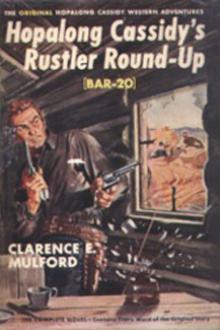

''Bring Me His Ears'' by Clarence E. Mulford (howl and other poems TXT) 📕

"I know how you feel, Mr. Boyd. Have you seen your father since you landed?"

Tom reluctantly shook his head. "It would only reopen the old bitterness and lead to further estrangement. No man shall ever speak to me again as he did--not even him. If you should see him, Jarvis, tell him I asked you to assure him of my affection."

"I shall be glad to do that," replied the clerk. "You missed him by only two days. He asked for you and wished you success, and said your home was open to you when you returned to resume your studies. I think, in his heart, he is proud of you, but too stubborn to admit it." As he spoke he chanced to glance through the window of the store. "Don't look around," he warned. "I want to tell you t

Read free book «''Bring Me His Ears'' by Clarence E. Mulford (howl and other poems TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Clarence E. Mulford

- Performer: -

Read book online «''Bring Me His Ears'' by Clarence E. Mulford (howl and other poems TXT) 📕». Author - Clarence E. Mulford

Jacques returned shortly with Bent's thirsty hirelings, and after some negotiations and the promise of horses for them to ride, the Indians accepted his offer. They showed a little reluctance until he had given each of them a drink of his raw, new whiskey, which seemed to serve as fuel to feed a fire already flaming. The bargain struck, he ordered them fed and let them sleep on the softest bit of ground they could find around the rancho.

CHAPTER XVIIISANTA FE

After an early breakfast the atejo of nineteen mules besides the mulera, or bell mule, was brought out of the pasture and the aparejos, leather bags stuffed with hay, thrown on their backs and cinched fast with wide belts of woven sea-grass, which were drawn so cruelly tight that they seemed almost to cut the animals in two; this cruelty was a necessary one and saved them greater cruelties by holding the packs from slipping and chafing them to the bone. Groaning from the tightness of the cinches they stood trembling while the huge cruppers were put into place and breast straps tightened. Then the carga was placed on them, the whiskey carriers loaded with a cask on each side, firmly bound with rawhide ropes; the meal carriers with nearly one hundred fifty pounds in sacks on each side. While the mules winced now, after they had become warmed up and the hay of the aparejos packed to a better fit, they could travel longer and carry the heavy burdens with greater ease than if the cinches were slacked. The packing down and shaping of the aparejo so loosened the cinch and ropes that frequently it was necessary to stop and tighten them all after a mile or so had been put behind.

The atejo was in charge of a major-domo, five arrieros, or muleteers and a cook, or the madre, who usually went ahead and led the bell mule. All the men rode well-trained horses, and both men and horses from Turley's rancho were sleek, well fed and contented, for the proprietor was known throughout the valley, and beyond, for his kindness, honesty and generosity; and he was repaid in kind, for his employees were faithful, loyal, and courageous in standing up for his rights and in defending his property. Yet the time was to come some years hence when his sterling qualities would be forgotten and he would lose his life at the hands of the inhabitants of the valley.

The atejo swiftly and dexterously packed, the two pairs of bloodthirsty looking Indian guards divided into advance and rear guard, the madre led the bell mule down the slope and up the trail leading over the low mountainous divide toward Ferdinand de Taos, the grunting mules following in orderly file.

The trail wandered around gorges and bowlders and among pine, cedar, and dwarf oaks and through patches of service berries with their small, grapelike fruit, and crossed numerous small rivulets carrying off the water of the rainy season. Taos, as it was improperly called, lay twelve miles distant at the foot of the other side of the divide, and it was reached shortly after noon without a stop on the way. The "noonings" observed by the caravans were not allowed in an atejo, nor were the mules permitted to stop for even a moment while on the way, for if allowed a moment's rest they promptly would lie down, and in attempting to arise under their heavy loads were likely to strain their loins so badly as to render them forever unfit for work. To remove and replace the packs would take too much time. Because of the steady traveling the day's journey rarely exceeded five or six hours nor covered more than twelve to fifteen miles.

Taos reached, the packs were removed and covered by the aparejos, each pile kept separate. Turned out to graze with the bell mule, without picket rope or hobbles, the animals would not leave her and could be counted on, under ordinary circumstances, to be found near camp and all together.

Taos, a miserable village of adobes, and the largest town in the valley, had a population of a few American and Canadian trappers who had married Mexican or Indian women; poor and ignorant Mexicans of all grades except that of pure Spanish blood, and Indians of all grades except, perhaps, those of pure Indian blood. The mixed breed Indians had the more courage of the two, having descended from the Taosas, a tribe still inhabiting the near-by pueblo, whose warlike tendencies were almost entirely displayed in defensive warfare in the holding of their enormous, pyramidal, twin pueblos located on both sides of a clear little stream. In the earlier days marauding bands of Yutaws and an occasional war-party of Cheyennes or Arapahoes had learned at a terrible cost that the Pueblo de Taos was a nut far beyond their cracking, and from these expeditions into the rich and fertile valley but few returned.

