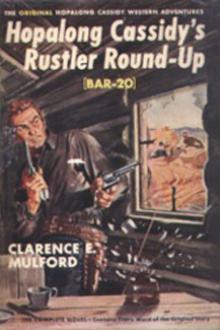

''Bring Me His Ears'' by Clarence E. Mulford (howl and other poems TXT) 📕

"I know how you feel, Mr. Boyd. Have you seen your father since you landed?"

Tom reluctantly shook his head. "It would only reopen the old bitterness and lead to further estrangement. No man shall ever speak to me again as he did--not even him. If you should see him, Jarvis, tell him I asked you to assure him of my affection."

"I shall be glad to do that," replied the clerk. "You missed him by only two days. He asked for you and wished you success, and said your home was open to you when you returned to resume your studies. I think, in his heart, he is proud of you, but too stubborn to admit it." As he spoke he chanced to glance through the window of the store. "Don't look around," he warned. "I want to tell you t

Read free book «''Bring Me His Ears'' by Clarence E. Mulford (howl and other poems TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Clarence E. Mulford

- Performer: -

Read book online «''Bring Me His Ears'' by Clarence E. Mulford (howl and other poems TXT) 📕». Author - Clarence E. Mulford

It was not yet noon when the advance guard came upon an unusual sight. The plain was torn and scored and covered with sheepskin saddle-pads, broken riding gear, battered and discarded firelocks of so ancient a vintage that it were doubtful whether they would be as dangerous to an enemy as they might be to their owners; broken lances, bows and arrows, torn clothing, a two-wheeled cart overturned and partly burned, and half a score dead mules and horses.

Captain Woodson looked from the strewed ground, around the faces of his companions.

"Injuns an' greasers?" he asked, glancing at the remains of the carreta in explanation of the "greaser" end of the couplet. The replies were affirmative in nature until Tom Boyd, looking fixedly at one remnant of clothing, swept it from the ground and regarded it in amazement. Without a word he passed it on to Hank, who eyed it knowingly and sent it along.

"I'm bettin' th' Texans licked 'em good," growled Tom. "It's about time somebody paid 'em fer that damnable, two thousand mile trail o' sufferin' an' death! Wish I'd had a hand in this fight!"

Assenting murmurs came from the hunters and trappers, all of whom would have been happy to have pulled trigger with the wearers of the coats with the Lone Star buttons.

Tom shook his head after a moment's reflection. "Hope it war reg'lar greaser troops an' not poor devils pressed inter service. That's th' worst o' takin' revenge; ye likely take it out o' th' hides of them that ain't to blame, an' th' guilty dogs ain't hurt."

"Mebby Salezar war leadin' 'em!" growled Hank. "Hope so!"

"Hope not!" snapped Tom, his eyes glinting. "I want Salezar! I want him in my two hands, with plenty o' time an' nobody around! I'd as soon have him as Armijo!"

"Who's he?" asked a tenderfoot. "And what about the Texans, and this fight here?"

"He's the greaser cur that had charge o' th' Texan prisoners from Santa Fe to El Paso, where they war turned over to a gentleman an' a Christian," answered Tom, his face tense. "I owe him fer th' death, by starvation an' abuse, of as good a friend as any man ever had: an' if I git my hands on him he'll pay fer it! That's who he is!"

The first day's travel across the dry stretch, notwithstanding the start had been later than was hoped for, rolled off more than twenty miles of the flat, monotonous plain. Even here the grama grass was not entirely missing, and a nooning of two hours was taken to let the animals crop as much of it as they could find. While the caravan was now getting onto the fringe of the Kiowa and Comanche country, trouble with these tribes, at this time of the year, was not expected until the Cimarron was reached and for this reason the urging for mileage was allowed to keep the wagons moving until dark. During the night the wagoners arose several times to change the picket stakes of their animals, hoping by this and by lengthened ropes to make up for the scantiness of the grass. In one other way was the sparsity of the grazing partly made up, for the grama grass was a concentrated food, its small seed capsules reputed to contain a nourishment approaching that of oats of the same size.

The heat of the day had been oppressive and the contents of the water casks were showing the effects of it. The feather-headed or stubborn know-it-alls who had ignored the call of "water scrape" back on the bank of the Arkansas now were humble pilgrims begging for drinks from their more provident companions. Tom and Hank had filled their ten-gallon casks and put them in Joe Cooper's wagons for the use of his and their animals which, being mules, found a dry journey less trying than the heavy-footed oxen of other teams. The mules also showed an ability far beyond their horned draft fellows in picking up sufficient food; they also were free from the foot troubles which now began to be shown by the oxen. The triumphant wagoners of the muddier portions of the trail, whose oxen had caused them to exult by the way they had out-pulled the mules in every mire, now became thoughtful and lost their levity.

Breakfast was cooked and eaten before daylight and the wagons were strung out in the four column formation before dawn streaked the sky. A few buffalo wallows, half full of water from the recent rains, relieved the situation, and the thirsty animals emptied their slightly alkaline contents to the last obtainable drop. This second day found the plain more barren, more desolate, its flat floor apparently interminable, and the second night camp was not made until after dark, the wagons corralling by the aid of candle lanterns slung from their rear axles. It was a silent camp, lacking laughter and high-pitched voices; and the begging water seekers, while not denied their drinks, were received with a sullenness which was eloquent. One of them was moved to complain querulously to Tom Boyd of the treatment he had received at one wagon, and forthwith learned a few facts about himself and his kind.

