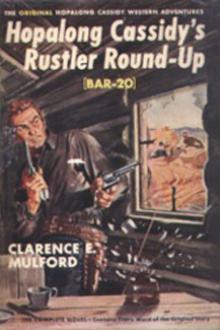

''Bring Me His Ears'' by Clarence E. Mulford (howl and other poems TXT) 📕

"I know how you feel, Mr. Boyd. Have you seen your father since you landed?"

Tom reluctantly shook his head. "It would only reopen the old bitterness and lead to further estrangement. No man shall ever speak to me again as he did--not even him. If you should see him, Jarvis, tell him I asked you to assure him of my affection."

"I shall be glad to do that," replied the clerk. "You missed him by only two days. He asked for you and wished you success, and said your home was open to you when you returned to resume your studies. I think, in his heart, he is proud of you, but too stubborn to admit it." As he spoke he chanced to glance through the window of the store. "Don't look around," he warned. "I want to tell you t

Read free book «''Bring Me His Ears'' by Clarence E. Mulford (howl and other poems TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Clarence E. Mulford

- Performer: -

Read book online «''Bring Me His Ears'' by Clarence E. Mulford (howl and other poems TXT) 📕». Author - Clarence E. Mulford

A low voice answered him and he shivered as a trickle of cold rain rolled down his face. "Thought you had given it up till tomorrow night. This is a hell of a night, boys, to go wandering off from the camp. Sure you won't get lost among th' hills?" He chuckled at the reply and shivered again. "Sure I'll tell her Bent's. Yes. No, she won't. What? Look here, young man; she's plumb cured of tenderfeet. Yes, I remember everything. All right; good luck, boys. God knows you'll need it!" He listened for a moment, heard no sounds of movement, and called again. "What's th' matter?" There came no answer and he crept back to his blankets, his teeth chattering, and lay awake the rest of the night, worrying.

Between the wagons and the road the little pack train waited, kept together by soft bird calls instead of by sight. A plaintive, disheartened snipe whistled close by and was answered in kind. Hank almost bumped into Ogden before he saw him. They both looked like drowned rats, the water slipping from the buffalo hair and pouring from them in little rills.

"Ain't a guard in sight, or ruther feelin', fifty feet each side o' th' road," Hank reported. "Bet every blasted one o' 'em is back in camp. Mules all tied together? Everybody hyar? All right. Off we go."

All night long the little atejo slopped down the streaming road, kept to it by the uncanny instinct and the oft repeated cheeping and twittering of the adopted son of the Blackfeet, who could perfectly imitate any night bird he ever had heard; and he had heard them all. Horses whinnied, mules brayed, wolves and coyotes howled, foxes squalled, chipmunks scolded, squirrels chattered and several other animals performed solos in the dark at the head of the little pack train, to be answered from the rear. Anyone unfortunate enough to be camped at the edge of the trail would have thought himself surrounded by a menagerie.

With the first sullen sign of dawn Tom pushed on ahead, reconnoitered the Upper Spring, found it deserted and went on, riding some hundreds of yards from, but parallel to, the trail and soon came to Cold Spring. Here he saw quantities of camp and riding gear, abandoned firelocks, personal belongings, and other things "forgotten" by the brave Armijo and his army in their precipitate retreat from the Texans, while the latter were still one hundred and fifty miles away. Scouting in the vicinity for awhile he rode back and met the little atejo, which had been plodding steadily on at its pace of three miles an hour; and all the urging of which the men were capable would not increase that speed.

At the Upper Spring, which poured into a ravine and flowed toward the Cimarron a few miles to the north, the wagon road drew farther from the river and ran toward the Canadian; and here the little party left it to turn and twist over and around hills, ravines, pastures and woods, and then slopped down the middle of a storm-swollen rivulet. They turned up one of its small feeders and followed it for half a mile and then, crossing a little divide, struck another small brook and splashed down it until they came to the Cimarron. Here they threw into the river the useless contents of the false packs, distributed the supplies among the mules, and pushed on again upstream along the bank.

They now were well up on the headwaters of the river and its width was negligible, although its storm-fed torrent boiled and seethed and gave to it a false fierceness. Their doubling and the hiding of their trail in the streams had not been done so much for the purpose of throwing the Mexicans off their track, as to make their pursuers think they were trying to throw them off. They knew that the Mexicans, upon losing the tracks, would strike straight for the old and now almost abandoned Indian trail for Bent's Fort.

"We got about a ten-hour start on 'em," growled Tom, "but they'll cut that down quick, once they git goin'. Reckon I'll lay back a-ways an' slow 'em up if they git hyar too soon."

Zeb and Jim wheeled their horses and without a word accompanied him to the rear.

Hank, leading the bell mule, pushed on, looking for the site of his old cache and for a good place to cross the swollen stream, and he soon stopped at the water's edge and howled like a wolf. In a few minutes his companions came up, reported no Mexicans in sight, and unpacked the more perishable supplies. These they carried across to the other bank, their horses swimming strongly and soon the mules were ready to follow. Tom led off, entering the stream with the picket rope of the bell mule fastened to his saddle, and with his weapons, powder horn and "possible" sack high above his head. His horse breasted the current strongly, quartering against it, and the bell mule followed. After her, with a slight show of hesitation, came the others, the three remaining hunters bringing up the rear.

As the atejo formed again and started forward Hank hung back, peering into the stunted trees and brush on the other side of the stream.

"Come on, Hank," said Tom. "What ye lookin' fer? They warn't in sight."

