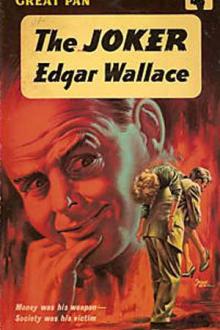

The Joker by Edgar Wallace (best inspirational books .txt) 📕

'I don't know,' said the older man vaguely. 'One could travel... '

'The English people have two ideas of happiness: one comes from travel, one from staying still! Rushing or rusting! I might marry but I don't wish to marry. I might have a great stable of race-horses, but I detest racing. I might yacht--I loathe the sea. Suppose I want a thrill? I do! The art of living is the art of victory. Make a note of that. Where is happiness in cards, horses, golf, women-anything you like? I'll tell you: in beating the best man to it! That's An Americanism. Where is the joy of mountain climbing, of exploration, of scientific discovery? To do better than somebody else--to go farther, to put your foot on the head of the next best.'

He blew a cloud of smoke through the open window and waited until the breeze had torn the misty gossamer into shreds and nothingness.

'When you're a millionaire you either

Read free book «The Joker by Edgar Wallace (best inspirational books .txt) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Edgar Wallace

- Performer: -

Read book online «The Joker by Edgar Wallace (best inspirational books .txt) 📕». Author - Edgar Wallace

nation? It was Ellenbury who bought the ground and gave the orders to the

builders. Nobody knew it was a police station until it was up. After

they’d put in the foundations and got the walls breast-high, there was a

sort of strike because foreign labour was employed, and all the workmen

had to be sent back to Italy or Germany, or wherever they came from.

That’s where Ellenbury’s connection came under notice, though we weren’t

aware that he was working for Harlow till a year later.’

Jim decided upon taking the bolder course, but the lawyer was prepared

for the visitation.

MR ELLENBURY had his home in a large, gaunt house between Norwood and

Anerley. It had been ugly even in the days when square, box-shaped

dwellings testified to the strange mentality of the Victorian architects

and stucco was regarded as an effective and artistic method of covering

bad brickwork. It was in shape a cube, from the low centre of which, on

the side facing the road, ran a long flight of stone steps confined

within a plaster balustrade. It had oblong windows set at regular

intervals on three sides, and was a mansion to which even Venetian blinds

lent an air of distinction.

Royalton House stood squarely in the centre of two acres of land, and

could boast a rosary, a croquet lawn, a kitchen garden, a rustic

summer-house and a dribbling fountain.

Scattered about the grounds there were a number of indelicate statues

representing famous figures of mythology—these had been purchased

cheaply from a local exhibition many years before at a great weeding-out

of those gods chiselled with such anatomical faithfulness that they

constituted an offence to the eye of the Young Person.

In such moments of leisure as his activities allowed, Mr Ellenbury

occupied a room gloomily papered, which was variously styled ‘The Study’,

and ‘The Master’s Room’ by his wife and his domestic staff. It was a high

and ill-proportioned apartment, cold and cheerless in the winter, and was

overcrowded with furniture that did not fit. Round tables and top-heavy

secretaires; a horsehair sofa that ran askew across one corner of the

room, where it could only be reached by removing a heavy card-table;

there was space for Mr Ellenbury to sit and little more.

On this December evening he sat at his roll-top desk, biting his nails

thoughtfully, a look of deep concern on his pinched face. He was a man

who had grown prematurely old in a lifelong struggle to make his

resources keep pace with ambition. He was a lover of horses; not other

people’s horses that show themselves occasionally on a race track, but

horses to keep in one’s own stable, horses that looked over the half-door

at the sound of a familiar voice; horses that might be decked in shiny

harness shoulder to shoulder and draw a glittering phaeton along a

country road.

All men have their dreams; for forty years Mr Ellenbury’s pet dream had

been to drive into the arena of a horse show behind two spanking bays

with nodding heads and high knee action, and to drive out again amidst

the plaudits of the multitude with the ribbons of the first prize

streaming from the bridles of his team. Many a man has dreamt less

worthily.

He had had bad luck with his horses, bad luck with his family. Mrs

Ellenbury was an invalid. No doctor had ever discovered the nature of her

illness. One West End specialist seen her and had advised the calling in

of another. The second specialist had suggested that it would be

advisable to see a third. The third had come and asked questions. Had any

other parents suffered from illusions? Were they hysterical? Didn’t Mrs

Ellenbury think that if she made an effort she could get up from her bed

for, say, half an hour a day?

The truth was that Mrs Ellenbury, having during her life experienced most

of the sensations which are peculiar to womankind, having walked and

worked, directed servants, given little parties, made calls, visited the

theatre, played croquet and tennis, had decided some twenty years ago

that there was nothing quite as comfortable as staying in bed.

So she became an invalid, had a treble subscription at a library and

acquired a very considerable acquaintance with the rottenness of society,

as depicted by authors who were authorities on misunderstood wives.

In a sense Mr Ellenbury was quite content that this condition of affairs

should be as it was. Once he was satisfied that his wife, in whom he had

the most friendly interest, was suffering no pain, he was satisfied to

return to the bachelor life. Every morning and every night (when he

returned home at a reasonable hour) he went into her room and asked: ‘How

are we today?’

‘About the same—certainly no worse.’

‘That’s fine! Is there anything you want?’

‘No, thank you—I have everything.’

This exchange varied slightly from day to day, but generally it followed

on those lines.

