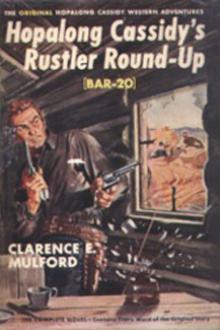

''Bring Me His Ears'' by Clarence E. Mulford (howl and other poems TXT) 📕

"I know how you feel, Mr. Boyd. Have you seen your father since you landed?"

Tom reluctantly shook his head. "It would only reopen the old bitterness and lead to further estrangement. No man shall ever speak to me again as he did--not even him. If you should see him, Jarvis, tell him I asked you to assure him of my affection."

"I shall be glad to do that," replied the clerk. "You missed him by only two days. He asked for you and wished you success, and said your home was open to you when you returned to resume your studies. I think, in his heart, he is proud of you, but too stubborn to admit it." As he spoke he chanced to glance through the window of the store. "Don't look around," he warned. "I want to tell you t

Read free book «''Bring Me His Ears'' by Clarence E. Mulford (howl and other poems TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Clarence E. Mulford

- Performer: -

Read book online «''Bring Me His Ears'' by Clarence E. Mulford (howl and other poems TXT) 📕». Author - Clarence E. Mulford

"Our village on the Washita is no more," said a chief who had enough long hair to supply any hirsute deficiency of a dozen men and not suffer by it. "Its ashes are blown by the winds and its smoke brings tears to the eyes of our squaws and children. Our winter maize is gone and our storehouses lie about the ground. White Buffalo and his braves were hunting the buffalo beyond the Cimarron. Their old men and their squaws and children were with them. Some of my young men have just returned and brought us this news. What have the white men to say of this?"

"Our hearts are heavy for our friends the Comanches," answered Woodson. "There are many tribes of white men, as there are many tribes of Indians. There are the Americanos, the Mexicanos, the Englise, and the Tejanos. The Americans come from the North and the East along their great trail, with goods to trade and with friendship for the Comanches. The Mexicanos would not dare to burn a Comanche village; but with the Tejanos are not the Comanches at war? And we have seen Tejanos near the trail. We have seen where they defeated Armijo's soldiers, almost within sight of the Arkansas River. Cannot White Buffalo read the signs on the earth? Our trail is plain for many days to the east, for all to see. Has he seen our wagon tracks to the Washita? Are his young men blind? We are many and strong and have thunder guns, but we do not fight except to protect ourselves and our goods. We are traders."

"We are warriors!" exclaimed the chief. "We also are many and strong, and our lances are short that our courage may be long. White Buffalo has listened. He believes that the white chief speaks with a single tongue. His warriors want the white man's guns and powder; medicine guns that shoot like the clapping of hands. Such have the Tejanos. He has skins and meat and mulos."

"The medicine guns are Tejano medicine," replied Woodson. "We have only such as I see in the hands of some of our friends, the Comanches. Powder and lead we have little, for we have come far and killed much game; blue and red cloth we have, medicine glasses, beads, awls, knives, tobacco, and firewater we have much of. Our mules are strong and we need no more." He looked shrewdly at a much-bedecked Indian at the chief's side. "We have presents for the Comanche Medicine Man that only his eyes may see."

The medicine man's face did not change a muscle but there came a gleam to his eyes that Woodson noted.

"The Comanches are not like the Pawnees or Cheyennes to kill their eyes and ears with firewater," retorted the chief. "We are not Pawnee dogs that we must hide from ourselves and see things that are not. Our hair is long, that those may take it who can. I have spoken."

There was some further talk in which was arranged a visit from the Comanche chief; the bartering price of mules, skins, and meat, as was the custom of this tribe; a long-winded exchange of compliments and assurances of love and good will, in the latter both sides making plenty of reservations.

When Woodson and his companions returned to the encampment they went among the members of the caravan with explicit instructions, hoping by the use of tact and common sense to avert friction with their expected visitors. Small articles were put away and the wagon covers tightly drawn to minimize the opportunities of the Indians for theft.

The night passed quietly and the doubled guard apparently was wasted. Shortly after daylight the opposite hill suddenly swarmed with dashing warriors, whose horsemanship was a revelation to some of the tenderfeet. Following the warriors came the non-combatants of the tribe, pouring down the slope in noisy confusion. Woodson swore under his breath as he saw the moving village enter the shallow waters of the river to camp on the same side with the caravan, for it seemed that his flowery assurances of love and esteem had been taken at their face value; but he was too wise to credit this, knowing that Indians were quick to take advantage of any excuse that furthered their ends. The closer together the two camps were the more easily could the Indians over-run the corralled traders.

Reaching the encampment's side of the stream the lodges were erected with most praiseworthy speed, laid out in rows, and the work finished in a remarkably short time. The conical lodges averaged more than a dozen feet in diameter and some of them, notably that of the chief, were somewhere near twice that size.