Here was a good chance to test the worth of their disguises, for the three older plainsmen were well-known to some of the Americans and Canadians in the village, having been on long trips into the mountains with a few of them. And so, after the meal of frijoles, atole and jerked meat, the latter a great luxury to Mexicans of the grade of arrieros, Hank and his two Arapahoe companions left the little encampment and wandered curiously about the streets, to the edification of uneasy townsfolk, whose conjectures leaned toward the unpleasant. Ceran St. Vrain, on a visit to the town, passed them close by but did not recognize the men he had seen for days at a time at his trading post on the South Platte. Simonds, a hunter from Bent's Fort, passed within a foot of Hank and did not know him; yet the two had spent a season together in the Middle Park, lying just across the mountain range west of Long's Peak.

Continuing on their way the next morning they camped in the open valley for the night, and the next day crossed a range of mountains. The next village was El Embudo, a miserable collection of mud huts at the end of a wretched trail. The Pueblo de San Juan and the squalid, poverty-stricken village of La Canada followed in turn. Everywhere they found hatred and ill-disguised fear of the Texans roaming beyond the Canadian. Next they reached the Pueblo de Ohuqui and here found snug accommodations for themselves and their animals in the little valley. From the pueblo the trail lay through an arroyo over another mountain and they camped part way down its southeast face with Santa Fe sprawled out below them.

Morning found them going down the sloping trail, the Indian escort surreptitiously examining their rifles, and in the evening they entered the collection of mud houses honored by the name of San Francisco de la Santa Fe, whose population of about three thousand souls was reputed to be the poorest in worldly wealth in the entire province of New Mexico; and, judging from the numbers of openly run gambling houses, rum shops and worse, the town might have deserved the reputation of being the poorest in morals and spiritual wealth.

Sprawled out under the side of the mountain, its mud houses of a single story, its barracks, calabozo and even the "palace" of the governor made of mud, with scarcely a pane of glass in the whole town; its narrow streets littered with garbage and rubbish; with more than two-thirds of its population barefooted and unkempt, a mixture of Spaniards and Indians for generations, in which blending the baser parts of their natures seemed singularly fitted to survive; with cringing, starving dogs everywhere; full of beggars, filthy and in most cases disgustingly diseased, with hands outstretched for alms, as ready to curse the tight of purse as to bless the generous, and both to no avail; with its domineering soldiery without a pair of shoes between them, its arrogant officers in shiny, nondescript uniforms and tarnished gilt, with huge swords and massive spurs, to lead the unshod mob of privates into cowardly retreat or leave them to be slaughtered by their Indian foes, whose lances and bows were superior in accuracy and execution to the ancient firelocks so often lacking in necessary parts; reputed to be founded on the ruins of a pueblo which had flourished centuries before the later "city" and no doubt was its superior in everything but shameless immorality. There, under Sante Fe mountain and the pure and almost cloudless blue sky, along the little mountain stream of the same name, lay Santa Fe, the capital of the department of New Mexico, and the home of her vainglorious, pompous, good-looking, and brutal governor; Santa Fe, the greatest glass jewel in a crown of tin; Santa Fe, the customs gate and the disappointing end of a long, hard trail.

Through the even more filthy streets of the poverty-stricken outskirts of the town went the little atejo, disputing right-of-way in the narrow, porch-crowded thoroughfares with hoja (corn husk) sellers and huge burro loads of pine and cedar faggots gathered from the near-by mountain; past the square where the mud hovels of the soldiers lay; past a mud church whose tall spire seemed ever to be stretching away from the smells below; past odorous hog stys, crude mule corrals with their scarred and mutilated creatures, and sheep pens, and groups of avid cock-fighters; past open doors through which the halfbreed women, clothed in a simple garment hanging from the shoulders, could be seen cooking frijoles or the thin, watery atole and hovering around the flat stones which served for stoves; past these and worse plodded the atejo, the shrewd mules braying their delight at a hard journey almost ended. Sullen Indians, apologetic Mexicans, swaggering and too often drunken soldiers gave way to them, while a string of disputing, tail-tucking dogs followed at a distance, ever wary, ever ready to wheel and run.

Reaching the Plaza Publica, which was so bare of even a blade of grass or a solitary tree, and its ground so scored and beaten and covered with rubbish to suggest that it suffered the last stages of some earthly mange, they came to the real business section of the town, where nearly every shop was owned by foreigners. Around this public plaza stood the architectural triumphs of the city. There was the palacio of the governor, with its mud walls and its extended roof supported on rough pine columns to form a great porch; the custom-house, with its greedy, grafting officials; the mud barracks connected to the atrocious and much dreaded calabozo, whose inmates had abandoned hope as they crossed its threshold; the mud city hall, the military chapel, fast falling into ruin, and a few dwellings. The interest attending the passing of the atejo increased a little as the pack train crossed this square, for the Indian guards were conspicuous by their height and by the breadth of shoulder, and the excellence of their well-kept weapons. Strangers were drawing more critical attention these days, with the Texan threat hanging over the settlements along the Pecos and the Rio Grande. Peon women and Indian squaws regarded the four with apparent approval and as they left the square and plunged into the poorer section again, compliments and invitations reached their ears. Hopeless mozos, or ill-paid servants, most of them kept in actual slavery by debts they never could pay off because of the system of accounting used against them, regarded the four enviously and yearned for their freedom.

Of the four

Comments (0)