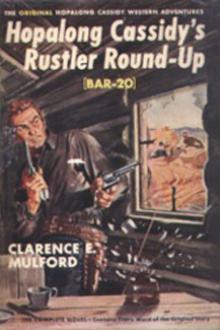

''Bring Me His Ears'' by Clarence E. Mulford (howl and other poems TXT) 📕

"I know how you feel, Mr. Boyd. Have you seen your father since you landed?"

Tom reluctantly shook his head. "It would only reopen the old bitterness and lead to further estrangement. No man shall ever speak to me again as he did--not even him. If you should see him, Jarvis, tell him I asked you to assure him of my affection."

"I shall be glad to do that," replied the clerk. "You missed him by only two days. He asked for you and wished you success, and said your home was open to you when you returned to resume your studies. I think, in his heart, he is proud of you, but too stubborn to admit it." As he spoke he chanced to glance through the window of the store. "Don't look around," he warned. "I want to tell you t

Read free book «''Bring Me His Ears'' by Clarence E. Mulford (howl and other poems TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Clarence E. Mulford

- Performer: -

Read book online «''Bring Me His Ears'' by Clarence E. Mulford (howl and other poems TXT) 📕». Author - Clarence E. Mulford

Don Jesu swaggered along the side of the building, caught sight of the disreputable Delaware and contemptuously waved him away. "Out of my sight, you drunken beggar and son of a beggar! If I catch you here once more I'll hang you by your thumbs! Vamoose!"

The Delaware stiffened a little and seemed reluctant to obey the command. "I seek my friends," he replied in a guttural polyglot. "I do no harm."

Don Jesu's face flamed and he drew his sword and brought the flat of the blade smartly across the Indian's shoulder. "But once more I tell you to vamoose! Pronto!" He drew back swiftly and threw the weapon into position for a thrust, for he had seen a look flare up in the Indian's eyes that warned him.

The Delaware cringed, muttered something and slunk back along the wall and as he reached the corner of the building he bumped solidly into Robideau, who at that moment turned it. The foot of the second officer could not travel far enough to deliver the full weight of the kick, but the impact was enough to send the Indian sprawling. As he clawed to hands and knees, Robideau stood over him, sword in hand, threats and curses pouring from him in a burning stream. The Indian paused a moment, got control over his rage, ran off a short distance on hands and knees and, leaping to his feet, dashed around the corner of the building to the hilarious and exultant jeers of the sycophantic soldiers. He barely escaped bumping into a huge, screeching and ungainly carreta being driven by a soldier and escorted by a squad of his fellows under the personal command of Salezar. The lash of a whip fell across his shoulders and cut through blanket and shirt. The second blow was short and before another could be aimed at him, the Delaware had darted into a passage-way between two buildings.

The officer laughed loudly, nodded at the scowling driver and again felt of the canvas cover of the cart: "The city is full of vermin," he chuckled. "There's not much difference between Texans and Americans, and these sotted Indians. Tomorrow we will be well rid of many of the gringo dogs and we will attend to these strange Indians when this present business has been taken care of. But there is one gringo who will remain with us!" He laughed until he shook. "Captain Salezar today; Colonel, tomorrow; quien sabe?"

He looked at two of his soldiers, squat, powerful half-breeds, and laughed again. "Jose is a strong man. Manuel is a strong man. Perhaps tomorrow we will give each one of them two Indians and see which can flog the longest and the hardest; but," he warned, his face growing hard and cruel, "the man who bungles his work today will have no ears tomorrow!"

The Delaware, his right hand thrust into his shirt under the dirty blanket, crouched in the doorway and was making the fight of his life against the murderous rage surging through him. The words of the officer reached him well enough, but in his fury were unintelligible. Wild, mad plans for revenge were crowding through his mind, mixed and jumbled until they were nothing more than a mental kaleidoscope, and constantly thrown back by the frantic struggles of reason. He had nursed the thought of revenge, mile after mile, day after day, across the prairies and the desert; but for the last half month he had fought it back for the safety his freedom might give to the woman he loved.

The grotesque, ungainly cart rumbled and bumped, clacked and screeched down the street, farther and farther away and still he crouched in the doorway. The sounds died out, but still he remained in the sheltering niche. Finally his hand emerged from under the blanket and fell to his side, and a wretched Indian slouched down the street toward the Plaza Publica. In command of himself once more he shuffled over to the guard house in the palacio and leaned against the wall, the welt on his back burning him to the soul, as Armijo's herald stepped from the main door, blew his trumpet and announced the coming of the governor. Pedestrians stopped short and bowed as the swarthy tyrant stalked out to his horse, mounted and rode away, his small body-guard clattering after him. The Delaware, to hide the expression on his face, bowed lower and longer than anyone and then slyly produced a plug of smuggled Kentucky tobacco and slipped it to the sergeant of the guard.

