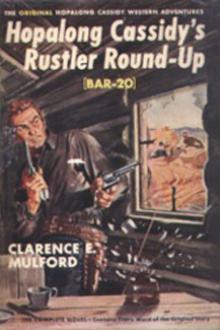

''Bring Me His Ears'' by Clarence E. Mulford (howl and other poems TXT) 📕

"I know how you feel, Mr. Boyd. Have you seen your father since you landed?"

Tom reluctantly shook his head. "It would only reopen the old bitterness and lead to further estrangement. No man shall ever speak to me again as he did--not even him. If you should see him, Jarvis, tell him I asked you to assure him of my affection."

"I shall be glad to do that," replied the clerk. "You missed him by only two days. He asked for you and wished you success, and said your home was open to you when you returned to resume your studies. I think, in his heart, he is proud of you, but too stubborn to admit it." As he spoke he chanced to glance through the window of the store. "Don't look around," he warned. "I want to tell you t

Read free book «''Bring Me His Ears'' by Clarence E. Mulford (howl and other poems TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Clarence E. Mulford

- Performer: -

Read book online «''Bring Me His Ears'' by Clarence E. Mulford (howl and other poems TXT) 📕». Author - Clarence E. Mulford

Hank Marshall got his fire started in a hurry while his partner looked after the pack mules; and when Tom came back to attend to the fire and prepare the supper, Hank dug into his "possible" sack and produced some line and a fish hook. Making a paste of flour, he mixed it with some dried moss he had put away and saved for this use. Rolling the little doughballs and hardening them over the fire he soon strode off up the creek, looking wise but saying nothing; and a quarter of an hour later he returned with three big catfish, one of which he ate after he had consumed a generous portion of buffalo hump-ribs; and he followed the fish by a large tongue raked out of the ashes of the fire. To judge from his expression he had enjoyed a successful and highly gratifying day, and since he was heavy and drowsy with his gorging and had to go on watch that night, he rolled up in his blanket under a wagon and despite the noise on all sides of him, fell instantly asleep. He had "set hisself" to awaken at eleven o'clock, which he would do almost on the minute and be thoroughly wide awake.

Fearing for the alertness of the sentries that night, a number of plainsmen and older traders agreed upon doing duty out of their turns and followed Hank's example, "settin'" themselves to awaken at different hours; and despite these precautions had a band of Pawnees discovered the camp that night they most certainly would have been blessed with success; and no one understood why the camp had not been discovered, for the crawling train made a mark on the prairie that could not be missed by savage eyes miles away.

Because of the height and the luxuriance of the grass within the corral the morning feeding, beyond the time needed for getting ready to leave, was dispensed with and the train got off to an early start, fairly embarked on the eastern part of the great buffalo range and a section of the trail where Indians could be looked for in formidable numbers.

This great plain fairly was crowded with bison and was dark with them as far as the eye could see. They could be numbered by the tens of thousands and actually impeded the progress of the caravan and threatened constant danger from their blind, unreasoning stampedes which the draft animals seemed anxious to join. Because of the matted hair in front of their eyes their vision was impaired; and the keenness of their scent often hurled them into dangers which a clearer eyesight would have avoided. So great did this danger become shortly after the train had left the valley of the Walnut that the rear guard, which had grown slightly as the days passed, now was sent out to protect the flanks and to strengthen the vanguard, which had fallen back within a few hundred feet of the leading wagons. Time after time the stupid beasts barely were kept from crashing blindly into the train, and the wagoners had the most trying and tiring day of the whole journey.

Several bands of Indians at times were seen in the distance pursuing their fleeing game, but all were apparently too busy to bother with the caravan, which they knew would stop somewhere for the night. No longer was there any need to freight buffalo meat to the wagons; for so many of the animals were killed directly ahead that the wagoners only had to check their teams and help each other butcher and load. This constant stopping, now one wagon and now another, threw the train out of all semblance of order and it wandered along the trail with its divisions mixed, which caused the sweat to stand out on the worried captain's forehead. His lieutenants threatened and swore and pleaded and at last, after the wagons had all they could carry of the meat, managed to get four passable divisions in somewhat presentable order.

While the caravan shuffled itself, chased buffalo out of the way, turned aside thundering ranks of the formidable-looking beasts, and had a time hectic enough to suit the most irrational, Pawnee Rock loomed steadily higher, steadily nearer, and the great sand-hills of the Arkansas stretched interminably into the West, each fantastic top a glare of dazzling light.