"Look hyar," drawled Tom in his best frontier dialect. "If I war runnin' this caravan yer tongue would be hangin' out fer th' want o' a drink. You war warned, fair an' squar, back on th' Arkansas, ter carry all th' water ye could. But ye knew it all, jest like ye know it all every time a better man gives ye an order. If it warn't fer yer kind th' Injuns along th' trail would be friendly. Hyar, let me tell ye somethin':

"We been follerin', day after day, a plain trail, so plain that even you could foller it. But thar was a time when thar warn't no trail, but jest an unmarked plain, without a landmark, level as it is now, all 'round fur's th' eye could reach. Thar warn't much knowed about it years ago, an' sometimes a caravan wandered 'round out hyar, its water gone an' th' men an' animals slowly dyin' fer a drink. Some said go this way, some said to go that way; others, other ways. Nobody knowed which war right, an' so they went every-which way, addin' mile to mile in thar wanderin'. Then they blindly stumbled onter th' Cimarron, which they had ter do if they follered thar compasses an' kept on goin' south; an' when they got thar they found it dry! Do ye understand that? They found th' river dry! Jest a river bed o' sand, mile after mile, dry as a bone.

"Which way should they go? It warn't a question then, o' headin' fer Santa Fe; but o' headin' any way a-tall ter git ter th' nearest water. If they went down they was as bad off as if they went up, fer th' bed war dry fer miles either way in a dry season. Sufferin'? Hell! you don't know what sufferin' is! A few o' you fools air thirsty, but yer beggin' gits ye water. Suppose thar warn't no water a-tall in th' hull caravan, fer men, wimmin, children, or animals? Suppose ye war so thirsty that you'd drink what ye found in th' innards o' some ol' buffalo yer war lucky enough ter kill, an' near commit murder ter git furst chanct at it? That war done onct. Don't ye let me hear ye bellerin' about bein' thirsty! Suppose we all had done like you, back thar on th' Arkansas? An' don't ye come ter us fer water! If we had bar'ls o' it, we'd pour it out under yer nose afore we'd give ye a mouthful! Yer larnin' some lessons this hyar trip, but yer larnin' 'em too late. Go 'bout yer business an' think things over. We're comin' ter bad Injun country. If ye got airy sense a-tall in yer chuckle head ye'll mebby have a chanct ter show it."

Before noon on the third day, after crossing more broken country which was cut up with many dry washes through which the wagons wallowed in imminent danger of being wrecked, the caravan came to the Cimarron, and found it dry. Cries of consternation broke out on all sides, and were followed by dogmatic denials that it was the Cimarron. The arguments waged hotly between those who were making their first trip and the more experienced traders. Who ever heard of a dry river? This was only another dry wash, wider and longer, but only a wash. The Cimarron lay beyond.

Here ensued the most serious of all the disagreements, for a large number of the members of the caravans scoffed when told that by following the plain wagon tracks they would soon reach the lower spring of the Cimarron. How could the spring be found when this was not the Cimarron River at all? They knew that when Woodson had been elected at Council Grove that he was not fitted to take charge of the caravan; that his officers were incompetent, and now they were sure of it. Anyone with sense could see that this was no river. If it were a river, then the prairie-dog mounds they had just passed were mountains. Here was a situation which needed more than tact, for if the doubting minority was allowed to follow their inclinations they might find a terrible death at the end of their wanderings. Dogmatic and pugnacious, almost hysterical in their repeated determination to go on and find the river, they must be saved, by force if necessary, from themselves. They would not listen to the plea that they go on a few miles and let the spring prove them to be wrong; there was no spring to be found in a few miles if it was located on the Cimarron. Woodson and others argued, begged, and at last threatened. They pointed out that they were familiar with every foot of the trail from one end to the other; that they had made the journey year after year, spring and fall; that here was the deeply cut trail, pointing out the way to water, where other wagons had rolled before them, following the plain and unequivocal tracks. The debate was growing noisier and more heated when Tom stepped forward and raised his hand.

"Listen!" he shouted again and again, and at last was given a grudged hearing. "Let's prove this question, for it's a mighty serious one," he cried. "Last year, where th' trail hit th' Cimarron, which had some water in it then, a team of mules, frantic from thirst, ran away with a Dearborn carriage as the driver was getting out. When we came up with them we found one of them with a broken leg, struggling in the wreckage of the carriage. I have not been out of your sight all morning, and if I tell you where to find that wrecked carriage, and you do find it, you'll know that I'm tellin' th' truth, an' that this is th' Cimarron. Go along this bank, about four hundred yards, an' you'll find a steep-walled ravine some thirty feet higher than th' bed of th' river. At th' bottom of it, a hundred yards from th' river bank, you'll find what's left of th' Dearborn. When you come back we'll show you how to relieve your thirst and to get enough water to let you risk goin' on to th' spring."

Sneers and ridicule replied to him, but a skeptical crowd,

Comments (0)