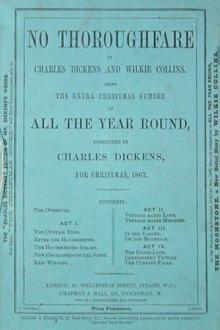

No Thoroughfare by Wilkie Collins (ereader with dictionary .TXT) 📕

"Sally! Hear me, my dear. My entreaty is for no help in the future. It applies to what is past. It is only to be told in two words."

"There! This is worse and worse," cries Sally, "supposing that I understand what two words you mean."

"You do understand. What are the names they have given my poor baby? I ask no more than that. I have read of the customs of the place. He has been christened in the chapel, and registered by some surname in the book. He was received last Monday evening. What have they called him?"

Down upon her knees in the foul mud of the by-way into which they have strayed--an empty street without a thoroughfare giving on the dark gardens of the Hospital--the lady would drop in her passionate entreaty, but that Sally prevents her.

"Don't! Don't! You make me feel as if I was setting myself up to be good. Let me look in your pretty face again. Put yo

Read free book «No Thoroughfare by Wilkie Collins (ereader with dictionary .TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Wilkie Collins

- Performer: -

Read book online «No Thoroughfare by Wilkie Collins (ereader with dictionary .TXT) 📕». Author - Wilkie Collins

“Who are those?” asked Vendale.

“They are our carriers—Defresnier and Company’s,” replied Obenreizer. “Those are our casks of wine.” He was singing to himself, and lighting a cigar.

“I have been drearily dull company to-day,” said Vendale. “I don’t know what has been the matter with me.”

“You had no sleep last night; and a kind of brain-congestion frequently comes, at first, of such cold,” said Obenreizer. “I have seen it often. After all, we shall have our journey for nothing, it seems.”

“How for nothing?”

“The House is at Milan. You know, we are a Wine House at Neuchatel, and a Silk House at Milan? Well, Silk happening to press of a sudden, more than Wine, Defresnier was summoned to Milan. Rolland, the other partner, has been taken ill since his departure, and the doctors will allow him to see no one. A letter awaits you at Neuchatel to tell you so. I have it from our chief carrier whom you saw me talking with. He was surprised to see me, and said he had that word for you if he met you. What do you do? Go back?”

“Go on,” said Vendale.

“On?”

“On? Yes. Across the Alps, and down to Milan.”

Obenreizer stopped in his smoking to look at Vendale, and then smoked heavily, looked up the road, looked down the road, looked down at the stones in the road at his feet.

“I have a very serious matter in charge,” said Vendale; “more of these missing forms may be turned to as bad account, or worse: I am urged to lose no time in helping the House to take the thief; and nothing shall turn me back.”

“No?” cried Obenreizer, taking out his cigar to smile, and giving his hand to his fellow-traveller. “Then nothing shall turn ME back. Ho, driver! Despatch. Quick there! Let us push on!”

They travelled through the night. There had been snow, and there was a partial thaw, and they mostly travelled at a foot-pace, and always with many stoppages to breathe the splashed and floundering horses. After an hour’s broad daylight, they drew rein at the inn-door at Neuchatel, having been some eight-and-twenty hours in conquering some eighty English miles.

When they had hurriedly refreshed and changed, they went together to the house of business of Defresnier and Company. There they found the letter which the wine-carrier had described, enclosing the tests and comparisons of handwriting essential to the discovery of the Forger. Vendale’s determination to press forward, without resting, being already taken, the only question to delay them was by what Pass could they cross the Alps? Respecting the state of the two Passes of the St. Gotthard and the Simplon, the guides and mule-drivers differed greatly; and both passes were still far enough off, to prevent the travellers from having the benefit of any recent experience of either. Besides which, they well knew that a fall of snow might altogether change the described conditions in a single hour, even if they were correctly stated. But, on the whole, the Simplon appearing to be the hopefuller route, Vendale decided to take it. Obenreizer bore little or no part in the discussion, and scarcely spoke.

To Geneva, to Lausanne, along the level margin of the lake to Vevay, so into the winding valley between the spurs of the mountains, and into the valley of the Rhone. The sound of the carriage-wheels, as they rattled on, through the day, through the night, became as the wheels of a great clock, recording the hours. No change of weather varied the journey, after it had hardened into a sullen frost. In a sombre-yellow sky, they saw the Alpine ranges; and they saw enough of snow on nearer and much lower hill-tops and hill-sides, to sully, by contrast, the purity of lake, torrent, and waterfall, and make the villages look discoloured and dirty. But no snow fell, nor was there any snow-drift on the road. The stalking along the valley of more or less of white mist, changing on their hair and dress into icicles, was the only variety between them and the gloomy sky. And still by day, and still by night, the wheels. And still they rolled, in the hearing of one of them, to the burden, altered from the burden of the Rhine: “The time is gone for robbing him alive, and I must murder him.”

