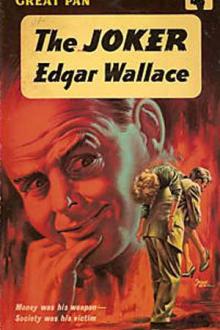

The Joker by Edgar Wallace (best inspirational books .txt) 📕

'I don't know,' said the older man vaguely. 'One could travel... '

'The English people have two ideas of happiness: one comes from travel, one from staying still! Rushing or rusting! I might marry but I don't wish to marry. I might have a great stable of race-horses, but I detest racing. I might yacht--I loathe the sea. Suppose I want a thrill? I do! The art of living is the art of victory. Make a note of that. Where is happiness in cards, horses, golf, women-anything you like? I'll tell you: in beating the best man to it! That's An Americanism. Where is the joy of mountain climbing, of exploration, of scientific discovery? To do better than somebody else--to go farther, to put your foot on the head of the next best.'

He blew a cloud of smoke through the open window and waited until the breeze had torn the misty gossamer into shreds and nothingness.

'When you're a millionaire you either

Read free book «The Joker by Edgar Wallace (best inspirational books .txt) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Edgar Wallace

- Performer: -

Read book online «The Joker by Edgar Wallace (best inspirational books .txt) 📕». Author - Edgar Wallace

fraction of a second, had thrown out of gear the delicate machinery of

investigation.

Not a muscle of Stratford Harlow’s face moved.

‘Marling?’ he repeated. His black brows met in a frown; the pale eyes

surveyed the detective blankly.. ‘Marling?’ he said again. ‘Now where

have I heard that name? You don’t mean the fellow who was my tutor? Good

God! what a question to ask! I have never heard of him from the day he

left for South Africa or somewhere.’

‘The Argentine?’ suggested Jim.

‘Was it the Argentine? I’m not sure. Yes, I am-Pernambuco—cholera—he

died there!’

The underlip came thrusting out. Harlow was passing to the aggressive.

‘The truth is, Marling and I were not very good friends. He treated me

rather as though I were a child, and I cannot think of him without

resentment. Marling! How that word brings back the most uncomfortable

memories! The succession of wretched cottages, of prim, neat gardens, of

his abominable Greek and Latin verses—differential calculi, the whole

horrible gauntlet of so-called education through which a timid youth must

run—and be flayed. Why do you ask?’

Jim had his excuse all ready. He might not recover the ground he had

lost, but he could at least consolidate himself against further

retirement.

‘I have had an inquiry from one of his former associates.’ He mentioned a

name, and here he was on safe ground, for it was the name of a man who

had been a contemporary of Marling’s and who was in the same college. Not

a difficult achievement for Jim, who had spent that morning looking up

old university lists. Evidently it had no significance to Harlow.

‘I seem t remember Marling talking about him.’ he said. ‘But twenty-odd

years is a very long time to cast one’s memory! And very probably I am an

unconscious liar! So far as I know’—he shook his head—‘Marling is dead.

I have no absolute proof of this, but if you wish I will have inquiries

made. The Argentine Government will do almost anything I wish.’

‘You’re a lucky man.’ Jim held out his hand with a laugh.

‘I wonder if I am?’ Harlow looked at him steadfastly. ‘I wonder! And I

wonder if you are, Mr Carlton,’ he added slowly. ‘Or will be!’

Jim Carlton was not in a position to supply an answer. His foot was on

the doorstep when Harlow called him back. ‘I owe you an apology,’ he

said.

Jim supposed that he was talking about the offer he had made, but this

was not the case.

‘It was a crude and degrading business, Mr Carlton—but I have a passion

for experiment. Such methods were efficacious in the days of our

forefathers, and I argued that human nature has not greatly changed.’

Carlton was listening in bewilderment.

‘I don’t quite follow you—’

Mr Harlow showed his teeth in a smile and for a moment his pale eyes lit

up with glee.

‘This was not a case of your following me—but of my following you. A

crude business. I am heartily ashamed of myself!’

Jim was halfway to Scotland Yard before the solution of this mysterious

apology occurred to him. Stratford Harlow was expressing his regret for

the attack that had been delivered by his agents in Long Acre.

Jim stopped to scratch his head.

That man worries me!’ he said aloud.

THE NEWS that Mr Stratford Harlow was entertaining the Middle East

delegates at his house in Park Lane was not of such vital importance that

it deserved any great attention from the London press. A three-line

paragraph at the foot of a column confirmed the date and die hour. For

Jim this proved to be unnecessary, since a reminder came by the second

post on the following day, requesting the pleasure of his company at the

reception.

‘They might have asked me to the dinner,’ said Elk. ‘Especially as it’s

free. I’ll bet that bird keeps a good brand of cigar.’

‘Write and ask for a box; you’ll get it,’ said Jim, and Elk sniffed.

‘That’d be against the best interests of the service,’ he said

virtuously. ‘Do you think I’d get ‘em if I mentioned your name?’

‘You’d get the whole Havana crop,’ said Jim. ‘I’ve got a pick. Anyway,

there’ll be plenty of cigars for you on the night of the reception.’

‘Me?’ Elk brightened visibly. ‘He didn’t send me an invite.’

‘Nevertheless you are going,’ said Jim definitely. ‘I’m anxious to know

just what this reception is all about. I suppose it’s a wonderful thing

to stop these brigands from shooting at one another, but I can’t see the

excuse for a full-scale London party.’

‘Maybe he’s got a girl he wants to show off,’ suggested Elk helpfully.

‘You’ve got a deplorable mind,’ was Jim’s only comment.

