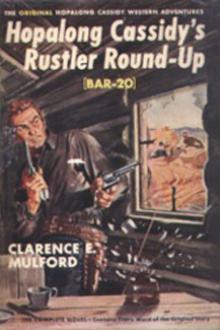

''Bring Me His Ears'' by Clarence E. Mulford (howl and other poems TXT) 📕

"I know how you feel, Mr. Boyd. Have you seen your father since you landed?"

Tom reluctantly shook his head. "It would only reopen the old bitterness and lead to further estrangement. No man shall ever speak to me again as he did--not even him. If you should see him, Jarvis, tell him I asked you to assure him of my affection."

"I shall be glad to do that," replied the clerk. "You missed him by only two days. He asked for you and wished you success, and said your home was open to you when you returned to resume your studies. I think, in his heart, he is proud of you, but too stubborn to admit it." As he spoke he chanced to glance through the window of the store. "Don't look around," he warned. "I want to tell you t

Read free book «''Bring Me His Ears'' by Clarence E. Mulford (howl and other poems TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Clarence E. Mulford

- Performer: -

Read book online «''Bring Me His Ears'' by Clarence E. Mulford (howl and other poems TXT) 📕». Author - Clarence E. Mulford

Songs, jokes, exultant shouts ran along the trains as the valley was left behind, for now the caravan truly was embarked on the journey, and every mile covered put civilization that much farther in the rear. Straight ahead lay the trail, beaten into a plain, broad track leading toward the sunset, a mark which could not be mistaken and which rendered the many compasses valueless so far as the trail itself was concerned.

The first day's travel was a comparatively short one, and during the drive the officers rode back along the lines and again explained the formation which would be used at the next stopping place. This point was so near that the caravan kept on past the noon hour and did not stop until it reached Diamond Spring, a large, crystal spring emptying into a small brook close to a very good camping ground. The former camp no sooner had been left than the tenderfeet began to show their predilection to do as they pleased and to ride madly over the prairie in search of game which was not there, finally gravitating to a common body a mile or more ahead of the wagons, a place to which they stuck with a determination worthy of better things.

At Diamond Spring came the first clash against authority, for the captain had told each lieutenant to get his division across all streams before stopping. The word had been passed along the twin lines and seemed to have been tacitly accepted, yet when the wagons reached the brook many of the last two divisions, thinking the farther bank too crowded and ignoring the formation of the night encampment, pulled up and stopped on the near side. After some argument most of them crossed over and took up their proper places in the corral, but there were some who expressed themselves as being entirely satisfied to remain where they were, since there was no danger from Indians at this point. The animals were turned loose to graze, restrained only by hobbles until nightfall, the oxen in most cases yoked together to save trouble with the stubborn beasts until they should become trained and more docile. They were the most senseless of the draft animals, often stampeding for no apparent cause; the sudden rattle of a chain or a yoke often being all that was needed to turn them into a fleshy avalanche; and while the Indians did not want oxen, they seemed to be aware of the excitable natures of the beasts and made use of their knowledge to start stampedes among the other animals with them, much the same as fulminate of mercury is used to detonate a charge of a more stable explosive.

The first two watches of the night were pleasant, but when Tom Boyd's squad went on duty an hour before midnight there was a change in the weather, and before half an hour had passed the rain fell in sheets and sent some of the guards to seek shelter in the wagons. Two of them were tenderfeet, one of Schoolcraft's friends and a trader. Tom was the so-called corporal of this watch and he was standing his trick as vigilantly as if they were in the heart of the Kiowa or Comanche country. He carefully had instructed his men and had posted them in the best places, and he knew where each of them should be found. After half an hour of the downpour he made the rounds, called the roll and then slipped back into the encampment in search of the missing men. Not knowing them well enough at this time he did not know the wagons to which they belonged, and he had to wait until later to hunt them out.

Dawn found a wet and dispirited camp as the last guard returned to the wagons an hour before they should have left their posts. Not a fire would burn properly and not a breakfast was thoroughly cooked. Everyone seemed to have a chip on his shoulder, and the animals were mean and rebellious when driven in for the hobbles to be removed and picket ropes substituted to hold them. Breakfast at last over, the caravan was about to start when Tom went along his own division and called four men together.

"Last night you fellers quit yer posts an' slunk back ter yer wagons," he said, ominously. "Two of ye air tenderfeet, an' green ter this life; one is a trader an' th' other is an old hand on th' trail. You all ought ter know better. I'm lettin' ye off easy this time, but th' next man that breaks guard is goin' ter git a cussed fine lickin'. If it's necessary I'll make an invalid out o' any man in my squad that sneaks off his post. Git back ter yer wagons, an' don't fergit what I've said."

The tenderfeet were pugnacious, but doubtful of their ground; the trader was abashed by the keen knowledge of his guilt and the enormity of his offense. He was a just man and had no retort to make. The teamster, a bully and a rough, with a reputation to maintain, scowled around the closely packed circle, looking for sympathy, and found plenty of it because the crowd was anxious to see the corporal, as personifying authority, soundly thrashed. They felt that no one had any right to expect a man to stand guard in such a rain out in the cheerless dark for two hours, especially when it was admitted that there was no danger to be feared. Finding encouragement to justify his attitude, and eager to wipe out the sting of the lecture, the bully grinned nastily and took a step forward.

