awakened before noon, and ate his first meal since the murders. He looked better, and we had a long talk, I outside the window and he within. He held to his story of the night before, but was still vague as to just how the thing looked. Of what it was he seemed to have no doubt. It was the specter of either the captain or Vail; he excluded the woman, because she was shorter. As I stood outside, he measured on me the approximate height of the apparition - somewhere about five feet eight. He could see Burns’s shirt, he admitted, but the thing had been close to the window.

I found myself convinced against my will, and that afternoon, alone, I made a second and more thorough examination of the forecastle and the hold. In the former I found nothing. Having been closed for over twenty-four hours, it was stifling and full of odors. The crew, abandoning it in haste, had left it in disorder. I made a systematic search, beginning forward and working back. I prodded in and under bunks, and moved the clothing that hung on every hook and swung, to the undoing of my nerves, with every swell. Much curious salvage I found under mattresses and beneath bunks: a rosary and a dozen filthy pictures under the same pillow; more than one bottle of whiskey; and even, where it had been dropped in the haste of flight, a bottle of cocaine. The bottle set me to thinking: had we a “coke” fiend on board, and, if we had, who was it?

The examination of the hold led to one curious and not easily explained discovery. The Ella was in gravel ballast, and my search there was difficult and nerve-racking. The creaking of the girders and floor-plates, the groaning overhead of the trestle-trees, and once an unexpected list that sent me careening, head first, against a ballast-tank, made my position distinctly disagreeable. And above all the incidental noises of a ship’s hold was one that I could not place - a regular knocking, which kept time with the list of the boat.

I located it at last, approximately, at one of the ballast ports, but there was nothing to be seen. The port had been carefully barred and calked over. The sound was not loud. Down there among the other noises, I seemed to feel as well as hear it. I sent Burns down, and he came up, puzzled.

“It’s outside,” he said. “Something cracking against her ribs.”

“You didn’t notice it yesterday, did you?”

“No; but yesterday we were not listening for noises.”

The knocking was on the port side. We went forward together, and, leaning well out, looked over the rail.

The missing marlinespike was swinging there, banging against the hull with every roll of the ship. It was fastened by a rope lanyard to a large bolt below the rail, and fastened with what Burns called a Blackwall hitch - a sailor’s knot.

I find, from my journal, that the next seven days passed without marked incident. Several times during that period we sighted vessels, ail outward bound, and once we were within communicating distance of a steam cargo boat on her way to Venezuela. She lay to and sent her first mate over to see what could be done.

He was a slim little man with dark eyes and a small mustache above a cheerful mouth. He listened in silence to my story, and shuddered when I showed him the jollyboat. But we were only a few days out by that time, and, after all, what could they do? He offered to spare us a hand, if it could be arranged; but, Adams having recovered by that time, we decided to get along as we were. A strange sight we must have presented to the tidy little officer in his uniform and black tie: a haggard, unshaven lot of men, none too clean, all suffering from strain and lack of sleep, with nerves ready to snap; a white yacht, motionless, her sails drooping, - for not a breath of air moved, - with unpolished brasses and dirty decks; in charge of all, a tall youth, unshaven like the rest, and gaunt from sickness, who hardly knew a nautical phrase, who shook the little officer’s hand with a ferocity of welcome that made him change color, and whose uniform consisted of a pair of dirty khaki trousers and a khaki shirt, open at the neck; and behind us, wallowing in the trough of the sea as the Ella lay to, the jollyboat, so miscalled, with its sinister cargo.

The Buenos Aires went on, leaving us a bit cheered, perhaps, but none the better off, except that she verified our bearings. The after house had taken no notice of the incident. None of the women had appeared, nor did they make any inquiry of the cook when he carried down their dinner that night.. As entirely as possible, during the week that had passed, they had kept to themselves. Turner was better, I imagined; but, the few times when Elsa Lee appeared at the companion for a breath of air, I was off duty and missed her. I thought it was by design, and I was desperate for a sight of her.

