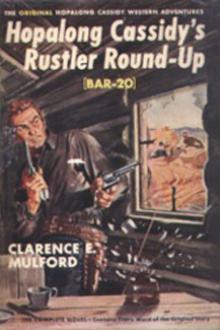

''Bring Me His Ears'' by Clarence E. Mulford (howl and other poems TXT) 📕

"I know how you feel, Mr. Boyd. Have you seen your father since you landed?"

Tom reluctantly shook his head. "It would only reopen the old bitterness and lead to further estrangement. No man shall ever speak to me again as he did--not even him. If you should see him, Jarvis, tell him I asked you to assure him of my affection."

"I shall be glad to do that," replied the clerk. "You missed him by only two days. He asked for you and wished you success, and said your home was open to you when you returned to resume your studies. I think, in his heart, he is proud of you, but too stubborn to admit it." As he spoke he chanced to glance through the window of the store. "Don't look around," he warned. "I want to tell you t

Read free book «''Bring Me His Ears'' by Clarence E. Mulford (howl and other poems TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Clarence E. Mulford

- Performer: -

Read book online «''Bring Me His Ears'' by Clarence E. Mulford (howl and other poems TXT) 📕». Author - Clarence E. Mulford

As they jogged on, a strip of timber running almost at right angles to their course and thinning out to the north in about the same proportion that it thickened to the south, came in sight and Tom knew it to be Cottonwood Creek, and their last glimpse of the waters of the Neosho. He well remembered the somewhat sharp bend formed by it on the farther side, which was taken advantage of by some caravans and the corral formation ignored. A line of closely spaced wagons across the neck of the bend made corral enough.

"Well, we better get back to the caravan," he said. "While the creek is all right there are many who are only waiting for a chance to cry that the officers are remiss in their duties. I'll leave you with your uncle, well guarded by six trusty knights, and go ahead with the advance guard."

She glanced at him out of the corner of her eye and the repression of her smile did not seriously affect the witchery of the dimples.

"I was a little afraid that I might become lonesome on this long journey; but things have turned out splendidly. Don't you think Dr. Whiting has a very distinguished air?"

"Very; it would distinguish him out of hundreds," replied Tom, scowling at the timber fringe ahead. "He is quite impressive when he is silent. It's a pity he doesn't realize it."

He turned in the saddle and looked behind. "What did I say? There comes Hank, with an antelope slung before his saddle. I doubt if the doctor would need the red handkerchief; antelope are notoriously affected by anything curious."

She turned away and regarded the caravan studiously. "Isn't every man expected to do his share in the general duties?" she asked.

"Yes; but most of them dodge obligations. When we left Council Grove more than half of the members of the train were friendly to Woodson. By the time we leave Cimarron his friends will be counted on the fingers of your two hands. That is only what he expects, so it won't come as an unpleasant surprise."

"What is the doctor's party supposed to do?"

"Two of them have been assigned to the rear guard; the other four, to our right flank. They can be excused somewhat because of their greenness. Besides, they only came along for the fun of it. In the college of life they are only freshmen. Its seriousness hasn't sunk in yet. The majority of the shirkers should know better, and have their fortunes, meagre as they may be, at stake. Well, here we are. You don't know how much I've enjoyed our ride. Uncle Joe," he said as Patience settled into the wagon seat, "here she is, safe and sound. I'll drop around with some antelope meat by the time you have your fire going."

"It's been ten years since I've broiled game over a fire," chuckled the driver. "I'm anxious to get my hand in again. Thank you, Tom."

Tom fastened the horse to the rear of the wagon, waved to his friends, and loped ahead toward the nearing creek.

CHAPTER XIINDIAN COUNTRY

After an enjoyable supper of antelope meat, Hank Marshall drifted over to visit Zeb Houghton and Jim Ogden, and judging from the hilarity resulting from his call, it was very successful. The caravan was now approaching the Indian country and was not very far from the easternmost point where traders had experienced Indian deviltry. Neither he nor his friends were satisfied with the way guard was kept at night, and he believed that a little example was worth a deal of precept. On his way back to his own part of the encampment he dropped over to pay a short visit to some tenderfeet, two of whom were to mount guard that night. Jim Ogden, sauntering past, discovered him and wandered over to borrow a pipeful of tobacco.

"Wall," said Ogden, seating himself before the cheerful fire, "'twon't be long now afore we git inter buffaler country, an' kin eat food as is food. Arter ye sink yer teeth inter fat cow an' chaw a tongue or two, ye'll shore forgit what settlement beef tastes like. That right, Hank?"

"It's shore amazin' how much roast hump ribs a man kin store away without feelin' it," replied Hank. "But thar's allus one drawback ter gittin' inter th' buffaler range; whar ye find buffaler ye find Injuns, an' nobody kin tell what an Injun's goin' ter do. If they only try ter stampede yer critters yer gittin' off easy. Take a Pawnee war-party, headin' fer th' Comanche or Kiowa country, fer instance. Thar off fer ter steal hosses; but thar primed ter fight. If thar strong enough a caravan'll look good ter 'em. One thing ye want ter remember: if th' Injuns ain't strong, don't ye pull trigger too quick; as long as yer rifle's loaded thar'll be plumb respectful, but soon's she's empty, look out."

"I've been expecting to see them before this," said one of the hosts.

"Wall, from now on mebby ye won't have ter strain yer eyes," Hank remarked. "They like these hyar timber fringes, whar they kin sneak right up under yer nose. They got one thing in thar favor, in attackin' at night; th' twang o' a bowstring ain't heard very fur; but onct ye hear it ye'll never fergit th' sound. Ain't that so, Jim?"

