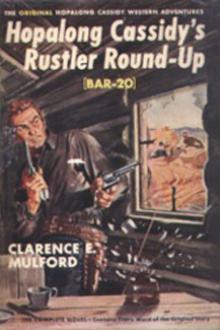

''Bring Me His Ears'' by Clarence E. Mulford (howl and other poems TXT) 📕

"I know how you feel, Mr. Boyd. Have you seen your father since you landed?"

Tom reluctantly shook his head. "It would only reopen the old bitterness and lead to further estrangement. No man shall ever speak to me again as he did--not even him. If you should see him, Jarvis, tell him I asked you to assure him of my affection."

"I shall be glad to do that," replied the clerk. "You missed him by only two days. He asked for you and wished you success, and said your home was open to you when you returned to resume your studies. I think, in his heart, he is proud of you, but too stubborn to admit it." As he spoke he chanced to glance through the window of the store. "Don't look around," he warned. "I want to tell you t

Read free book «''Bring Me His Ears'' by Clarence E. Mulford (howl and other poems TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Clarence E. Mulford

- Performer: -

Read book online «''Bring Me His Ears'' by Clarence E. Mulford (howl and other poems TXT) 📕». Author - Clarence E. Mulford

TEXAN SCOUTS

The day broke clear and the usual excitement and bustle of the camp was increased by the eager activities of the two hunting parties. After the morning meal the animals were driven some distance from the camp and the herd guards began their day's vigil. Tom placed the outposts and returned to report to the captain, and then added that he had something of a very confidential nature to tell him, but did not want to be seen talking too long with him.

Woodson reflected a moment. "All right; I'll come after ye in a few minutes an' ask ye ter go huntin' with me. 'Twon't be onusual if we ketch th' fever, too."

Tom nodded and went over to Cooper's wagons to pay his morning's respects, and to his chagrin found that Patience had gone for a short ride with Doctor Whiting and his friends.

"Sorry to miss her, Uncle Joe," he said. "Things are going to happen fast for me from now on. I may leave the caravan tonight. About two days' more travel and we'll be south of Bent's. Hank and I don't want to lose our merchandise, we can't take it with us, and we need to turn it into money. How much can you carry from here on?"

Uncle Joe scratched his head. "The two big wagons can take five hundred-weight more apiece, and this wagon can stand near eight hundred, seein' that it ain't carryin' much more than our personal belongings. Don't worry, Tom; if I can't handle it all, Alonzo and Enoch can take th' balance. Them greasers showing their cards?"

"It's like this: According to those Texans we met, no troops are going to meet us this trip. Their advance guard got thrashed and Armijo and the main body turned tail at Cold Spring and fled back to Santa Fe. I could go with the caravan miles farther and probably be safe; but if Pedro gets a messenger away secretly there is no telling what may happen. If I stay with the caravan and put up a fight it might end in embroiling a lot of the boys and certainly would make trouble for them if the train pushed on to Santa Fe, and it's got to push on. I won't surrender meekly. So, you see, I'll have to strike out."

Uncle Joe nodded. "If it wasn't for Patience, and my brother in Santa Fe, I'd strike out with you. Goin' to Bent's?"

"Bent's nothing!" retorted Tom. "I'm going to Santa Fe, but I'm going a way of my own."

"It's suicide, Tom," warned his friend. "Better let me take in your stuff, an' meet us here on the way back. Patience won't spoil; an' when she learns how much you're wanted by Armijo she'll worry herself sick if she knows you are in th' city. Don't you do it!"

Tom scowled at a break in the hills and in his mind's eye he could see her riding gaily with his tenderfoot rivals. "Reckon she won't fall away," he growled. "Anyhow, there's no telling; an' there's no reason why she should know anything. I told her I was goin' to Santa Fe, an' I'm going!"

Uncle Joe was about to retort but thought better of it and smiled instead. "Oh, these jealous lovers!" he chuckled. "Blind as bats! Who do you know there, in case I want to get word to you?"

Tom swiftly named three men and told where they could be found, his companion nodding sharply at the mention of two of them.

"Good!" exclaimed the trader. "Throw your packs into my wagons an' I'll see to stowin' 'em."

"No," replied Tom. "That's got to be done when th' camp's asleep. I'm supposed to be takin' 'em with me.

"But these Mexicans'll trail you, an' get you when you're asleep," objected Uncle Joe.

Tom laughed and shook his head, and turned to face Woodson, who was walking toward them. "Th' captain an' I am goin' huntin'. See you later."

"Git yer hoss, Boyd," called the captain. "I'm goin' fer mine now. How air ye, Mr. Cooper?"

"Never felt better in my life, captain. We all owe you a vote of thanks, an' I'll see that you get it."

"Thar ain't a man livin' as kin git a vote o' thanks fer me out o' this caravan," laughed Woodson, his eyes twinkling. "But I ain't got no call ter kick: I ain't had nigh th' trouble I figgered on. Jest th' same, I'll be glad when we meet up with th' greaser troops at Cold Spring. I aim to leave ye thar an' go on ahead an' fix things in th' city."

Uncle Joe caught himself in time. "That's where we bust up?"

Woodson nodded. "Thar ain't no organization from thar in. Don't need it, with th' sojers. All us proprietors that ain't got reg'lar connections in th' city will be leavin' from Cold Spring on."

"Any danger from th' Injuns, leavin' that way?"