They came, at length, to the poor little town of Brieg, at the foot of the Simplon. They came there after dark, but yet could see how dwarfed men’s works and men became with the immense mountains towering over them. Here they must lie for the night; and here was warmth of fire, and lamp, and dinner, and wine, and after-conference resounding, with guides and drivers. No human creature had come across the Pass for four days. The snow above the snow-line was too soft for wheeled carriage, and not hard enough for sledge. There was snow in the sky. There had been snow in the sky for days past, and the marvel was that it had not fallen, and the certainty was that it must fall. No vehicle could cross. The journey might be tried on mules, or it might be tried on foot; but the best guides must be paid danger-price in either case, and that, too, whether they succeeded in taking the two travellers across, or turned for safety and brought them back.

In this discussion, Obenreizer bore no part whatever. He sat silently smoking by the fire until the room was cleared and Vendale referred to him.

“Bah! I am weary of these poor devils and their trade,” he said, in reply. “Always the same story. It is the story of their trade to-day, as it was the story of their trade when I was a ragged boy. What do you and I want? We want a knapsack each, and a mountain-staff each. We want no guide; we should guide him; he would not guide us. We leave our portmanteaus here, and we cross together. We have been on the mountains together before now, and I am mountain-born, and I know this Pass—Pass!—rather High Road!—by heart. We will leave these poor devils, in pity, to trade with others; but they must not delay us to make a pretence of earning money. Which is all they mean.”

Vendale, glad to be quit of the dispute, and to cut the knot: active, adventurous, bent on getting forward, and therefore very susceptible to the last hint: readily assented. Within two hours, they had purchased what they wanted for the expedition, had packed their knapsacks, and lay down to sleep.

At break of day, they found half the town collected in the narrow street to see them depart. The people talked together in groups; the guides and drivers whispered apart, and looked up at the sky; no one wished them a good journey.

As they began the ascent, a gleam of run shone from the otherwise unaltered sky, and for a moment turned the tin spires of the town to silver.

“A good omen!” said Vendale (though it died out while he spoke). “Perhaps our example will open the Pass on this side.”

“No; we shall not be followed,” returned Obenreizer, looking up at the sky and back at the valley. “We shall be alone up yonder.”

ON THE MOUNTAINThe road was fair enough for stout walkers, and the air grew lighter and easier to breathe as the two ascended. But the settled gloom remained as it had remained for days back. Nature seemed to have come to a pause. The sense of hearing, no less than the sense of sight, was troubled by having to wait so long for the change, whatever it might be, that impended. The silence was as palpable and heavy as the lowering clouds—or rather cloud, for there seemed to be but one in all the sky, and that one covering the whole of it.

Although the light was thus dismally shrouded, the prospect was not obscured. Down in the valley of the Rhone behind them, the stream could be traced through all its many windings, oppressively sombre and solemn in its one leaden hue, a colourless waste. Far and high above them, glaciers and suspended avalanches overhung the spots where they must pass, by-and-by; deep and dark below them on their right, were awful precipice and roaring torrent; tremendous mountains arose in every vista. The gigantic landscape, uncheered by a touch of changing light or a solitary ray of sun, was yet terribly distinct in its ferocity. The hearts of two lonely men might shrink a little, if they had to win their way for miles and hours among a legion of silent and motionless men—mere men like themselves—all looking at them with fixed and frowning front. But how much more, when the legion is of Nature’s mightiest works, and the frown may turn to fury in an instant!

As they ascended, the road became gradually more rugged and difficult. But the spirits of Vendale rose as they mounted higher, leaving so much more of the road behind them conquered. Obenreizer spoke little, and held on with a determined purpose. Both, in respect of agility and endurance, were well qualified for the expedition. Whatever the born mountaineer read in the weather-tokens that was illegible to the other, he kept to himself.

“Shall we get across to-day?” asked Vendale.

“No,” replied the other. “You see how much deeper the snow lies here than it lay half a league lower. The higher we mount the deeper the snow will lie. Walking is half wading even now. And the days are so short! If we get as high as the fifth Refuge, and lie to-night at the Hospice, we shall do well.”

“Is there no danger of the weather rising in the night,” asked Vendale, anxiously, “and snowing us up?”

“There is danger enough about us,” said Obenreizer, with a cautious glance onward and upward, “to render silence our best policy. You have heard of the Bridge of the Ganther?”

“I have crossed it once.”

“In the summer?”

“Yes; in the travelling season.”

“Yes; but it is another thing at this season;” with a sneer, as though he were out of temper. “This is not a time of year, or a state of things, on an Alpine Pass, that you gentlemen holiday-travellers know much about.”

“You are my Guide,” said Vendale, good humouredly. “I trust to you.”

“I am your Guide,” said Obenreizer, “and I will guide you to your journey’s end. There is the Bridge before us.”

They had made a turn into a desolate and dismal ravine, where the snow lay deep below them, deep above them, deep on every side. While speaking, Obenreizer stood pointing at the Bridge, and observing Vendale’s face, with a very singular expression on his own.

“If I, as Guide, had sent you over there, in advance, and encouraged you to give a shout or two, you might have brought down upon yourself tons and tons and tons of snow, that would not only have struck you dead, but buried you deep, at a blow.”

“No doubt,” said Vendale.

“No doubt. But that is not what I have to do, as Guide. So pass silently. Or, going as we go, our indiscretion might else crush and bury ME. Let us get on!”

There was a great accumulation of snow on the Bridge;

Comments (0)