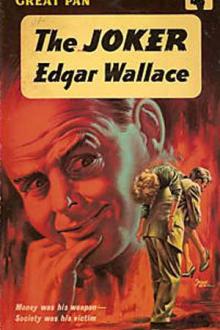

The Joker by Edgar Wallace (best inspirational books .txt) 📕

'I don't know,' said the older man vaguely. 'One could travel... '

'The English people have two ideas of happiness: one comes from travel, one from staying still! Rushing or rusting! I might marry but I don't wish to marry. I might have a great stable of race-horses, but I detest racing. I might yacht--I loathe the sea. Suppose I want a thrill? I do! The art of living is the art of victory. Make a note of that. Where is happiness in cards, horses, golf, women-anything you like? I'll tell you: in beating the best man to it! That's An Americanism. Where is the joy of mountain climbing, of exploration, of scientific discovery? To do better than somebody else--to go farther, to put your foot on the head of the next best.'

He blew a cloud of smoke through the open window and waited until the breeze had torn the misty gossamer into shreds and nothingness.

'When you're a millionaire you either

Read free book «The Joker by Edgar Wallace (best inspirational books .txt) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Edgar Wallace

- Performer: -

Read book online «The Joker by Edgar Wallace (best inspirational books .txt) 📕». Author - Edgar Wallace

hand.

‘Good morning, Inspector,’ he said. ‘We do not get many visitors from

Scotland Yard. May I inquire your business?’

‘I am making inquiries regarding the death of a woman named Gibbins,’

said the visitor.

Mr Ellenbury was not startled. He bowed his head slowly. ‘She was the

woman taken out of the Regent’s Canal some weeks ago; I remember the

inquest,’ he said.

‘Her mother, Louise Gibbins, had been drawing a quarterly pension of

thirteen pounds, which, I understand, was sent by you?’

It was a bluff designed to startle the man into betraying himself but, to

Jim Carlton’s astonishment, Mr Ellenbury lowered his head again.

‘Yes,’ he said, ‘that is perfectly true. I knew her mother, a very

excellent old lady who was for some time in my employ. She was very good

to my dear wife, who is an invalid, and I have made her an allowance for

many years. I did not know she was dead until the case of the drowned

charwoman came into court and caused me to make inquiries.’

‘The allowance was stopped before these facts wire made public,’

challenged Jim Carlton, and again he was dumbfounded when the lawyer

agreed.

‘It was delayed—not stopped,’ he said, ‘and it was only by accident that

the money was not sent at the usual time. Fortunately or unfortunately, I

happened to be rather ill when the allowance should have been sent off.

The day I returned to the office and dispatched the money I learnt of Mrs

Gibbins’s death. It is clear that the woman, instead of informing me of

her mother’s death, suppressed the fact in order that she might benefit

financially. If she had lived and it had come to my notice, I should

naturally have prosecuted her for embezzlement.’

Carlton knew that his visit had been anticipated, and the story cut and

dried in advance. To press any further questions would be to make

Harlow’s suspicion a certainty. He could round off his inquiry plausibly

enough, and this he did.

‘I think that is my final question in the case,’ he said with a smile. ‘I

am sorry to have bothered you, Mr Ellenbury. You never met Miss Annie

Gibbins?’

‘Never,’ replied Ellenbury, with such emphasis that Jim knew he was

speaking the truth. ‘I assure you I had no idea of her existence.’

From one lawyer to another was a natural step: more natural since Mr

Stebbings’ office was in the vicinity, and this interview at least held

one pleasant possibility—he might see Aileen.

She was a little staggered when he entered her room.

‘Mr Stebbings!—why on earth—?’ And then penitently: ‘I’m so sorry! I am

not as inquisitive as I appear!’

Mr Stebbings, who was surprised at nothing, saw him at once and listened

without comment to the detective’s business.

‘I never saw Mr Marling except once,’ he said. ‘He was a wild, rather

erratic individual, and as far as I know, went to the Argentine and did

not return.’

‘You’re sure that he went abroad?’ asked Jim.

Mr Stebbings, being a lawyer, was too cautious a man to be sure of

anything. ‘He took his ticket and presumably sailed; his name was on the

passenger list. Miss Alice Harlow caused inquiries to be made; I think

she was most anxious that Marling’s association with Mr Harlow should be

definitely broken. That, I am afraid, is all I can tell you.’

‘What kind of man was Marling? Yes, I know he was wild and a little

erratic, but was he the type of man who could be dominated by Harlow?’

A very rare smile flitted across the massive face of the lawyer.

‘Is there anybody in the world who would not be dominated by Mr Harlow?’

he asked dryly. ‘I know very little of what is happening outside my own

profession, but from such knowledge as I have acquired I understand that

Mr Harlow is rather a tyrant. I use the word in its original and historic

sense,’ he hastened to add.

Jim made a gentle effort to hear more about Mr Harlow and his earlier

life. He was particularly interested in the will, a copy of which he had

evidently seen at Somerset House, but here the lawyer was adamant. He

hinted that, if the police procured an order from a judge in chambers, or

if they went through some obscure process of law, he would have no

alternative but to reveal all that he knew about his former client;

otherwise—

Aileen was not in her room when he passed through, and he lingered

awhile, hoping to see her, but apparently she was engaged (to her

annoyance, it must be confessed) with the junior partner; he left

Bloomsbury with a feeling that he had not extracted the completest

satisfaction from his visits.