"Oh, we slip out at night," answered Woodson. "Thar ain't much danger from any big bands. Got ter do it; customs officers air like axles; they work better arter they air greased. I aim ter leave two waggins behind th' noon arter we git to th' Upper Spring, an' save five hundred apiece on 'em. Th' other six kin make it from thar with th' extry loads, an' th' extry animals to help pull 'em." He looked toward the wagons of Alonzo and Enoch, where Tom had tarried on his way back. "Thar's a fine, upstandin' young man; I've had my eye on him ever since we left th' Grove."

"He is; an' anythin' he tells you is gospel," said Uncle Joe.

They saw the two traders waving their arms and soon Tom hurried up.

"Alonzo an' Enoch would like to go with us, only thar hosses air with th' herd," he said.

"Then we'll go afoot," declared Woodson. "I ain't hankerin' so much fer a hunt as I air ter git away from these danged waggins fer a spell. I'm sick o' th' sight o' 'em. Better come along, Mr. Cooper."

"That depends on how fur yer goin'; this young scamp will walk me off my feet."

"Oh, jest a-ways around th' hills; dassn't go too fur, on account of airy Injuns that may be hangin' 'round."

In a few moments the little group had left the encampment behind and out of sight and Woodson, waving the others ahead, fell back to Tom's side.

"Hyar we air, with nobody ter listen. What ye want ter tell me?"

To the captain's growing astonishment Tom rapidly sketched his conversation with the two Texans, his affair with the despotic New Mexican governor and what it now meant to him. Then he told of his determination to leave the caravan some night soon, perhaps on this night.

"Wall, dang my eyes!" exclaimed Woodson at the conclusion of the narrative. "Good fer them Texans! Young man, which hand did ye hit him with? That un? Wall, I'll jest shake it, fer luck." He thought a moment. "Ye air lucky, Boyd; north o' here, acrost th' headwaters o' this river, an' a couple more streams, which might be dry now, ye'll hit th' Picketwire, that's allus wet. If ye find th' little cricks dry, head more westward an' ye'll strike th' Picketwire quicker. It'll take ye nigh inter sight o' Bent's; an' thar ain't no finer men walkin' than William an' Charles Bent. Hate ter lose ye, Boyd; but thar ain't no two ways 'bout it; ye got ter go, or get skinned alive."

"I'm not goin' ter Bent's, captain," said Tom quietly. "I'll be in Santa Fe soon after you git thar. Hank knows them mountains like you know this trail. When I'm missed if ye'll throw 'em off my track I'll not fergit it." He smiled grimly. "If I war goin' ter Bent's they could foller, an' be damned to 'em. I'd like nothin' better than have 'em chase us through this kind o' country."

Woodson chuckled and then grew thoughtful. "Boyd, them Texans air goin' ter make trouble fer us, shore as shootin'. It'll be bad fer you, fer every American in these settlements is goin' ter be watched purty clost. Better go ter Bent's."

"Nope; Hank an' me air headin' fer Turley's, up on Arroyo Hondo. Hank knows him well. Hyar come th' others. I've told you an' Cooper, an' that's enough. You fellers ain't turnin' back so soon, air ye?" he called. "Ye don't call this a hunt? Whar's yer meat?"

"Whar's yourn?" countered Alonzo, grinning. "I ate so many berries I got cramps."

"Us, too," laughed Uncle Joe. "My feet air tender, ridin' so long. We're goin' back."

"Might as well jine ye, then," said Woodson. "Comin', Boyd?"

"Not fer awhile," answered Tom, pushing on.

He made his way along the lower levels, reveling in the solitude and the surroundings, and his keen eyes missed nothing. A mile from camp he suddenly stopped and carefully parted the thick berry bushes. In the soft soil were the prints of many horses, most of them shod. Cautiously he followed the tracks and in a few moments came to the edge of a small, heavily grassed clearing, so well hidden by the brush and the thick growth of the trees along the encircling, steep-faced hills that its presence hardly would be suspected. Closely cropped circles, each centered by the hole made by a picket pin, told him the story; and when he had located the sand-covered site of the fire, whose ashes and sticks carefully had been removed, an imprint in the soft clay brought a smile to his face.

"Following us close," he muttered. "Lord help any Mexicans that wander away from the wagons. Nearer twenty than what they said." He slipped along the edge of the pasture and found where the party had left the little ravine. Following the trail he soon came to another matted growth of underbrush, and then he heard the barely audible stamp of a horse. Creeping forward he wormed his way through the greener brush and finally peered through an opening among the stems and branches. A dozen Texans were lolling on the floor of the ravine, and he knew that the others were doing sentry duty.

A shadow passed him and he froze, and then relaxed as Burch came into sight. It was needful that he make no mistake in how he made his presence known, for a careless hail might draw a volley.

Burch passed him treading softly and when the man's back was turned to him Tom called out in a low voice. "Burch! Don't shoot!"

"Boyd!" exclaimed the sentry. "Cussed if ye ain't a good un, gittin' whar ye air an' me not knowin' it. What ye doin' hyar?"

"Scoutin' fer Injuns. Glad ter see ye."

Burch stepped to the edge of the ravine. "Friend o' mine comin' down, name o' Boyd." He turned. "Go down an' meet th' boys; thar honin' fer to shake han's with th' kiyote that hit Armijo. Be with ye soon."

Tom descended and shook hands with the smiling Texans and in a few moments was at home in the camp. He noticed that they all had the Colt revolving rifles which his friend Jarvis, back in St. Louis, had condemned. Each man wore two pistols of the same make, and most of them carried heavy skinning knives inside their boot legs.

"I heard tell them rifles warn't o' much account," he observed.

"Wall, they ain't as good as they might be," confessed a lanky Texan, "if thar used careless an' git too hot. A Hawken will out-shoot 'em; but we mostly fight on hossback, an' like ter git purty clost. Take them greasers we

Comments (0)