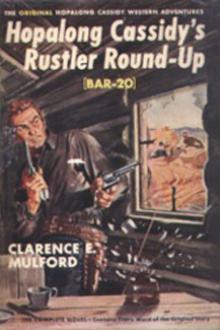

''Bring Me His Ears'' by Clarence E. Mulford (howl and other poems TXT) 📕

"I know how you feel, Mr. Boyd. Have you seen your father since you landed?"

Tom reluctantly shook his head. "It would only reopen the old bitterness and lead to further estrangement. No man shall ever speak to me again as he did--not even him. If you should see him, Jarvis, tell him I asked you to assure him of my affection."

"I shall be glad to do that," replied the clerk. "You missed him by only two days. He asked for you and wished you success, and said your home was open to you when you returned to resume your studies. I think, in his heart, he is proud of you, but too stubborn to admit it." As he spoke he chanced to glance through the window of the store. "Don't look around," he warned. "I want to tell you t

Read free book «''Bring Me His Ears'' by Clarence E. Mulford (howl and other poems TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Clarence E. Mulford

- Performer: -

Read book online «''Bring Me His Ears'' by Clarence E. Mulford (howl and other poems TXT) 📕». Author - Clarence E. Mulford

When they awakened the next morning they recognized two old friends from Bent's Fort, a trader from St. Vrain's, and an American hunter and trapper from the Pueblo near the junction of the Arkansas and Boiling Spring Rivers. The simple breakfast was soon dispatched and gossip and news exchanged, and then Hank led aside a hunter named Hatcher, who stood high at Bent's Fort, and earnestly conversed with him. In a few moments Hank turned, looked reassuringly at Tom and smiled. Bent's little ranch on the Purgatoire was being worked and improved and there would be men and a relay of horses there, providing that the Utes overlooked the valley in the meantime.

All that day they remained indoors and when night came they slipped out, one by one, and drifted back to the corral where the atejo still remained. They had lost their rifles, were sullen and taciturn from too much drink, and paid no attention to the knowing grins of the friendly muleteers. Thenceforth they drew only glances of passing interest on the streets, no one giving a second thought to the stolid, dulled and sodden wrecks in their filthy, nondescript apparel; and the guard at the palacio gave them cigarettes rolled in corn husks for running errands, and found amusement in playing harmless tricks on them.

At the barracks they were less welcome, Don Jesu and Robideau, both subordinates of Salezar, scarcely tolerating them; while Salezar, himself, kicked them from in front of the door and threatened to cut off their ears if he caught them hanging around the building. They accepted the kicks as a matter of course and thenceforth shrunk from his approach; and he sneered as he thought of their degradation from once proud and vengeful warriors of free and warlike tribes, to fawning beggars with no backbone. But even he, when the need arose, made use of them to fetch and carry for him and to do menial tasks about the mud house he called his home. He had seen many of their kind and wasted no thought on them.

He was the same cruel and brutal tyrant who had herded almost two hundred half-starved and nearly exhausted men over that terrible trail down the valley of the Rio Grande, and his soldiers stood in mortal terror of him and meekly accepted treatment that in any other race would have swiftly resulted in his death. He had played a prominent part in the capture and herding of the Texan prisoners and loved to boast of it at every opportunity, using some of the incidents as threats to his unfortunate soldiers. Tom and his friends witnessed scenes that made their blood boil more than it boiled over the indignities they elected to suffer, and sometimes it was all they could do to refrain from killing him in his tracks. At the barracks he was a roaring lion, but at the palacio, in the sight and hearing of the chief jackal, he reminded them of a whipped cur.

CHAPTER XXTOM RENEGES

As the days passed while waiting for the return of the caravan to Missouri, Patience rode abroad with either her uncle or her father, sometimes in the Dearborn, but more often in the saddle. She explored the ruins of the old church at Pecos, where the Texan prisoners had spent a miserable night; the squalid hamlets of San Miguel, which she had passed through on her way to Santa Fe, and Anton Chico had been visited; the miserable little sheep ranchos had been investigated and other rides had taken her to other outlying districts; but the one she loved best was the trail up over the mountain behind Santa Fe. The almost hidden pack mules and their towering loads of faggots, hoja, hay and other commodities were sights she never tired of, although the scars on some of the meek beasts once in awhile brought tears to her eyes. The muleteers, beneficiaries of her generosity, smiled when they saw her and touched their forelocks in friendly salutation.

On the mountain there was one spot of which she was especially fond. It was a little gully-like depression more than halfway up that seemed to be much greener than the rest of the mountain side, and always moist. The trees were taller and more heavily leafed And threw a shade which, with the coolness of the moist little nook, was most pleasant. It lay not far from the rutted, rough and busy trail over the mountain, which turned and passed below it, the atejos and occasional picturesque caballeros on their caparisoned horses, passing in review before her and close enough to be distinctly seen, yet far enough away to hide disillusioning details. The mud houses of the town at the foot of the long slope, with their flat roofs, looked much better at this distance and awakened trains of thought which nearness would have forbidden. It was also an ideal place to eat a lunch and she and Uncle Joe or her father made it their turning point.