Mrs. Johns came on deck once or twice while I was there, but she chose to ignore me. The stewardess, however, was not so partisan, and, the day before we met the Buenos Aires, she spent a little time on deck, leaning against the rail and watching me with alert black eyes.

“What are you going to do when you get to land, Mr. Captain Leslie?” she asked. “Are you going to put us all in prison?”

“That’s as may be,” I evaded. She was a pretty little woman, plump and dark, and she slid her hand along the rail until it touched mine. Whereon, I did the thing she was expecting, and put my fingers over hers. She flushed a little, and dimpled.

“You are human, aren’t you?” she asked archly. “I am not afraid of you.”

“No one is, I am sure.”

“Silly! Why, they are all afraid of you, down there.” She jerked her head toward the after house. “They want to offer you something, but none of them will do it.”

“Offer me something?”

She came a little closer, so that her round shoulder touched mine.

“Why not? You need money, I take it. And that’s the one thing they have - money.”

I began to understand her.

“I see,” I said slowly. “They want to bribe me.

She shrugged her shoulders.

“That is a nasty word. They might wish to buy - a key or two that you carry.”

“The storeroom key, of course. But what other?”

She looked around - we were alone. A light breeze filled the sails and flicked the end of a scarf she wore against my face.

“The key to the captain’s cabin,” she said, very low.

That was what they wished to buy: the incriminating key to the storeroom, found on Turner’s floor, and access to the axe, with its telltale prints on the handle.

The stewardess saw my face harden, and put her hand on my arm.

“Now I am afraid of you!” she cried: “When you look like that!”

“.Mrs. Sloane,” I said, “I do not know that you were asked to do this - I think not. But if you were, say for me what I am willing to say for myself: I shall tell what I know, and there is not money enough in the world to prevent my telling it straight. The right man is going to be punished, and the key to the storeroom will be given to the police, and to no one else.”

“But - the other key?”

“That is not in my keeping.”

“I do not believe you!”

“I am sorry,” I said shortly. “As a matter of fact, Burns has that.”

By the look of triumph in her eyes I knew I had told her what she wanted to know. She went below soon after, and I warned Burns that he would probably be approached in the same way.

“Not that I am afraid,” I added. “But keep the little Sloane woman at a distance. She’s quite capable of mesmerizing you with her eyes and robbing you with her hands at the same time.”

“I’d rather you’d carry it,” he said, “although I’m not afraid of the lady. It’s not likely, after

He did not finish, but he glanced aft toward the jollyboat. Poor Burns! I believe he had really cared for the Danish girl. Perhaps I was foolish, but I refused to take the key from him; I felt sure he could be trusted.

The murders had been committed on the early morning of Wednesday, the 12th It was on the following Tuesday that Mrs. Sloane and I had our little conversation on deck, and on Wednesday we came up with the Buenos Aires.

It was on Friday, therefore, two days after the cargo steamer had slid over the edge of the ocean, and left us, motionless, a painted ship upon a painted sea, that the incident happened that completed the demoralization of :he crew.

For almost a week the lookouts had reported ‘All’s well” in response to the striking of the ship’s bell. The hysteria, as Burns and I dubbed it, of the white figure had died away as the men’s nerves grew less irritated. Although we had found no absolute explanation of the marlinespike, an obvious one suggested itself. The men, although giving up their weapons without protest, had grumbled somewhat over being left without means of defense. It was entirely possible, we agreed, that the marlinespike had been so disposed, as some seaman’s resort in time of need.

The cook, taking down the dinner on Friday evening, reported Mr. Turner up and about and partly dressed. The heat was frightful. All day we had had a following breeze, and it had been necessary to lengthen the towing-rope, dropping the jollyboat well behind us. The men, saying little or nothing, dozed under their canvas; the helmsman drooped at the wheel. Under our feet the boards sent up simmering heat waves, and the brasses were too hot to touch.

At four o’clock Elsa Lee came on deck, and spoke to me for the first time in several days. She started when she saw me, and no wonder. In the frenzied caution of the day after the crimes, I

Comments (0)