Well to the North, rising by degrees out of the prairie floor, and gradually growing higher and bolder as they neared the trail and the river, were a series of hills which terminated abruptly in a rocky cliff frowning down upon the rutted wagon road. From the distance the mirage magnified the ascending hills until they looked like some detached mountain range, which instead of growing higher as it was approached, shrunk instead. It was a famous landmark, silent witness of many bloody struggles, as famous on this trail as was Chimney Rock and Courthouse Rock along the great emigrant trail going up the Platte; but compared to them in height it was a dwarf. Here was a lofty perch from which the eagle eyes of Indian sentries could descry crawling caravans and pack trains, in either direction, hours before they reached the shadow of the rocky pile; and from where their calling smoke signals could be seen for miles around.

Two trails passed it, one east and west; the other, north and south. The former, cut deep, honest in its purpose and plainness, here crossed the latter, which was an evanescent, furtive trail, as befits a pathway to theft and bloodshed, and one made by shadowy raiders as they flitted to and from the Kiowa-Comanche country and the Pawnee-Cheyenne; only marked at intervals by the dragging ends of the lodgepoles of peacefully migrating Indian villages, and even then pregnant with danger. Other eyes than those of the prairie tribes had looked upon it, other blood had been spilled there, for distant as it was from the Apaches, and still more distant from the country of the Utes, war parties of both these tribes had accepted the gage of battle there flung down. On the rugged face of the rock itself human conceit had graven human names, and to be precise as to the date of their foolishness, had added day, month, and year.

While speaking of days, months, and years it may not be amiss to say that regarding the latter division of time the caravan was fortunate. Troubles between Indians and whites developed slowly during the history of the Trail, from the earlier days of the fur trains and the first of the traders' caravans, when Indian troubles were hardly more than an occasional attempted theft, in many cases successful, but seemingly without that lust for blood on both sides which was to come later. After the wagon period begun there was a slight increase, due to the need which certain white men found for shooting game. If game were scarce, what could be more interesting when secure from retaliation by the number of armed and resolute men in the caravans, than to pot-shoot some curious and friendly savage, or gallantly put to flight a handful of them? The ungrateful savages remembered these pleasantries and were prone to retaliate, which caused the death of quite a few honest and innocent whites who followed later. The natural cupidity of the Indian for horses, his standard of wealth, received a secondary urge, which later became the principal one, in the days when theft was regarded as a material reward for killing. While they may have grudged these periodic crossings of the plains as a trespass, and the wanton slaughter of their main food supply as a constantly-growing calamity, they still were keener to steal quietly and get away without bloodshed, and to barter their dried meat, their dressed hides, their beadwork, and other manufactures of their busy squaws than to engage in pitched battle at sight. Had Captain Woodson led a caravan along that same trail twenty or thirty years later, he would have had good reason to sweat copiously at the sight of so many dashing savages.

The captain knew the Indian of his day as well as a white man could. He knew that they still depended upon trading with the fur companies, with free trappers and free traders, and needed the white man's goods and good will; they wanted his trinkets, his tobacco to mix with their inner bark of the red willow; his powder, muskets, and lead, and, most of all, his watered alcohol. He knew that a white man could stumble into the average Indian camp and receive food and shelter, especially among those tribes not yet prostituted by contact with the frontier; that such a man's goods would be safe and, if he minded his own business, that he would be sent on his way again unharmed. But he also knew their lust for horses and mules; he felt their slowly growing feeling of contempt for men who would trade them wonderful things for worthless beaver, mink, and otter skins; and a fortune in trade goods for the pelt of a single silver fox, which neither was warmer nor more durable than the pelt of other foxes. And he knew the panicky feeling of self-preservation which might cause some greenhorn of the caravan to shoot true at the wrong time. So, without worrying about any "deadly circles" or about any period of time a score or more years away, he sweat right heartily. And when at last he drew near to Ash Creek, the later history of which mercifully was spared him, he sighed with relief but worked with the energy befitting a man who believed that God helped those who helped themselves; he hustled the caravan down the slope and across the stream with a speed not to be lightly scorned when the disorganized arrangement of the train is considered; and he halted the divisions in a circular formation with great dispatch, making it the most compact and solid wall of wagons seen so far on the journey.

CHAPTER XIIPAWNEES

At this Ash Creek camp before the wagoners had unhitched their teams there was a cordon around the corral made up of every man who could be spared, and the cannon crews stood silently around their freshly primed guns. The air of tenseness and expectancy pleased Woodson, for it was an assurance that there would be no laxity about this night's watch. With the animals staked as close to the wagons as practicable, which caused some encroachments and several fist fights between jealous wagoners, the fires soon were cooking supper for squads of men from the sentry line; and as soon as all had eaten and the camp was not distracted by too many duties, the cordon thinned until it was composed of a double watch. Before

Comments (0)