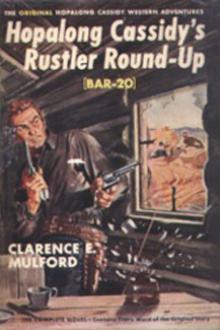

''Bring Me His Ears'' by Clarence E. Mulford (howl and other poems TXT) 📕

"I know how you feel, Mr. Boyd. Have you seen your father since you landed?"

Tom reluctantly shook his head. "It would only reopen the old bitterness and lead to further estrangement. No man shall ever speak to me again as he did--not even him. If you should see him, Jarvis, tell him I asked you to assure him of my affection."

"I shall be glad to do that," replied the clerk. "You missed him by only two days. He asked for you and wished you success, and said your home was open to you when you returned to resume your studies. I think, in his heart, he is proud of you, but too stubborn to admit it." As he spoke he chanced to glance through the window of the store. "Don't look around," he warned. "I want to tell you t

Read free book «''Bring Me His Ears'' by Clarence E. Mulford (howl and other poems TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Clarence E. Mulford

- Performer: -

Read book online «''Bring Me His Ears'' by Clarence E. Mulford (howl and other poems TXT) 📕». Author - Clarence E. Mulford

"Great Eagle's friends found three brave Pawnees in front of their thunder guns and they feared our young men would fire the great medicine rifles and hurt the Pawnees. We sent out and brought White Bear and his warriors to our camp and treated them as welcome guests. Each of them shall have a horse and a musket, with powder and ball, that they will not misunderstand our roughness."

At that moment yells broke out on all sides of the encampment and warriors were seen dashing west along the trail. A well-armed caravan of twenty-two wagons crawled toward the creek, and Woodson secretly exulted. It was the annual fur caravan from Bent's Fort to the Missouri settlements and every member of it was an experienced man.

The fur train did not seem to be greatly excited by the charging horde, for it only interposed a line of mounted men between the wagons and the savages. The two leaders wheeled and rode slowly off to meet the Indians and soon a second parley was taking place. After a little time the fur caravan, which had moved steadily ahead, reached the encampment and swiftly formed on one side of it. With the coming of this re-enforcement of picked men all danger of war ceased.

Before noon the Pawnee chiefs and some of the elder warriors had paid their visit, received their presents, sold a few horses to wagoners who had jaded animals and then returned to their camp, pitched along the banks of the creek a short distance away. The afternoon was spent in visiting between the two encampments and the night in alert vigilance. At dawn the animals were turned out to graze under a strong guard and before noon the caravan was on its way again, its rear guard and flankers doubled in strength.

Shortly after leaving Ash Creek they came to great sections of the prairie where the buffalo grass was cropped as short as though a herd of sheep had crossed it. It marked the grazing ground of the more compact buffalo herds. The next creek was Pawnee Fork, but since it lay only six miles from the last stopping place, and because it was wise to put a greater distance between them and the Pawnees, the caravan crossed it close to where it emptied into the Arkansas, the trail circling at the double bend of the creek and crossing it twice. Great care was needed to keep the wagons from upsetting here, but it was put behind without accident and the night was spent on the open prairie not far from Little Coon Creek.

The fuel question was now solved and while the buffalo chips, plentiful all around them, made execrable, smudgy fires in wet weather if they would burn at all, in dry weather they gave a quick, hot fire excellent to cook on and one which threw out more heat, with equal amounts of fuel, than one of wood; and after an amusing activity in collecting the chips the entire camp was soon girdled by glowing fires.

The next day saw them nooning at the last named creek, and before nightfall they had crossed Big Coon Creek. For the last score of miles they had found such numbers of rattlesnakes that the reptiles became a nuisance; but notwithstanding this they camped here for the night, which was made more or less exciting because several snakes sought warmth in the blankets of some of the travelers. It is not a pleasant feeling to wake up and find a three-foot prairie rattlesnake coiled up against one's stomach. Fortunately there were no casualties among the travelers but, needless to say, there was very little sleep.

Next came the lower crossing of the Arkansas, where there was some wrangling about the choice of fords; many, fearing the seasonal rise of the river, which they thought was due almost any minute, urged that it be crossed here, despite the scarcity of water, and the heavy pulling among the sand-hills on the other side.

Woodson and the more experienced traders and hunters preferred to chance the rise, even at the cost of a few days' delay, and to cross at the upper ford. This would give them better roads, plenty of water and grass, a safer ford and a shorter drive across the desert-like plain between the Arkansas and the Cimarron. Eventually he had his way and after spending the night at the older ford the caravan went on again along the north bank of the river, and reached The Caches in time to camp near them. The grass-covered pits were a curiosity and the story of how Baird and Chambers had been forced to dig them to cache their goods twenty years before, found many interested listeners.

