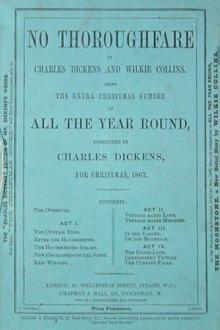

No Thoroughfare by Wilkie Collins (ereader with dictionary .TXT) 📕

"Sally! Hear me, my dear. My entreaty is for no help in the future. It applies to what is past. It is only to be told in two words."

"There! This is worse and worse," cries Sally, "supposing that I understand what two words you mean."

"You do understand. What are the names they have given my poor baby? I ask no more than that. I have read of the customs of the place. He has been christened in the chapel, and registered by some surname in the book. He was received last Monday evening. What have they called him?"

Down upon her knees in the foul mud of the by-way into which they have strayed--an empty street without a thoroughfare giving on the dark gardens of the Hospital--the lady would drop in her passionate entreaty, but that Sally prevents her.

"Don't! Don't! You make me feel as if I was setting myself up to be good. Let me look in your pretty face again. Put yo

Read free book «No Thoroughfare by Wilkie Collins (ereader with dictionary .TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Wilkie Collins

- Performer: -

Read book online «No Thoroughfare by Wilkie Collins (ereader with dictionary .TXT) 📕». Author - Wilkie Collins

“Does it open more than once in the four-and-twenty hours?” asked Obenreizer.

“More than once?” repeated the notary, with great scorn. “You don’t know my good friend, Tick-Tick! He will open the door as often as I ask him. All he wants is his directions, and he gets them here. Look below the dial. Here is a half-circle of steel let into the wall, and here is a hand (called the regulator) that travels round it, just as MY hand chooses. Notice, if you please, that there are figures to guide me on the half-circle of steel. Figure I. means: Open once in the four-and-twenty hours. Figure II. means: Open twice; and so on to the end. I set the regulator every morning, after I have read my letters, and when I know what my day’s work is to be. Would you like to see me set it now? What is to-day? Wednesday. Good! This is the day of our rifle-club; there is little business to do; I grant a half-holiday. No work here to-day, after three o’clock. Let us first put away this portfolio of municipal papers. There! No need to trouble Tick-Tick to open the door until eight tomorrow. Good! I leave the dial-hand at eight; I put back the regulator to I.; I close the door; and closed the door remains, past all opening by anybody, till tomorrow morning at eight.”

Obenreizer’s quickness instantly saw the means by which he might make the clock-lock betray its master’s confidence, and place its master’s papers at his disposal.

“Stop, sir!” he cried, at the moment when the notary was closing the door. “Don’t I see something moving among the boxes—on the floor there?”

(Maitre Voigt turned his back for a moment to look. In that moment, Obenreizer’s ready hand put the regulator on, from the figure “I.” to the figure “II.” Unless the notary looked again at the half-circle of steel, the door would open at eight that evening, as well as at eight next morning, and nobody but Obenreizer would know it.)

“There is nothing!” said Maitre Voigt. Your troubles have shaken your nerves, my son. Some shadow thrown by my taper; or some poor little beetle, who lives among the old lawyer’s secrets, running away from the light. Hark! I hear your fellow-clerk in the office. To work! to work! and build to-day the first step that leads to your new fortunes!”

He good-humouredly pushed Obenreizer out before him; extinguished the taper, with a last fond glance at his clock which passed harmlessly over the regulator beneath; and closed the oaken door.

At three, the office was shut up. The notary and everybody in the notary’s employment, with one exception, went to see the rifle-shooting. Obenreizer had pleaded that he was not in spirits for a public festival. Nobody knew what had become of him. It was believed that he had slipped away for a solitary walk.

The house and offices had been closed but a few minutes, when the door of a shining wardrobe in the notary’s shining room opened, and Obenreizer stopped out. He walked to a window, unclosed the shutters, satisfied himself that he could escape unseen by way of the garden, turned back into the room, and took his place in the notary’s easy-chair. He was locked up in the house, and there were five hours to wait before eight o’clock came.

He wore his way through the five hours: sometimes reading the books and newspapers that lay on the table: sometimes thinking: sometimes walking to and fro. Sunset came on. He closed the window-shutters before he kindled a light. The candle lighted, and the time drawing nearer and nearer, he sat, watch in hand, with his eyes on the oaken door.

At eight, smoothly and softly and silently the door opened.

One after another, he read the names on the outer rows of boxes. No such name as Vendale! He removed the outer row, and looked at the row behind. These were older boxes, and shabbier boxes. The four first that he examined, were inscribed with French and German names. The fifth bore a name which was almost illegible. He brought it out into the room, and examined it closely. There, covered thickly with time-stains and dust, was the name: “Vendale.”

The key hung to the box by a string. He unlocked the box, took out four loose papers that were in it, spread them open on the table, and began to read them. He had not so occupied a minute, when his face fell from its expression of eagerness and avidity, to one of haggard astonishment and disappointment. But, after a little consideration, he copied the papers. He then replaced the papers, replaced the box, closed the door, extinguished the candle, and stole away.

As his murderous and thievish footfall passed out of the garden, the steps of the notary and some one accompanying him stopped at the front door of the house. The lamps were lighted in the little street, and the notary had his door-key in his hand.

“Pray do not pass my house, Mr. Bintrey,” he said. “Do me the honour to come in. It is one of our town half-holidays—our Tir— but my people will be back directly. It is droll that you should ask your way to the Hotel of me. Let us eat and drink before you go there.”