Jim nodded. "Fer one, I'm keepin' an eye open from now on. Wall, reckon I'll be movin' on."

"Where do you expect to run into Indians?" asked one of the men near the fire.

Jim paused, half turned and seemed to be reflecting. "'Most any time, now. Shore ter git signs o' 'em at th' little Arkansas, couple o' days from now. May run inter 'em at Turkey Creek, tomorrow night."

Hank arose, emptied his pipe, and looked at Jim. "Jine ye, fur's our fire," he said, and the two friends strolled away. They had not been gone long when two shadowy figures met and stopped not far from the tenderfeet's fire, and held a low-voiced conversation, none of which, however, was too low to be overheard at the fire.

"How'd'y, Tom."

"How'd'y, Zeb."

"On watch ter night?"

"No; you?"

"No. Glad of it."

"Me, too."

"This is whar Taos Bill war sculped, ain't it?"

"They killed 'im but didn't git his ha'r."

"How'd it happen?"

"Owl screeched an' a wolf howled. Bill snuk off ter find out about it."

"Arrer pizened?"

"Yes; usually air."

"Whar ye goin'?"

"Ter th' crick fer water."

"I'm goin' ter see th' capting. Good night."

"Good night; wish it war good mornin', Zeb."

"Me, too. Good night."

At that instant an owl screeched, the quavering, eerie sound softened by distance.

"Hear that?"

The mournful sound of a wolf floated through the little valley.

"An' that? Wolves don't generally answer owls, do they?"

"Come along ter th' crick, Zeb. Thar ain't no tellin'."

"I'm with ye," and the two figures moved silently away.

The silence around the camp-fire was profound and reflective, but there was some squirming and surreptitious examination of caps and flints. The questioning call of the hoot owl was answered by a weird, uncanny, succession of sharp barks growing closer and faster, ending in a mournful, high-pitched, long-drawn, quavering howl. The noisy activity of the encampment became momentarily slowed and then went on again.

The first guard came off duty with an apparent sense of relief and grew very loquacious. One of them joined the silent circle of tenderfeet around the blazing fire.

"Phew!" he grunted as he sat down. "Hear those calls?" His question remained unanswered, but he did not seem surprised. "When you go on, Doc?" he asked.

"One o'clock," answered Dr. Whiting. He looked around pityingly. "Calls?" he sneered. "Don't you know an owl or a wolf when you hear one?" There was a lack of sincerity in his voice which could not be disguised. The doctor was like the boy who whistled when going through the woods.

Midnight came and went, and half an hour later the corporal of the next watch rooted out his men and led them off to relieve the present guard. He cautioned them again against standing up.

"To a Injun's eyes a man standin' up on th' prairie is as plain as Chimbly Rock," he asserted. "Besides, ye kin see a hull lot better if yer eyes air clost ter th' ground, lookin' agin' th' horizon. Don't git narvous, an' don't throw th' camp inter a scare about nothin'."

An hour later an owl hooted very close to Dr. Whiting and he sprang to his feet. As he did so he heard the remarkably well imitated twang of a bowstring, and his imagination supplied his own interpretation to the sound passing his ear. Before he could collect his panic-stricken senses he was seized from behind and a moment later, bound with rawhide and gagged with buckskin, he lay on his back. A rough hand seized his hair at the same instant that something cold touched his scalp. At that moment his attacker sneezed, and a rough, tense voice growled a challenge from the darkness behind him.

"Who's thar?" called Tom Boyd, the clicking of his rifle hammers sharp and ominous.

The hand clutching the doctor's hair released it and the action was followed by a soft and hurried movement through the woods.

"Who's thar?" came the low growl again, as Tom crept into the bound man's range of vision and peered into the blackness of the woods. Waiting a moment, the plainsman muttered something about being mistaken, and departed silently.

After an agony of suspense, the bound man heard the approach of another figure, and soon the corporal of his guard stopped near him and swore vengefully under his breath as his soft query brought no answer.

"Cuss him," growled Ogden, angrily. "He's snuk back ter camp. I'll peg his pelt out ter dry, come daylight." He moved forward to continue his round of inspection and stumbled over the doctor's prostrate form. In a flash the corporal's knife was at the doctor's throat. "Who air ye?" he demanded fiercely. The throaty, jumbled growls and gurgles which answered him apprised him of the situation, and he lost no time in removing the gag and cutting the thongs which bound the sentry. "Thar, now," he said in a whisper. "Tell me about it."

The doctor's account was vivid and earnest and one of his hands was pressed convulsively against his scalp as if he feared it would leave him.

Ogden heard him through patiently, grunting affirmatively from time to time. "Jest what I told th' boys," he commented. "Wall, I reckon they war scared away. Couldn't 'a' been many, or they'd 'a' rushed us. It war a scatterin' bunch o' bucks, lookin' fer a easy sculp, or a chanct ter stampede th' animals. Thievin' Pawnees, I reckon. Mebby they'll come back ag'in: we'll wait right hyar fer 'em, dang thar eyes."

"Ain't you going to alarm the camp?" incredulously demanded the doctor, having hard work to keep his teeth from chattering.

"What in tarnation fer? Jest 'cause a couple o' young bucks nigh got yer h'ar? Hell, no; we'll wait right hyar an' git 'em if they come back."

"Do you think they will?" asked the doctor, trying to sound fierce and eager.

"Can't never tell what a Injun'll do. They left ye tied up, an' mebby want yer h'ar plumb bad. Reckon mebby I ought ter go 'round an' warn th' rest o' th' boys ter keep thar eyes peeled an' look sharp fer

Comments (0)