All this day a heavy rain had poured down, letting up only for a few minutes in the late afternoon, and again falling all night with increased volume. With it came one of those prairie windstorms which have made the weather of the plains famous. Tents and wagon covers were whipped into fringes, several of them being torn loose and blown away; two lightly loaded wagons were overturned, and altogether the night was the most miserable of any experienced so far. While the inexperienced grumbled and swore, Woodson was pleased, for in spite of the delayed crossing of the river, he knew that the dreaded Dry Route beyond Cimarron Crossing would be a pleasant stretch in comparison to what it usually was.

Morning found a dispirited camp, and no effort was made to get under way until it was too late to cover the twenty miles to the Cimarron Crossing that day, and rather than camp without water it was decided to lose a day here. It would be necessary to wait for the river to fall again before they would dare to attempt the crossing and the time might as well be spent here as farther on. The rain fell again that night and all the following day, but the wind was moderate. The river was being watched closely and it was found that it had risen four feet since they reached The Caches; but this was nothing unusual, for, like most prairie streams, the Arkansas rose quickly until its low banks were overflowed, when the loss of volume by the flooding of so much country checked it appreciably; and its fall, once the rains ceased, would be as rapid. High water was not the only consideration in regard to the fording of the river, for the soft bottom, disturbed by the strong current, soon lost what little firmness it had along this part of the great bend, and became treacherous with quicksand. That it was not true quicksand made but little difference so long as it mired teams and wagons.

Another argument now was begun. There were several fords of the Arkansas between this point and the mountains; and there were two routes from here on, the shorter way across the dry plain of the Cimarron, as direct as any unsurveyed trail could be, and the longer, more roundabout way leading another hundred miles farther up the river and crossing it not far from Bent's Fort, over a pebbly and splendid ford. From here it turned south along the divide between Apishara Creek and the Purgatoire River, climbed over the mountain range through Raton Pass, and joined the more direct trail near Santa Clara Spring under the shadow of the Wagon Mound. Beside the ford above Bent's Fort there was another, about thirty miles above The Caches, which crossed the river near Chouteau's Island.

Each ford and each way had its adherents, but after great argument and wrangling the Dry Route was decided upon, its friends not only proving the wisdom of taking the shorter route, but also claimed that the unpleasantness of the miles of dry traveling was no worse than the rough and perilous road over Raton Pass, where almost any kind of an accident could happen to a wagon and where, if the caravan were attacked by Utes or Apaches before it reached the mountain pasture near the top, they would be caught in a strung-out condition and corralling would be impossible. The danger from a possible ambush and from rocks rolled down from above, in themselves, were worse than the desert stretch of the shorter route.

At last dawn broke with a clear sky, and with praiseworthy speed the routine of the camp was rushed and the wagons were heading westward again. Late that afternoon the four divisions became two and rolled down the slope toward the Cimarron Crossing, going into camp within a short distance of the rushing river. The sun had shone all day and the night promised to be clear, and some of the traders whose goods had been wetted by the storm at The Caches when their wagon covers had been damaged or blown away, took quick advantage of the good weather to spread their merchandise over several acres of sand and stubby brush to dry out thoroughly; and the four days spent here, waiting for the river to fall, accomplished the work satisfactorily, although at times the sky was overcast and threatened rain, while the nights were damp.

Some of the more impetuous travelers urged that time would be saved if bullboats were made by stretching buffalo hides over the wagon boxes and floating them across. This had been done more than once, but with only a day or so to wait, and no pressing need for speed, the time saved would not be worth the hard work and the risk of such ferrying. At last the repeated soundings of the bottom began to look favorable and word was passed around that the crossing would take place as soon as the camp was ready to be left the next morning, providing that no rain fell during the night.

Daylight showed a bright sky and a little lower level of the river and it was not long before the first wagon drawn by four full teams, after a warming-up drive, rumbled down the bank and hit the water with a splash. The bottom was still too soft to take things easy in crossing and the teams were not allowed to pause after once they had entered the water. A moment's stop might mire both teams and wagons and cause no end of trouble, hard work, and delay. All day long the wagons crossed and at night they were safely corralled on the farther bank, on the edge of the Dry Route and no longer on United States soil.

That evening the leaders of the divisions went among their followers and urged that in the morning every water cask and container available for holding water be filled. This flat, monotonous, dry plain might require three days to cross and every drop of water would be precious. Should any be found after the recent rains it would be in buffalo wallows and more fit for animals than for human beings. Again in the morning the warning was carried to every person in the camp and the need for heeding it gravely emphasized; and when the caravan started on the laborious and treacherous journey across the fringe of sand-hills and hillocks which extended for five or six miles beyond the river, where upsetting of wagons was by no means an exception, half a dozen wagons had empty water casks. Their owners had been too busy doing inconsequential things to think of obeying the orders for a "water scrape," given for their own good.

The outlying hilly fringe of sand was not as bad as had been expected for the heavy rains had wetted it well and packed the sand somewhat;

Comments (0)