Her daily rides had given her confidence, and the stares which first had followed her soon changed to glances of idle curiosity. Of Armijo she neither had seen nor heard anything more and scarcely gave him a thought, and the Mexican officers she met saluted politely or ignored her altogether. Her uncle still harped about Santa Fe being no place for her, but, having the assurance that she would return to St. Louis with the caravan, was too wise to press the matter. His efforts were more strongly bent to get his brother to sell out and he had sounded Woodson to see if that trader would take over the merchandise. Adam Cooper seemed to consider closing out his business and returning to Missouri, but he would not sacrifice it, and there the matter hung, swaying first to one side and then to the other. By this time Santa Fe had palled on the American merchant and he had laid by sufficient capital to start in business in St. Louis or one of the frontier towns, and his brother was confident that if the stock could be disposed of for a reasonable sum that Adam would join the returning caravan.

It was in the storehouse of Webb and Birdsall one night, about a week before the wagons were being put in shape for the return trip that the matter was settled. Disturbing rumors were floating up from the south about a possible closing of the ports of entry of the Department of New Mexico, due to the dangers to Mexican traders on the long trail because of the presence of Texan raiding parties. The Texans had embittered the feelings of the Mexicans against the Americans, whom they knew to be universally in favor of the Lone Star Republic, and the Texan raids of this summer were taken as a forecast of greater and more determined raids for the following year.

When Adam and Joe Cooper joined the little group in the warehouse on this night, they met two Missourians who had just returned from Chihuahua with a train of eleven wagons. These traders, finding business so good in the far southern market, and having made arrangements with some Englishmen there, who were high in favor with the Federal authorities, were anxious to make another trip if they could load their wagons at a price that would make the journey worth while. They were certain that the next year would find the Mexican ports closed against the overland traffic, eager to clean up what they could before winter set in and to sell their outfits and return by water. They further declared that a tenseness was developing between the Federal government and the United States, carefully hidden at the present, which would make war between the two countries a matter of a short time. Texas was full of people who were urging annexation to the United States, and their numbers were rapidly growing; and when the Lone Star republic became a state in the American federation, war would inevitably follow. Some in the circle dissented wholly or in part, but all admitted that daily Mexico was growing more hostile to Americans.

"Wall, we ain't forcin' our opinions on nobody," said one of the Chihuahua traders. "We believe 'em ourselves, an' we want ter make another trip south. Adam, we've heard ye ain't settled in yer mind about stayin' through another winter hyar. We'll give ye a chanct ter clear out; what ye got in goods, an' what ye want fer'em lock, stock an' bar'l?"

"What they cost us here in Santa Fe," said Uncle Joe quickly, determined to force the issue. "We just brought in more'n two wagon loads, an' what we had on hand will go a long way toward helpin' you fill your wagons. Come around tomorrow, look th' goods over, an' if they suit you, we'll add twelve cents a pound for th' freight charge across th' prairies an' close 'em out to you. Ain't that right, Adam?" he demanded so sharply and truculently that his brother almost surrendered at once. Seeing that they had an ally in Uncle Joe the traders pushed the matter and after a long, haggling discussion, they offered an additional five per cent of the purchase price for a quick decision.

Uncle Joe accepted it on the spot and nudged his brother, who grudgingly accepted the terms if the traders would buy the two great wagons and their teams. This they promised to do if they could find enough extra goods to fill them, and they soon left the warehouse for fear of showing their elation. They knew where they could sell the wagons at a profit with a little manipulation on the part of their English friend.

Elated by the outcome of his protracted arguments, Uncle Joe hurried around to Armstrong's store and told the news to Tom and his three friends.

"We can get them goods off our hands in two days," he exulted; "an' th' caravan will be ready to leave inside a week. Don't say a word to nobody, boys. We'll try to sneak Adam and Patience out of town so Armijo won't miss 'em till they're on th' trail. Them Chihuahua traders won't disturb th' goods before we start for home because they got to get a lot more to fill their wagons, an' th' merchandise is safer in th' store than it will be under canvas. I wish th' next week was past!"

To wish the transaction kept a secret and to keep it a secret were two different things. The Chihuahua traders found more merchants who felt that they would be much safer in Missouri than in Santa Fe, and the south-bound wagon train was stocked three days before time for the Missouri caravan to leave. There were certain customs regulations relating to goods going through to El Paso and beyond, certain involved and exacting forms to be obtained and filled out, much red tape to be cut with golden shears and many palms to be crossed with specie. Uncle Joe and his brother found that the matter of transferring their goods to the traders took longer than they expected and were busy in the store for several days, leaving Patience to make the most of the short time remaining of her stay in the capital of the Department of New Mexico.

At last came the day when the eastbound caravan was all

Comments (0)