He was not the only hard-worked man in London that week. Every night he

walked with Elk and stood opposite the new Rata building in Moorgate

Street. Each room was brilliantly illuminated; messengers came and went;

and he learnt from one of the extra staff whom he had put into the

building, that even Ellenbury, who usually did not allow himself to be

identified publicly with the business, was working till three o’clock

every morning.

Scotland Yard has many agencies throughout the world, and from these the

full extent of Rata’s activities began dimly to be seen.

‘They’ve sold nothing, but they’re going to sell’, reported Jim to his

chief at the Yard; ‘and it’s going to be the biggest bear movement that

we have seen in our generation.’

His chief was a natural enemy to the superlatives of youth.

‘If it were an offence to “bear” the market I should have no neighbours,’

he said icily. ‘Almost every stockbroker I know has taken a flutter at

some time or other. My information is that the market is firm and

healthy. If Harlow is really behind this coup, then he looks like losing

money. Why don’t you see him and ask him plainly what is the big idea?’

Jim made a face.

‘I shall see him tonight at the party,’ he said, ‘but I doubt very much

whether I shall have a chance of worming my way into his confidence!’

Elk was not a society man. It was his dismal claim, that not in any rank

of the Metropolitan Police Force was there a man with less education than

himself. Year after year, with painful regularity, he had failed to pass

the examination which was necessary for promotion to the rank of

inspector.

History floored him; dates of royal accessions and expedient

assassinations drove him to despair. Sheer merit eventually secured him

the rank which his lack of book learning denied him.

‘How’ll I do?’

He had come up to Jim’s room arrayed for the reception, and now he turned

solemnly on his feet to reveal the unusual splendour of evening dress.

The tail coat was creased, the trousers had been treated by an amateur

cleaner, for they reeked of petrol, and the shirt was soft and yellow

with age. ‘It’s the white weskit that worries me,’ he complained. ‘They

tell me you only wear white weskits for weddin’s. But I’m sure the

party’s goin’ to be a fancy one. You wearin’ a white weskit?’

‘I shall probably wear one,’ said Jim soothingly. ‘And you look a peach,

Elk!’

‘They’ll take me for a waiter, but I’m used to that,’ said Elk. ‘Last

time I went to a party they made me serve the drinks. Quite a lot never

got by!’

‘I want you to fix a place where I can find you,’ said Jim, struggling

with his tail coat. ‘That may be very necessary.’

‘The bar,’ said Elk laconically. ‘If it’s called a buf-fit, then I’ll be

at the buf-fit!’

There was a small crowd gathered before the door of Harlow’s house. They

left a clear lane to the striped awning beneath which the guests passed

into the flower-decked vestibule. For the first time Jim saw the

millionaire’s full domestic staff. A man took his card and did not

question the presence of Elk, who strolled nonchalantly past the

guardian.

‘White weskits!’ he hissed. ‘I knew it would be fancy!’

The wide doors of the library were thrown open and here Mr Harlow was

receiving his guests. Dinner was over and the privileged guests were

standing in a half-circle about him.

‘White weskit,’ murmured Elk, ‘and the bar’s in the corner of the room.’

Harlow had already seen them; and although Mr Elk was an uninvited guest,

he greeted him with warmth. To his companion he gave a warm and hearty

hand.

‘Have you seen Sir Joseph?’ he asked.

Jim had seen the Foreign Secretary that afternoon to learn whether he had

made any fresh plans, but had found that Sir Joseph was adhering to his

original intention of attending the reception only. He was telling Harlow

this when there was a stir at the door and, looking around, he saw the

Foreign Secretary enter the room and stop to shake hands with a friend at

the door. He wore his black velvet jacket, his long black he straggled

artistically over his white shirt front. Sir Joseph had been pilloried as

the worst-dressed man in London and yet, for all his slovenliness of

attire, he had the distinctive air of a grand gentleman.

He fixed his horn-rims and favoured Jim with a friendly smile as he made

his way to his host. ‘I was afraid I could not come,’ he said in his

husky voice. ‘The truth is, some foolish newspaper had been giving

prominence to a ridiculous story that went the rounds a few weeks ago;

and I had to be in my place to answer a question.’

‘Rather late for question time, Sir Joseph,’ smiled Harlow. ‘I always

thought they were taken before the real business of Parliament began.’

Sir Joseph nodded in his jerky way.

‘Yes, yes,’ he said, a little testily, ‘but when questions of policy

arise, and a member gives me private notice of his intention of asking

such a question, it can be put at any period.’

He swept Parliament and vexatious questioners out of existence with a

gesture of his hand.

Jim watched the two men talking together. They were in a deep and earnest

conversation, and he gathered from Sir Joseph’s gesticulations that the

Minister was feeling very strongly on the subject under discussion.

Presently they strolled through the crowded library into the vestibule,

and after a decent interval Jim went on their trail. He signalled his

companion from the buffet and Mr Elk, wiping his moustache hurriedly,

joined him as he reached the door.

The guests were still arriving; the vestibule was crowded and progress

was slow. Presently a side door in the hall opened, and over the heads of

the crush he saw Sir Joseph and Mr Harlow come out and make for the

street. Harlow turned back and met the detectives.

‘A short visit,’ he said, ‘but worth while!’ Jim reached the steps in

time to see the Foreign Minister’s car moving into Park Lane and he had a

glimpse of Sir Joseph as he waved his hand in farewell…

‘He stayed long enough to justify a paragraph in the evening

newspaper—and the uncharitable will believe that this was all I wanted!

You’re not going?’

It was Harlow speaking.

‘I am sorry, I also have an engagement—in the House! said Jim

good-humouredly; and Mr Harlow laughed.

‘I see. You were here on duty as well, eh?

Comments (0)