"I war sorta hankerin' fer 'em ter show up," growled Hank with deep regret. "That's plumb center range from hyar, over thar. Wouldn't mind takin' a couple o' cracks at 'em, out hyar by ourselves, us four. Allus hate ter turn my tail ter yaller-bellies like them varmints. I hate 'em next ter Crows!" He slowly turned his horse and fell in behind the last mule, glancing back sorrowfully. Then he looked ahead. "Thar's my ol' cache," he chuckled.

Before them on the right was an eroded hill with steep sides, its flat top covered with a thick mass of brush, berry bushes and scrub timber, and on its right was a swamp, filled with pools and rank with vegetation. The dry wash marking the end of the great buffalo trail was dry no longer, but poured out a roiled, yellow-brown stream into the dirty waters of the Cimarron.

Rounding the hill they stopped and exchanged grins, for in a little horseshoe hollow two horses, with pack saddles on their backs, stopped their grazing, pulled to the end of their picket-ropes, and looked inquiringly at the invaders.

"Thar's jest no understandin' th' ways o' Providence," chuckled Hank as he dismounted. "Hyar we been a-wishin' an' a-wishin' fer a couple o' hosses to take th' place o' these cold-'lasses mules, an' danged if hyar they ain't, saddles an' all, right under our noses."

While he went along the back trail on foot to a point from where he could see the river, his companions became busy. They pooled their supplies and packed them securely on the Providence-provided horses, put the rest on their own animals, picketed the mules and removed the bell from the old mare, tossing it aside so its warning tinkle would be stilled. Signalling Hank, in a few minutes they were on their way again along the faint and in many places totally effaced trail leading over the wastes to the distant trading post on the Arkansas. Coming to a rainwater rivulet Hank sent them westward down its middle while he rode splashingly upstream. Soon coming to a tangle of brush he forced his horse to take a few steps around it on the bank, returned to the stream and then, holding squarely to its middle, picked his way through the tangle and rode back to rejoin his friends, having left behind him a sign of his upward passing. In case Providence went to sleep and took no more interest in his affairs, he had the satisfaction of knowing that he had done what he could to hide their trail.

He found his friends waiting for him and he shook his head as he joined them. "Danged if I like this hyar hidin'," he growled, coming back to his pet grievance. "I most gen'rally 'd ruther do it myself."

"But it ain't a question o' fighting," retorted Tom. "We got ter hide our trail from now on in case some greaser gits away, like they did from them Texans back nigh th' Crossin', an' takes th' news in ter th' settlements that we didn't go ter Bent's after we left th' wagon road. Ye'll git all th' danged fightin' yer lookin' fer afore ye puts Santa Fe behind ye—an' I'm bettin' we'll all show our trails a hull lot worse afore we git through ter Bent's. Come on; Turley's ranch is a long ways off. If yer itchin' ter try that repeatin' rifle ye'll shore git th' chance ter, later."

Hank grinned guiltily and while he was not thoroughly convinced of the soundness of their flight, so far as his outward appearances showed, he grunted a little but pushed on and joined his partner. In a few minutes he grinned again.

"I ain't never had th' chanct ter try fer six plumb-centers without takin' th' rifle from my shoulder," he remarked. "Jest wait till I take this hyar Colt up in th' Crow country!" He chuckled with anticipated pleasures and then glanced sidewise at his partner. "Say, Tom," he said, reminiscently; "who air th' three other best men yer gal was thinkin' of, back thar in that little clearin'?"

"What you mean?" demanded Tom, whirling in his saddle, his face flushing under its tan. "An' she ain't my gal, neither."

Hank chirped and twittered a bit. "Then who's is she?"

"Don't know; but she won't like bein' called mine. Ye oughtn't call her that."

"Not even atween us two?"

"Not never, a-tall."

"That so?" muttered Hank, a vague plan presenting itself to his mind, to be considered and used later. "Huh! I must be gittin' old an' worthless," he mourned. "I been readin' signs fer more'n thirty year, an' I ain't never read none that war airy plainer, arter them thievin' 'Rapahoes turned tail an' lit out. Anyhow, I reckon mebby yer safe if ye keep on thinkin' that she's yer gal." He scratched his chin. "But who war th' other three?"

"Why, I do remember her saying something like that," confessed Tom slowly, tingling as his memory hurled the whole scene before him. "Reckon she meant Uncle Joe an' her father."

"That accounts fer two o' 'em," said Hank, nodding heavily; "but who in tarnation is th' third?"

"Don't know," grunted Tom.

"Huh! Bet he's that stuck-up, no-'count doctor feller. Yeah; that's who it is." He glanced slyly at his frowning friend. "Told ye I war gettin' old an' worthless. Gosh! an' she's goin' all th' rest o' th' way ter Santer Fe with him!" He slapped his horse and growled in mock anxiety. "We better git a-goin' an' not loaf like we air. Santer Fe's a long ways off!"

Two miles further on they turned up a little branch of the stream and Hank, stopping his horse, threw up his hand. "Listen!" he cried.

Four pairs of keen ears sifted the noises of the intermittent wind and three pairs of eyes turned to regard their companion.

"What ye reckon ye heard?" curiously asked Zeb.

"I'd take my oath I heard rifle shots—a little bust o' 'em," replied Hank. "Thar ain't no questionin' it; I am gittin' old. Come along; we'll keep ter th' water fur's we kin, anyhow."

Back at the encampment of the caravan dawn found the animals stampeded, and considerable time elapsed before they were collected and before the absence of Tom and his friends was noticed. Then, with many maledictions, Pedro rallied his friends and set out along the wagon road, following a trail easily seen notwithstanding

Comments (0)