Ellenbury had come back late from Ratas after a tiring day. Usually he

directed the Rata Syndicate from his own office; indeed, he had never

before appeared visibly in the operations of the company. But this new

coup of Harlow’s was on so gigantic a scale that he must appear in the

daylight; and his connection with a concern suspected by every reputable

firm in the City must be public property. And that hurt him. He, who had

secretly robbed his clients, who is had engaged in systematic embezzlement

and might now, but for the intervention and help of Mr Stratford Harlow,

have been an inmate of Dartmoor, walked with shame under the stigma of

his known connection with a firm which was openly described as unsavoury.

He was a creature of Harlow, his slave. This sore place in his

self-esteem had never healed. It was his recreation to brood upon the

ignominy of his lot. He hated Harlow with a malignity that none, seeing

his mild, worn face, would suspect.

To him Stratford Harlow was the very incarnation of evil, a devil on

earth who had bound his soul in fetters of brass. And of late he had

embarked upon a novel course of dreaming. It was the confused middle of a

dream, having neither beginning nor end, but it was all about a

humiliated Harlow; Harlow being dragged in chains through the Awful Arch;

Harlow robbed at the apotheosis of his triumph. And always Ellenbury was

there, leering, chuckling, pointing a derisive finger at the man he had

ruined, or else he was flitting by midnight across the Channel with a

suitcase packed with fabulous sums of money that he had filched from his

master.

Mr Ellenbury bit his nails.

Soon money would be flowing into Ratas—he would spend days endorsing

cheques, clearing drafts… drafts…

You may pass a draft into a bank and it becomes a number of figures in a

pass-book. On the other hand, you may hand it across the counter and

receive real money.

Sometimes Harlow preferred that method—dollars into sterling, sterling

into Swiss francs, Swiss francs into florins, until the identity of the

original payment was beyond recognition.

Drafts…

In the room above his head his wife was lying immersed in the

self-revelations of a fictional countess. Mrs Ellenbury had little money

of her own. The house was her property. He could augment her income by

judicious remittances.

Drafts…

Mauve and blue and red. ‘Pay to the order of—’ so many thousand dollars,

or rupees, or yen.

Harlow never interfered. He gave exact instructions as to how the money

was to be dealt with, into which accounts it must be paid and that was

all. At the end of a transaction he threw a thousand or two at his

assistant, as a bone to a dog.

Ellenbury had never been so rich in his life as he was now.

He could meet his bank manager without a sinking feeling in the pit of

his stomach—no longer did the sight of a strange man walking up the

drive to the house fill him with a sense of foreboding. Yet once he had

seen the sheriff’s officer in every stranger.

But he had grown accustomed to prosperity; it had become a normal

condition of life and freed his mind to hate the source of his affluence.

A slave—at best a freedman. If Harlow crooked his finger he must run to

him; if Harlow on a motoring tour wired ‘Meet me at—’ any inaccessible

spot, he must drop his work and hurry there. He, Franklin Ellenbury, an

officer of the High Court of Justice, a graduate of a great university, a

man of sensibility and genius.

No wonder Mr Ellenbury bit at his nails and thought of drafts and sunny

cafes and picture galleries which he had long desired to visit; and

perhaps, after he was sated with the novelty of travel, a villa near

Florence with orange groves and masses of bougainvillaea clustering

between white walls and jade-green jalousies.

‘A gentleman to see you, sir.’

He aroused himself from his dreams with a painful start.

‘To see me?’ The clock on his desk said fifteen minutes after eleven. All

the house save the weary maid was asleep. ‘But at this hour? Who is he?

What does he want?’

‘He’s outside, in a big car.’

Automatically he sprang to his feet and ran out of the room. Harlow! How

like the swine, not condescending to alight, but summoning his Thing to

his chariot wheels! ‘Is that you, Ellenbury?’ The voice that spoke from.

the darkness of the car was his.

‘Yes, Mr Harlow.’

‘You’ll be getting inquiries about the Gibbins woman—probably tomorrow.

Carlton is certain to call—he has found that the letters were posted

from Norwood. Why didn’t you post them in town?’

‘I thought—er—well, I wanted to keep the business away from my office.’

‘You could still have posted them in town. Don’t try to hide up the fact

that you sent those letters. Mrs Gibbins was an old family servant of

yours. You told me once that you had a woman with a similar name in your

employ—’

‘She’s dead—’ began Ellenbury.

‘So much the easier for you to lie!’ was the answer. ‘Is everything going

smoothly at Ratas?’

‘Everything, Mr Harlow.’

‘Good!’

The lawyer stood at the foot of the steps watching the carmine rear light

of the car until it vanished on the road.

That was Harlow! Requesting nothing—just ordering. Saying ‘Let this be

done,’ and never doubting that it would be done.

He went slowly back to his study, dismissed the servant to bed; and until

the early hours of the morning was studying a continental

timetable—Madrid, Munich, Cordova, Bucharest—delightful places all.

As he passed his wife’s bedroom she called him and he went in.

‘I’m not at all well tonight,’ she said fretfully. ‘I can’t sleep.’

He comforted her with words, knowing that at ten o’clock that night she

had eaten a supper that would have satisfied an agricultural labourer.

MR HARLOW had timed his warning well. He had the general’s gift of

foretelling his enemy’s movements.

Jim called the next morning at the lawyer’s office in Theobald’s Road;

and when the dour clerk denied him an interview, he produced his card.

‘Take that to Mr Ellenbury. I think he will see me,’ he said.

The clerk returned in a few seconds and ushered him into a cupboard of a

place which could not have been more than seven feet square. Mr Ellenbury

rose nervously from behind

Comments (0)