At the corner of Bedford Place a blue Rolls was drawn up by the sidewalk,

and so deep was he in thought that lie would have passed, had not the man

who was sitting at the wheel removed the long cigar from his white teeth

and called him by name. Jim turned with a start. The last person he

expected to meet at this hour of the morning in the prosaic environment

of Theobald’s Road.

‘I thought it was you.’ Mr Harlow’s voice was cheerful, his manner a

pattern of geniality. ‘This is a fortunate meeting.’

‘For which of us?’ smiled Jim, leaning his elbow on the window opening

and looking into the face of the man.

‘For both, I hope. Come inside, and I’ll drive you anywhere you’re going.

I have an invitation to offer and a suggestion to make.’

Jim opened the door and stepped in. Harlow was a skilful driver. He

slipped in and out of the traffic into Bedford Square, and then: ‘Do you

mind if I drive you to my house? Perhaps you can spare the time?’

Jim nodded, wondering what was the proposition. But throughout the drive

Mr Harlow kept up a flow of unimportant small talk, and he said nothing

important until he showed his visitor into the beautiful library. Mr

Harlow threw his heavy coat and cap on to one of the red settees, twisted

a chair round, so that it revolved like a teetotum, and set it down near

his visitor.

‘Somebody followed you here,’ he said. ‘I saw him out of the tail of my

eye. A Scotland Yard man! My dear man, you are very precious to the law.’

He chuckled at this. ‘But I bear you no malice that you do not trust me!

My theory is that it is much better for a dozen innocent men to come

under police surveillance than for a guilty man to escape detection. Only

it is sometimes a little unnerving, the knowledge that I am being

watched. I could stop it at once, of course. The Courier is in the

market—I could buy a newspaper and make your lives very unpleasant

indeed. I could raise a dozen men up in Parliament to ask what the devil

you meant by it. In fact, my dear Carlton, there are so many ways of

breaking you and your immediate superior that I cannot carry them in my

head!’

And Jim had an uncomfortable feeling that this was no vain boast.

‘I really don’t mind,’ Harlow went on; ‘it annoys me a little, but amuses

me more. I am almost above the law! How stupid that sounds!’ He slapped

his knee and his rich laughter filled the room. ‘Of course I am; you know

that! Unless I do something very stupid and so trivial that even the

police can understand that I am breaking the law, you can never touch

me!’

He waited for some comment here, but Jim was content to let his host do

most of the talking. A footman came in at that moment pushing a basket

trolley, and, to Jim’s surprise, it contained a silver tea-service, in

addition to a bottle of whisky, siphon and glasses.

‘I never drink,’ explained Harlow. ‘When I say “never,” it would be

better if I said “rarely.” Tea-drinking is a pernicious habit which I

acquired in my early youth.’ He lifted the bottle. ‘For you—?’

‘Tea also,’ said Jim, and Mr Harlow inclined his head.

‘I thought that was possible,’ he said; and when the servant had gone he

carried his tea back to the writing-table and sat down.

‘You’re a very clever young man,’ he said abruptly, and Jim showed his

teeth in a sceptical smile. ‘I could almost wish you would admit your

genius. I hate that form of modesty which is expressed in

self-depreciation. You’re clever. I have watched your career and have

interested myself in your beginning. If you were an ordinary police

officer I should not bother with you; but you are something different.’

Again he paused, as though he expected a protest, but neither by word nor

gesture did Jim Carlton approve or deny his right to this distinction.

‘As for me, I am a rich man,’ Harlow went on. ‘Yet I need the very help

you can give to me. You are not well off, Mr Carlton? I believe you have

an income of four hundred a year or thereabouts, apart from your salary,

and that is very little for one who sooner or later must feel the need of

a home of his own, a wife and a family—’

Again he paused suggestively, and this time Jim spoke.

‘What do you suggest to remedy this state of affairs? he asked.

Mr Harlow smiled.

‘You are being sarcastic. There is sarcasm in your voice! You feel that

you are superior to the question of money. You can afford to laugh at it.

But, my friend, money is a very serious thing. I offer you five thousand

pounds a year.’

He rose to his feet the better to emphasize the offer, Jim thought.

‘And my duties?’ he said quietly.

Harlow shrugged his big shoulders; and put his hands deep into his

trousers pockets.

‘To watch my interests.’ He almost snapped the words. ‘To employ that

clever brain of yours in furthering my cause, in protecting me when I

go—joking! I love a joke—a practical joke. To see the right man

squirming makes me laugh. Five thousand a year, and all your expenses

paid to the utmost limit. You like play-going? I’ll show you a play that

will set you rolling with joy! What do you say?’

‘No,’ said Jim simply; ‘I’m not keen on jokes.’

‘You’re not?’ Harlow made a little grimace. ‘What a pity! There might be

a million in it for you. I am not trying to induce you to do something

against your principles, but it is a pity.’ It seemed to Jim’s sensitive

ear that there was genuine regret in Harlow’s tone, but he went on

quickly: ‘I appreciate your standpoint. You have no desire to enter my

service. You are, let us say, antipathetic towards me?’

‘I prefer my own work,’ said Jim.

Harlow’s smile was broad and benevolent. ‘There remains only one

suggestion: I want you to come to the dinner and reception I am giving to

the Middle East delegates next Thursday. Regard that as an olive branch!’

Jim smiled. ‘I will gladly accept your invitation, Mr Harlow,’ he said

and then, with scarcely a pause: ‘Where can I find Marling?’

The words were hardly out of his lips before he cursed himself for his

folly. He had not the slightest intention of asking such a fool question,

and he could have kicked himself for the stupid impulse

Comments (0)