In the middle of the morning the chiefs and the more important warriors paid their visit to the corral and were at once put in good spirits by a salute from the cannons, a passing of the red-stone pipes, and by receiving presents of tobacco and trade goods. While they sat on the ground before Woodson's wagon and smoked, the medicine man seemed restless and finally arose to wander about. He bumped into Tom Boyd, who had been waiting to see him alone, and was quickly led to Franklin's wagon where the owner, hiding his laughter, was waiting. It is well to have the good will of the chiefs, but it is better also to have that of the medicine man; and wily Hank Marshall never overlooked that end of it when on a trading expedition among the Indians. He had let Woodson into his secret before the parley of the day before, and now his scheme was about to bear fruit.

Franklin made some mysterious passes over a little pile of goods which was covered with a gaudy red cloth on which had been fastened some beads and tinsel; and as he did so, both Tom and Hank knelt and bowed their heads. Franklin stepped back as if fearful of instant destruction, and then turned to the medicine man, who had overlooked nothing, with an expression of reverent awe on his face.

For the next few minutes Franklin did very well, considering that he knew very little of what he was talking about, but he managed to convey the information that under the red cloth was great medicine, found near the "Thunderer's Nest," not far from the great and sacred red pipestone quarry of the far north. The mention of this Mecca of the Indians, sacred in almost every system of Indian mythology, made a great impression on the medicine man and it was all he could do to keep his avaricious fingers off the cloth and wait until Franklin's discourse was finished. The orator wound up almost in a whisper.

"Here is a sour water that has the power to foretell peace or war," he declaimed, tragically. "There are two powders, found by the chief of the Hurons, under the very nest of the Thunder Bird. They look alike, yet they are different. One has no taste and if it is put into some of the sour water the water sleeps and tells of peace; but if the other, which has a taste, is put in the medicine water, the water boils and cries for war. It is powerful medicine and always works."

The eyes of the red fakir gleamed, for with him often lay the decision as to peace or war, and in this respect his power was greater even than that of a chief. After a short demonstration with the water, to which had been added a few drops of acid, the two powders, one of which was soda, were tested out. The medicine man slipped his presents under his robe, placed his fingers on his lips and strode away. When the next Comanche war-council was held he would be a dominating figure, and the fame of his medicine would spread far and wide over the Indian country.

"Got him, body an' soul!" chuckled Franklin, rubbing his hands. "Did ye see his mean ol' eyes near pop out when she fizzed? He saw all th' rest o' th' stuff an' he won't rest till he gits it all; an' he won't git it all till his tribe or us has left. He plumb likes th' fizz combination, an' mebby would want to try it out hyar an' now. Thar won't be no trouble with these Injuns this trip."

"An' that thar black sand ye gave him," laughed Hank, leaning back against a wagon wheel, "that looks like powder, so he kin make his spell over real powder, slip th' sand in its place, an' show how his medicine will fix th' powder of thar enemies so it won't touch off! Did ye see th' grin on his leather face, when he savvied that? He's a wise ol' fakir, he is!"

Tom grinned at Franklin. "Hank, here, has got th' medicine men o' th' Piegan Blackfeet eatin' out o' his hand. Every time th' Crows git after him too danged hot he heads fer th' Blackfoot country. They only follered him thar onct. What all did ye give 'em, Hank?"

"Oh, lots o' little things," chuckled Hank, reminiscently. "Th' medicine men o' th' Blackfeet air th' greatest in th' world; thar ain't no others kin come within a mile o' 'em, thanks ter me an' a chemist I know back in St. Louie. Th' other traders allus git what I leave."

When the important Indian visitors left there was quite a little ceremony, and the camp was quiet until after the noon meal. Early in the afternoon, according to the agreement with the chief and the medicine man, the Indians visited the encampment in squads, and at no time was there more than thirty or forty savages in the encampment at once. Instead of the usual attempted stampede of the animals at night all was peaceful; and instead of having to remain for two or three days in camp, at all times in danger of a change in the mood of the savages, the caravan was permitted to leave on the following morning, which miracle threw Woodson into more or less of a daze. As the last wagon rounded a hillock several miles from the camp site a mounted Comanche rode out of the brush and went along the column until he espied Franklin; and a few moments later he rode into the brush again, a bulging red cloth bundle stowed under his highly ornamented robe.

But there was more than the desire to trade, the professed friendship and the bribery of the medicine man that operated for peace in the minds of the Comanches. Never so early in the history of the trail had they attacked any caravan as large as this one and got the best of the fight. In all the early years of the trail the white men killed in such encounters under such conditions, could be counted on the fingers of one hand; while the Indian losses had been considerable. With all their vaunted courage the Comanches early had learned the difference between Americans and Mexicans, and most of their attempts against large caravans had been more for the purpose of stampeding the animals than for fighting, and their efforts mostly had been "full of sound and fury," like Macbeth's idiot's tale,

Comments (0)