"They'll catch you yet, you thief of the North," warned the sergeant, shaking a finger at the stolid Indian. "And when they do you'll hang by the thumbs, or lose your ears." He grinned and shoved the plug into his pocket, not seeming to be frightened by becoming an accessory after the fact. "Our governor is in high spirits today, and our captain's face is like the mid-day sun. He is a devil with the women, is Armijo and his señora doesn't care a snap. Lucky man, the governor." He laughed and then looked curiously at his silent companion. "Where do you come from, and where do you go?"

The Delaware waved lazily toward the North. "Señor Bent. I return soon."

"Look to it that you do, or the calabozo will swallow you up in one mouthful. I hear much about the palacio." He shook his finger and his head, both earnestly.

The Delaware drew back slightly and glanced around. Drawing his blanket about him he turned and slouched away, leaving the plaza by the first street, and made his slinking and apologetic way to Armstrong's, there to wait until dark. His three friends were there already and were rubbing their pistols and rifles, elated that the morrow would find them on the trail again. The two Arapahoes planned to accompany the caravan as far as the Crossing of the Arkansas and there turn back toward Bent's Fort, following the northern branch of the trail along the north bank of the river.

"Better jine us, Tom," urged Jim Ogden. "You an' Hank an' us will stay at th' fort till frost comes, an' then outfit thar an' spend th' winter up in Middle Park."

"Or we kin work up 'long Green River an' winter in Hank's old place," suggested Zeb Houghton, rubbing his hands. "Thar'll be good company in Brown's Hole; an' mebby a scrimmage with th' thievin' Crows if we go up that way. Yer nose will be outer jint in th' Missouri settlements. I know a couple o' beaver streams that ain't been teched yit." He glanced shrewdly at the young man. "It's good otter an' mink country, too. We'll build a good home camp an' put up some lean-tos at th' fur end o' th' furtherest trap lines. Th' slopes o' th' little divides air thick with timber fer our marten traps, an' th' tops air bare. Fox sets up thar will git plenty o' pelts. I passed through it two year ago an' can't hardly wait ter git back ag'in. It's big enough fer th' hull four o' us."

"Thar's no money in beaver at a dollar a plew," commented Hank, watching his partner out of the corner of his eye. "Time war when it war worth somethin', I tell ye; but them days air past—an' th' beaver, too, purty nigh. I remember one spring when I got five dollars a pound fer beaver from ol' Whiskey Larkin. Met him on th' headwaters o' th' Platte. He paid me that then an' thar, an' then had ter pack it all th' way ter Independence. But it's different with th' other skins, an' us four shore could have a fine winter together."

"It's allus excitin' ter me ter wait till th' pelts prime, settin' in a good camp with th' traps strung out, smokin' good terbaker an' eatin' good grub," said Ogden, reminiscently. "Then th' frosts set in, snow falls an' th' cold comes ter stay; an' we web it along th' lines settin' traps fer th' winter's work. By gosh! What ye say, Tom?"

Tom was studying the floor, vainly trying to find a way to please his friends and to follow the commands of an urging he could not resist. For him the mating call had come, and his whole nature responded to it with a power which would not be denied. On one hand called the old life, the old friends to whom he owed so much; a winter season with them in a good fur country, with perfect companionship and the work he loved so dearly; on the other the low, sweet voice of love, calling him to the One Woman and to trails untrod. The past was dead, living only in memory; the future stirred with life and was rich in promise. He sighed, slowly shook his head and looked up with moist eyes, glancing from one eager face to another.

"I'm goin' back ter Missoury," he said in a low voice. "Thar's a question I got ter ask, back thar, when th' danger's all behind an' it kin be asked fair. If th' answer is 'no' I promise ter jine ye at Bent's or foller after. Leave word fer me if ye go afore I git thar. But trappin' is on its last legs, an' th' money's slippin' out o' it, like fur from a pelt in th' spring; 'though I won't care a dang about that if I has ter turn my back on th' settlements." His eyes narrowed and his face grew hard. "Jest now I'm worryin' about somethin' else. Here I am in Santer Fe, passin' Armijo an' Salezar every day, an' have ter turn my back on one of th' big reasons fer comin' hyar. Thar's a new welt acrost my back that burns through th' flesh inter my soul like a livin' fire. Thar's an oath I swore on th' memory of a close friend who war beaten an' starved an' murdered; an' now I'm a lyin' dog, an' my spirit's turned ter water!" He leaped up and paced back and forth across the little room like a caged panther.

Hank cleared his throat, his painted face terrible to look upon. "Hell!" he growled, squirming on his box. "Them as know ye, Tom Boyd, know ye ain't neither dog ner liar! Takes a good man ter stand what ye have, day arter day, feelin' like you do, an' keep from chokin' th' life outer him. We've all took his insults, swallered 'em whole without no salt; ye wouldn't say all o' us war dogs an' liars, would ye? Tell ye what; we've been purty clost, you an' me—suppose I slip back from th' Canadian an' git his

Comments (0)