“Thank you; not to-night,” said Bintrey. “Shall I come to you at ten tomorrow?”

“I shall be enchanted, sir, to take so early an opportunity of redressing the wrongs of my injured client,” returned the good notary.

“Yes,” retorted Bintrey; “your injured client is all very well—but- -a word in your ear.”

He whispered to the notary and walked off. When the notary’s housekeeper came home, she found him standing at his door motionless, with the key still in his hand, and the door unopened.

OBENREIZER’S VICTORY

The scene shifts again—to the foot of the Simplon, on the Swiss side.

In one of the dreary rooms of the dreary little inn at Brieg, Mr. Bintrey and Maitre Voigt sat together at a professional council of two. Mr. Bintrey was searching in his despatch-box. Maitre Voigt was looking towards a closed door, painted brown to imitate mahogany, and communicating with an inner room.

“Isn’t it time he was here?” asked the notary, shifting his position, and glancing at a second door at the other end of the room, painted yellow to imitate deal.

“He IS here,” answered Bintrey, after listening for a moment.

The yellow door was opened by a waiter, and Obenreizer walked in.

After greeting Maitre Voigt with a cordiality which appeared to cause the notary no little embarrassment, Obenreizer bowed with grave and distant politeness to Bintrey. “For what reason have I been brought from Neuchatel to the foot of the mountain?” he inquired, taking the seat which the English lawyer had indicated to him.

“You shall be quite satisfied on that head before our interview is over,” returned Bintrey. “For the present, permit me to suggest proceeding at once to business. There has been a correspondence, Mr. Obenreizer, between you and your niece. I am here to represent your niece.”

“In other words, you, a lawyer, are here to represent an infraction of the law.”

“Admirably put!” said Bintrey. “If all the people I have to deal with were only like you, what an easy profession mine would be! I am here to represent an infraction of the law—that is your point of view. I am here to make a compromise between you and your niece— that is my point of view.”

“There must be two parties to a compromise,” rejoined Obenreizer. “I decline, in this case, to be one of them. The law gives me authority to control my niece’s actions, until she comes of age. She is not yet of age; and I claim my authority.”

At this point Maitre attempted to speak. Bintrey silenced him with a compassionate indulgence of tone and manner, as if he was silencing a favourite child.

“No, my worthy friend, not a word. Don’t excite yourself unnecessarily; leave it to me.” He turned, and addressed himself again to Obenreizer. “I can think of nothing comparable to you, Mr. Obenreizer, but granite—and even that wears out in course of time. In the interests of peace and quietness—for the sake of your own dignity—relax a little. If you will only delegate your authority to another person whom I know of, that person may be trusted never to lose sight of your niece, night or day!”

“You are wasting your time and mine,” returned Obenreizer. “If my niece is not rendered up to my authority within one week from this day, I invoke the law. If you resist the law, I take her by force.”

He rose to his feet as he said the last word. Maitre Voigt looked round again towards the brown door which led into the inner room.

“Have some pity on the poor girl,” pleaded Bintrey. “Remember how lately she lost her lover by a dreadful death! Will nothing move you?”

“Nothing.”

Bintrey, in his turn, rose to his feet, and looked at Maitre Voigt. Maitre Voigt’s hand, resting on the table, began to tremble. Maitre Voigt’s eyes remained fixed, as if by irresistible fascination, on the brown door. Obenreizer, suspiciously observing him, looked that way too.

“There is somebody listening in there!” he exclaimed, with a sharp backward glance at Bintrey.

“There are two people listening,” answered Bintrey.

“Who are they?”

“You shall see.”

With this answer, he raised his voice and spoke the next words—the two common words which are on everybody’s lips, at every hour of the day: “Come in!”

The brown door opened. Supported on Marguerite’s arm—his sun-burnt colour gone, his right arm bandaged and clung over his breast— Vendale stood before the murderer, a man risen from the dead.

In the moment of silence that followed, the singing of a caged bird in the courtyard outside was the one sound stirring in the room. Maitre Voigt touched Bintrey, and pointed to Obenreizer. “Look at him!” said the notary, in a whisper.

The shock had paralysed every movement in the villain’s body, but the movement of the blood. His face was like the face of a corpse. The one vestige of colour left in it was a livid purple streak which marked the course of the scar where his victim had wounded him on the cheek and neck. Speechless, breathless, motionless alike in eye and limb, it seemed as if, at the sight of Vendale, the death to which he had doomed Vendale had struck him where he stood.

“Somebody ought to speak to him,” said Maitre Voigt. “Shall I?”

Even at that moment Bintrey persisted in silencing the notary, and in keeping the lead in the proceedings to himself. Checking Maitre Voigt by a gesture, he dismissed Marguerite and Vendale in these words:- “The object of your appearance here is answered,” he said. “If you will withdraw for the present, it may help Mr. Obenreizer to recover himself.”

It did help him. As the two passed through the door and closed it behind them, he drew a deep breath of relief. He looked round him for the chair from which he had risen, and dropped into it.

“Give him time!” pleaded Maitre Voigt.

“No,” said Bintrey. “I don’t know what use he may make of it if I do.” He turned once more to Obenreizer, and went on. “I owe it to myself,” he said—“I don’t admit, mind, that I owe it to you—to account for my appearance in these proceedings, and to state what has been done under my advice, and on my sole responsibility. Can you listen to me?”

“I can listen to you.”

“Recall the time when you started for Switzerland with Mr. Vendale,” Bintrey begin. “You had not left England

Comments (0)