"Reg'lar pit-cock, ain't ye?" he sneered. "High an' mighty with yer mouth, ain't ye? Goin' ter boss things right up ter th' hilt, you air! Wall, ye—I'm wettin' yer primin', hyar an'——"

Tom stopped the words with a left on the mouth, and while the fight lasted it was fast and furious; but clumsy brute strength, misdirected by a blind rage, could not cope with a greater strength, trained, agile, and cool; neither could a liquor soaked carcass for long take the heavy punishment that Tom methodically was giving it and come back for more. As the bullwhacker went down in the mud for the fifth time, there was a finality about the fall that caused his conqueror to wheel abruptly from him and face the ring of eager and disappointed faces.

"I warn't too busy ter hear some o' th' remarks," he snarled. "Now's th' time ter back 'em up! If ye don't it makes a double liar out o' ye! Come on—step out, an' git it over quick!" He glanced at the two pugnacious tenderfeet. "You two make about one man, th' way we rate 'em out hyar; come on, both o' ye!"

While they hesitated, Captain Woodson pushed through the crowd into the ring, closely followed by Tom's grim and silent friends, and a slender Mexican, the latter obviously solicitous about Tom's welfare. In a few moments the excitement died down and the crowd dispersed to its various wagons and pack animals. As Tom went toward his mules he saw Franklin, the tough officer of the third division, facing a small group of his own friends, and suddenly placing his hand against the face of one of them, pushed the man off his balance.

"I'll cut yer spurs," Franklin declared. "Fust man sneaks off guard in my gang will wish ter G-d he didn't!" He turned away and met Tom face to face. "We'll larn 'em, Boyd," he growled. "I'm aimin' ter bust th' back o' th' first kiyote of my gang that leaves his post unwatched. If one o' them gits laid up fer th' rest o' th' trip th' others'll stand ter it, rain or no rain. Ye should 'a' kicked in his ribs while ye had 'im down!"

After a confused and dilatory start the two trains strung out over the prairie and went on again; but the rebellious wagon-owners on the east side of the creek were not with the caravan. They were learning their lesson.

The heavy rain had swollen the waters of the stream, stirred up its soft bed and turned its banks into treacherous inclines slippery with mud. When the mean-spirited teams had been hooked to the wagons and sullenly obeyed the commands to move, they balked in mid-stream and would not cross it in their "cold collars;" and there they remained, halfway over. In vain the drivers shouted and swore and whipped; in vain they pleaded and in vain they called for help. The main part of the caravan, for once united in spirit, perhaps because it was a mean one, went on without them, knowing that the recalcitrant rear guard was in no danger; the sullen spirit of meanness in every heart rejoicing in the lesson being learned by their stubborn fellow travelers. The captain would have held up the whole train to give necessary assistance to any unfortunate wagoner; but there was no necessary assistance required here, for they could extricate themselves if they went about it right; and there was a much-needed lesson to be assimilated. Their predicament secretly pleased every member of the main body, which was somewhat humorous, when it is considered that the great majority of the men in the main body had no scruples against disobeying any order that did not suit their mood.

Finally, enraged by being left behind, the stubborn wagoners remembered one of the reasons advanced by the captain the day before when he had urged them to cross over and complete the corral. He had spoken of the difficulty of getting the animals to attempt a hard pull in "cold collars," when they would do the work without pausing while they were "warmed up." So after considerable eloquence and persistent urging had availed them naught, the disgruntled wagoners jumped into the cold water, waded to the head of the teams and, turning them around, got them back onto the bank they had left after vainly trying to lead them across. Once out of the creek, the teams were driven over a circle a mile in circumference to get their "collars warm." Approaching the creek at a good pace, the teams crossed it without pausing and slipped and floundered up the muddy bank at the imminent risk of overturning the wagons. Reaching the top, they started after the plodding caravan and in due time overtook it and found their allotted places in the lines, to some little sarcastic laughter. Never after that did those wagoners refuse to cross any stream at camp time, while their teams were warmed up and willing to pull; but instead of giving the captain any credit for his urging and his arguments, wasted the day before, they blamed him for going on without them, and nursed a grudge against him and his officers that showed itself at times until the end of the long journey. They would not let themselves believe that he would have refused really to desert them.

The caravan made only fifteen miles and camped on a rise of the open prairie, where practice was obtained in forming a circular corral, with the two cannons on the crest of the rise. The evolution was performed with snap and precision, the sun having appeared in mid-forenoon and restored the sullen spirits to natural buoyancy. The first squad of the watch went on duty with military promptness, much to the surprise of the more experienced travelers. Here for the first time was adopted a system of grazing which was a hobby with the captain, who believed that hobbled animals wasted too much time in picking and choosing the best grass and

Comments (0)